JAMAICA | A Hero's Betrayal: The Case for Rescinding William Knibb's Order of Merit

Jamaica's Historical Contradiction

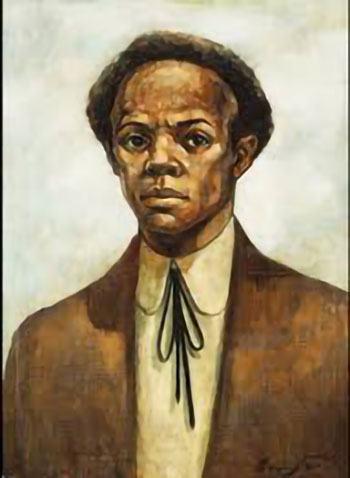

MONTEGO BAY, Jamaica. July 26, 2025 - By Lenworth Fulton with contributions from Calvin G. Brown and Shalman Scott - In 1975, the Michael Manley-led PNP government declared Sam Sharpe a National Hero for leading the 1831-32 Christmas Rebellion which forced the legislative machinery in Britain to bring forward the Emancipation Act which was passed in 1833 and abolished slavery across the British Empire.

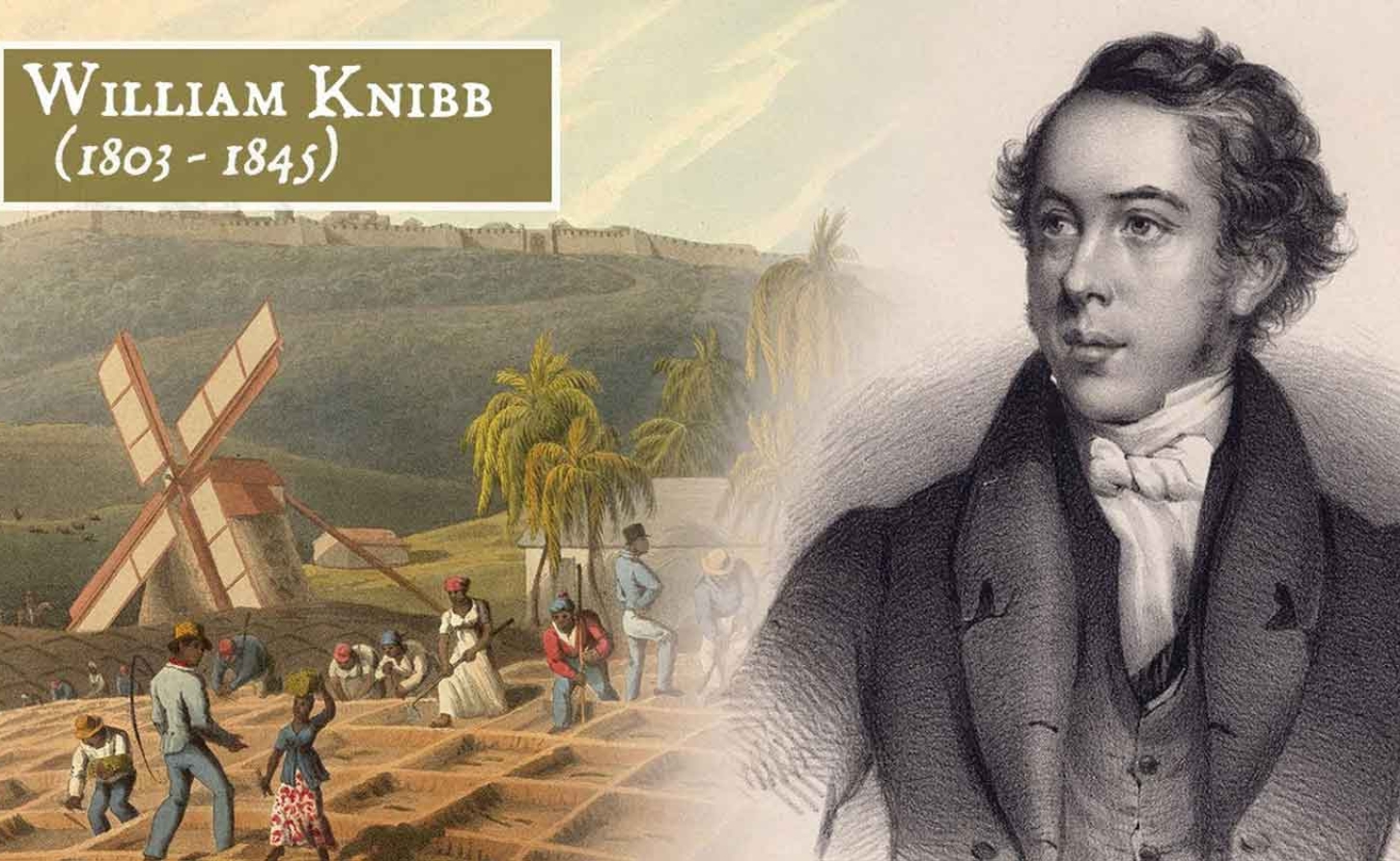

Thirteen years later, in 1988, the Edward Seaga-led JLP government posthumously awarded the Order of Merit—the nation's second-highest honor—to William Knibb, the Baptist missionary whose actions directly contributed to Sharpe's execution.

This glaring contradiction exposes a fundamental flaw in Jamaica's approach to historical memory. How can a nation simultaneously honor a freedom fighter and the man who betrayed him? The answer lies in decades of sanitized colonial historiography that has obscured the true role missionaries played in perpetuating slavery.

