BRITAIN | Anglican Leader's Slavery Past Intensifies UK Reparations Debate

MONTEGO BAY, Jamaica, October 26, 2024 - As Britain grapples with its colonial legacy, a startling revelation from the Archbishop of Canterbury has thrust the reparations debate into sharp focus, even as the UK government maintains its rigid stance against formal apologies for slavery.

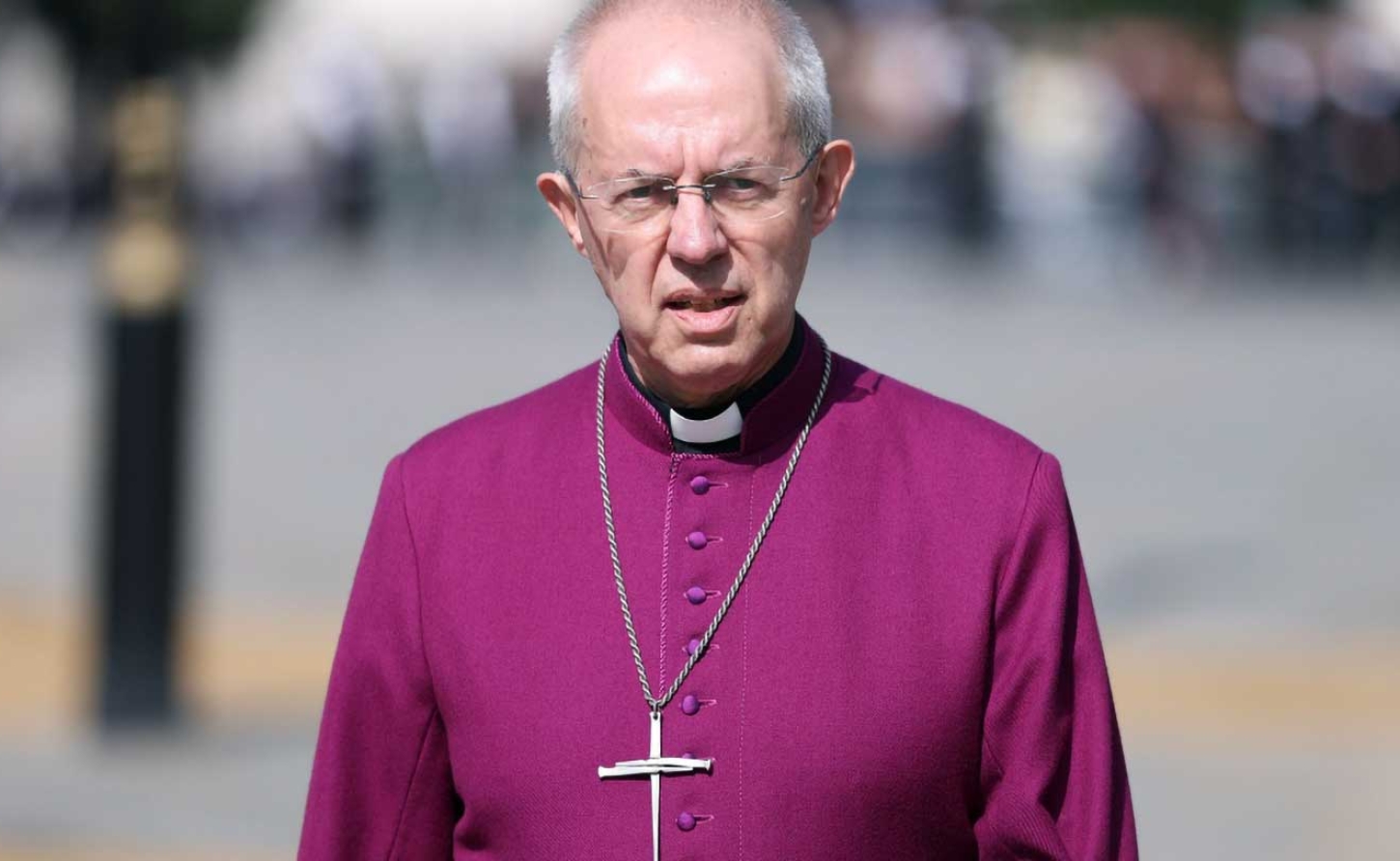

Justin Welby, the spiritual head of the global Anglican communion, has disclosed that his ancestral lineage is directly linked to Jamaica's plantation economy, adding a deeply personal dimension to the Church of England's ongoing reconciliation efforts.

The revelation comes at a particularly charged moment, with British Prime Minister Keir Starmer steadfastly refusing to entertain discussions of reparations at the recent Commonwealth Heads of Government Conference in Samoa, despite growing pressure from the 56-member body.

Welby's disclosure centers on his late biological father, Sir Anthony Montague Browne—Winston Churchill's former private secretary—whose family benefited directly from the enslavement of people in Jamaica and Tobago. The connection traces back to Sir James Fergusson, Browne's great-great-grandfather, who owned the Rozelle plantation in St. Thomas, Jamaica.

The archbishop's ancestor was among those who received compensation when slavery was abolished—part of a £20 million government payout to slave owners. Records from the Centre for the Study of the Legacies of British Slavery indicate that the Rozelle plantation, which held approximately 200 enslaved individuals, earned the Fergusson family £3,591 in 1836—equivalent to more than £3 million in today's currency.

The discovery adds weight to Welby's ongoing efforts to address the Church's historical complicity in slavery. Last year, the Church of England acknowledged that its £9 billion endowment fund was partially built on proceeds from transatlantic slavery through Queen Anne's Bounty, established in 1704.

"I am deeply sorry for these links," Welby had stated at the time. "It is now time to take action to address our shameful past."

The Church has since committed £100 million toward addressing slavery's legacy, though an oversight group led by Bishop Rosemarie Mallett has pushed for an expansion to £1 billion through co-investment initiatives.

During a July visit to Jamaica, where he received an honorary degree from the University of the West Indies, Welby offered an unequivocal apology: "I cannot speak for the government of the United Kingdom but I can speak from my own heart and represent what we say now in England. We are deeply, deeply, deeply sorry. We sinned against your ancestors. I would give anything that that can be reversed, but it cannot."

The Archbishop's family history emerged through an unexpected route. In 2016, a DNA test revealed that Sir Anthony Montague Browne was his biological father—a discovery that came three years after Browne's death. Welby, who never had a relationship with Browne, has emphasized that he received no financial benefit from this connection.

The current Fergusson heir, Sir Adam Fergusson, acknowledged the weight of this history: "The archbishop's connection with the family is a surprise to us all. It is sobering that, five or six generations on, very large numbers of us will have links, known and unknown, to this terrible phase of our history."

Some family members have already taken steps toward reconciliation. Alex Renton, another Fergusson descendant and author of "Blood Legacy – Reckoning with a Family's Story of Slavery," has made personal donations to repair initiatives in Britain and the Caribbean. Renton has also established the Heirs of Slavery group, which encourages families enriched by slavery to acknowledge their past and support reparations campaigns.

As the Church of England continues its "thorough and accurate research programme" into its slavery links, the contrast between its approach and the government's stance becomes increasingly stark. While religious leaders confront their institution's past with concrete actions, Downing Street's resistance to engaging with reparatory justice remains unmoved, creating a growing divide in British society's response to its colonial legacy.

-30-

Ar

Ar  En

En