DIASPORA | Erasing the Ancestors: Philadelphia’s Fight to Preserve America’s Only Federal Slavery Memorial

The Trump administration’s removal of slavery exhibits from the President’s House strikes at the heart of historical truth — and the Caribbean diaspora should take notice

By Calvin G. Brown | WiredJa

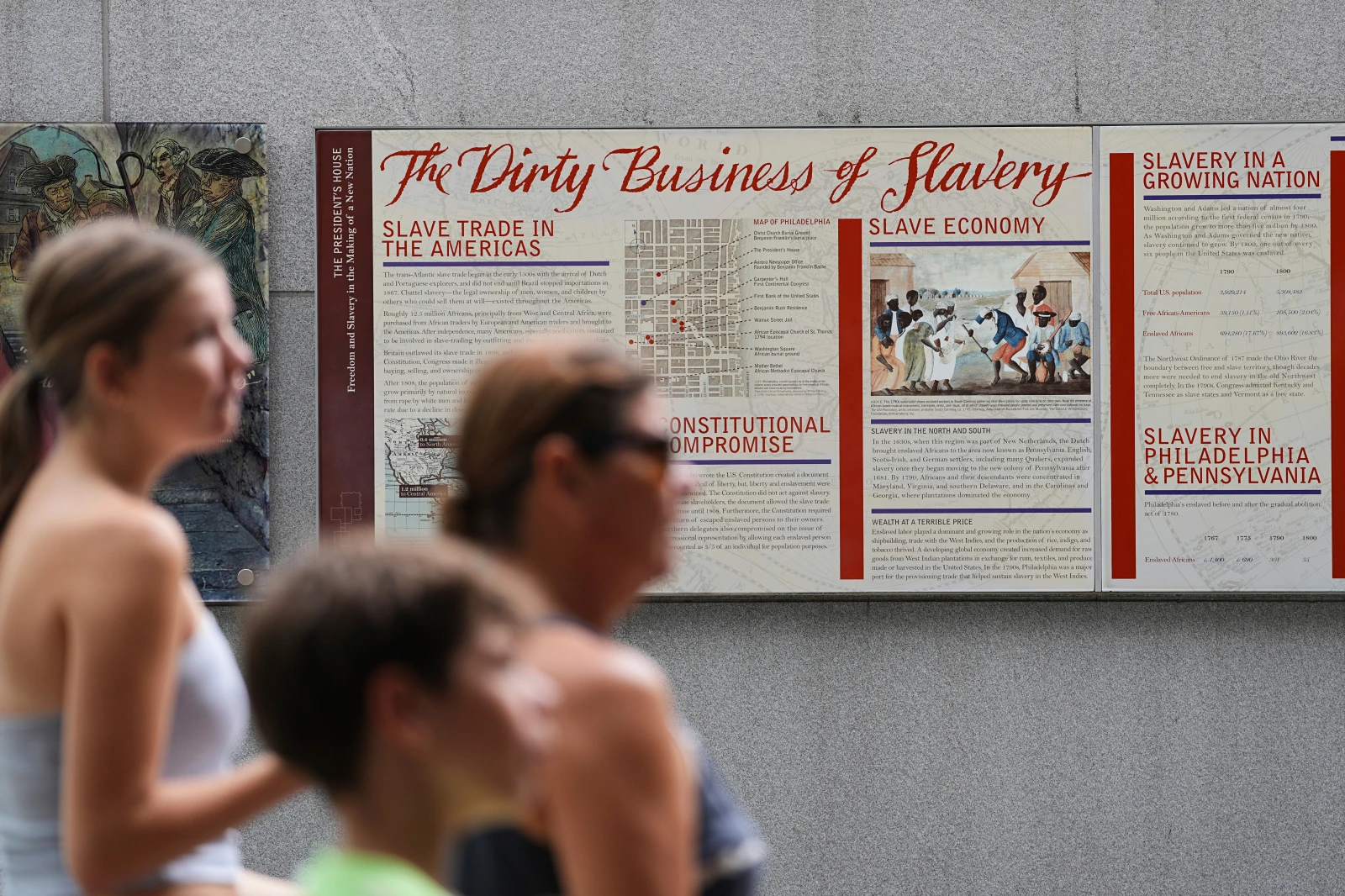

WASHINGTON DC, United States, January 23, 2026 - The crowbars came on a Thursday afternoon. At Independence National Historical Park in Philadelphia — mere steps from where the words “All men are created equal” were first proclaimed — National Park Service workers dismantled the panels telling the stories of nine enslaved human beings who once lived and laboured in George Washington’s presidential household. One woman wept silently as she watched. Someone left a bouquet of flowers. A hand-lettered sign appeared: “Slavery was real.”

By nightfall, only empty bolt holes and shadows remained where the exhibit had stood for fifteen years. But the names of the nine — Austin, Christopher Sheels, Giles, Hercules, Joe Richardson, Moll, Oney Judge, Paris, and Richmond — remain etched in cement at the entrance, a stubborn testament that some truths cannot be pried loose with tools.

The Trump administration dismissed the lawsuit as “frivolous,” claiming it was aimed at “demeaning our brave Founding Fathers who set the brilliant road map for the greatest country in the world.”

But here is what was actually demeaned: the memory of human beings whose unpaid labour built that so-called greatness. And for the millions across the Caribbean and its diaspora whose ancestors endured the same brutality, this erasure is not an abstraction. It is personal.

What Was Lost — The Story of Oney Judge

The President’s House exhibit, which opened in December 2010, was the only memorial on federal property dedicated to commemorating slavery in America. It took twenty years of grassroots struggle — led by the Avenging the Ancestors Coalition under Philadelphia attorney Michael Coard — to force the National Park Service to acknowledge what historians had long documented: that Washington brought enslaved Africans to Philadelphia and deliberately circumvented Pennsylvania law to keep them in bondage.

Pennsylvania’s 1780 Gradual Abolition Act stipulated that enslaved people who remained in the state for six consecutive months could petition for their freedom. Washington’s solution was chillingly methodical: he rotated his human property back to Virginia before the deadline, a scheme he instructed his secretary to accomplish “under pretext that may deceive both them and the Public.”

Among those rotated was Oney Judge, a young woman of mixed heritage who served as Martha Washington’s personal attendant. Born around 1773 at Mount Vernon, Oney was the daughter of an enslaved seamstress and a white English indentured servant. She was, by all accounts, highly skilled and deeply valued — not as a person, but as property.

In the spring of 1796, Oney learned she was to be given away as a wedding gift to Martha Washington’s notoriously ill-tempered granddaughter. She had had enough.

On May 21, 1796, while the President and First Lady ate their evening meal, Oney Judge walked out of the executive mansion and into history. With the help of Philadelphia’s free Black community, she boarded a ship to Portsmouth, New Hampshire, and never returned.

Washington was incensed. He placed advertisements offering rewards for her capture. He dispatched agents to bring her back. He even enlisted a nephew to attempt her seizure years later. Oney refused every overture, telling one of Washington’s emissaries that she preferred poverty and freedom to comfortable enslavement.

She lived the rest of her life in New Hampshire — poor, free, and defiant until her death in 1848. Under the Fugitive Slave Act that Washington himself had signed into law, she remained technically a “runaway” until her final breath.

Her story, and those of the eight others enslaved at the President’s House, is what the Trump administration has now deemed inappropriate for public consumption.

The dismantling at the President’s House did not occur in a vacuum. It is the latest salvo in a systematic campaign to sanitize American history of anything that might complicate the mythology of unblemished greatness.

In March 2025, President Trump signed Executive Order No. 14253, titled “Restoring Truth and Sanity to American History.” The order directs federal agencies to review all interpretive materials and remove content that “inappropriately disparages Americans past or living, including persons living in colonial times.” In its place, the order instructs, materials should “focus on the greatness of the achievements and progress of the American people.”

The order specifically names Independence National Historical Park and sets a deadline of July 4, 2026 — America’s 250th birthday — for completion of the sanitization.

The President’s House was not the first casualty. In September 2025, the administration ordered the removal of an 1863 photograph titled “The Scourged Back” from Fort Pulaski National Monument in Georgia. The image depicts a formerly enslaved man named Gordon, his back a topography of raised scars from savage whippings. It is among the most powerful visual testimonies to slavery’s brutality ever captured.

The administration determined it cast America in a “negative light.”

Philadelphia’s lawsuit argues that the federal government cannot unilaterally dismantle an exhibit created under a binding cooperative agreement. The 2006 pact between the city and the National Park Service explicitly committed to reflecting “all those who lived in the house while it was used as the executive mansion, including the nine enslaved Africans brought by George Washington.”

Governor Josh Shapiro offered a blunter assessment: “Donald Trump will take any opportunity to rewrite and whitewash our history. But he picked the wrong city — and he sure as hell picked the wrong Commonwealth.”

Caribbean Resonance — Our Ancestors, Too

For those of us in the Caribbean and across the diaspora, this fight is not foreign. It is familial.

Oney Judge’s escape echoes the defiance of every maroon who fled to the Cockpit Country, every rebel who rose at Morant Bay, every ancestor who chose death over bondage. Her refusal to return — even when offered conditional freedom, even when facing poverty — is a Caribbean story as much as an American one.

The President’s House was also designated in 1998 as a National Underground Railroad Network to Freedom site, honouring the history of resistance to enslavement through escape and flight. That network did not end at the Mason-Dixon Line. It extended, spiritually and practically, throughout the hemisphere — a web of resistance connecting the enslaved of Philadelphia to the freedom seekers of the entire African diaspora.

When the Trump administration tears down panels documenting this resistance, it is not merely American history being erased. It is ours.

The Caribbean has had its own battles over historical memory — from the removal of Horatio Nelson’s statue in Barbados to ongoing debates about renaming streets and institutions that honour enslavers and colonisers. We understand that how a society remembers its past shapes how it treats its present. We know that erasure is not neutral. It is a choice — a choice that privileges the comfort of the powerful over the truth owed to the descendants of the powerless.

The Truth Remains

The Interior Department called Philadelphia’s lawsuit an attempt to demean the Founding Fathers. But there is nothing demeaning about truth. George Washington commanded armies, presided over a revolution, and helped forge a nation. He also owned human beings, hunted them when they fled, and schemed to keep them enslaved in defiance of state law. Both things are true. A mature nation can hold both.

What is demeaning is the suggestion that American greatness is so fragile it cannot withstand honest accounting. What is demeaning is the implication that the lives of Austin, Christopher Sheels, Giles, Hercules, Joe Richardson, Moll, Oney Judge, Paris, and Richmond are inconvenient footnotes to be discarded when they complicate the narrative.

Michael Coard, whose Avenging the Ancestors Coalition fought for two decades to create the exhibit, has promised “powerful action” in response. The Black Journey, a Philadelphia organisation that conducts walking tours of Black history, has vowed to continue telling the truth regardless of what panels remain standing. “No political action will silence this history,” said the group’s president, Raina Yancey.

She is right. The bolt holes may be empty, but the names remain etched in cement. The stories have been told, written down, passed on. Oney Judge’s escape cannot be un-happened. Hercules’s flight to freedom in 1797 cannot be reversed. The scars on Gordon’s back, photographed in 1863, cannot be un-seen.

History is not a gift bestowed by governments. It is an inheritance claimed by those who refuse to forget.

For the Caribbean and its diaspora, the lesson from Philadelphia is clear: the same forces that would erase the ancestors in America would erase them everywhere. The fight to remember is not their fight alone.

It is ours.

-30-