Recently uncovered archival evidence, compiled by regional historian Clinton Vane De Brosse Black, historian Shalman Scott, and other scholars "from the bowels of the people," reveals a disturbing pattern of missionary complicity in colonial oppression. At the center of this web of betrayal stands William Knibb, whose carefully constructed legacy as an abolitionist hero crumbles under scrutiny.

The Betrayal Documented

The most damning incident occurred on December 27, 1831, at the dedication of the new Salters Hill Baptist Church, where Knibb clashed bitterly with enslaved congregants over their planned rebellion.

Rather than supporting their quest for freedom, Knibb urged the slaves not to rebel but to "wait on the Lord" and "await Divine Providence." When faced with their determination to act, he allegedly threatened to expel from the church anyone who participated in the impending rebel action. This was spiritual coercion at its most cynical—using religious authority to suppress the very liberation that Christianity should have demanded.

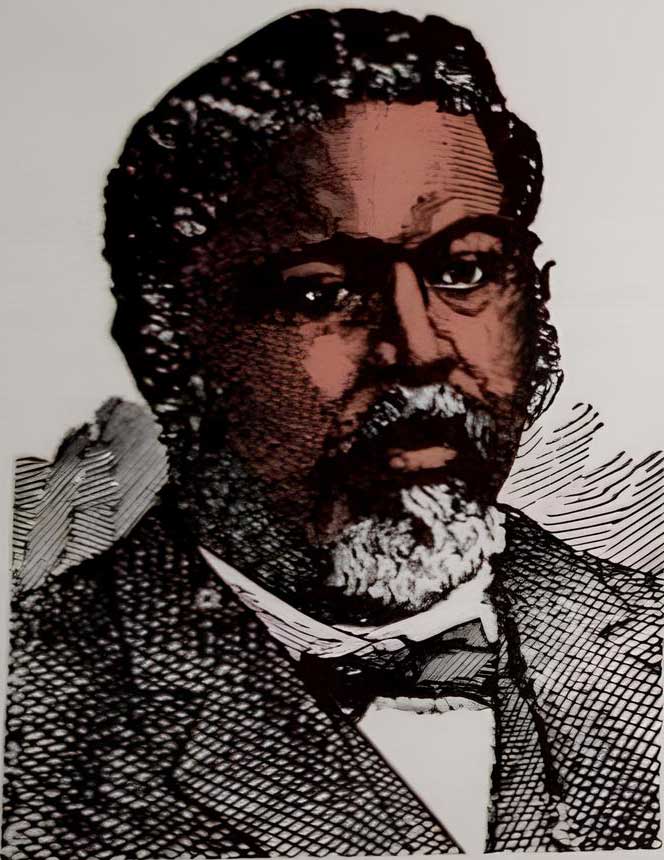

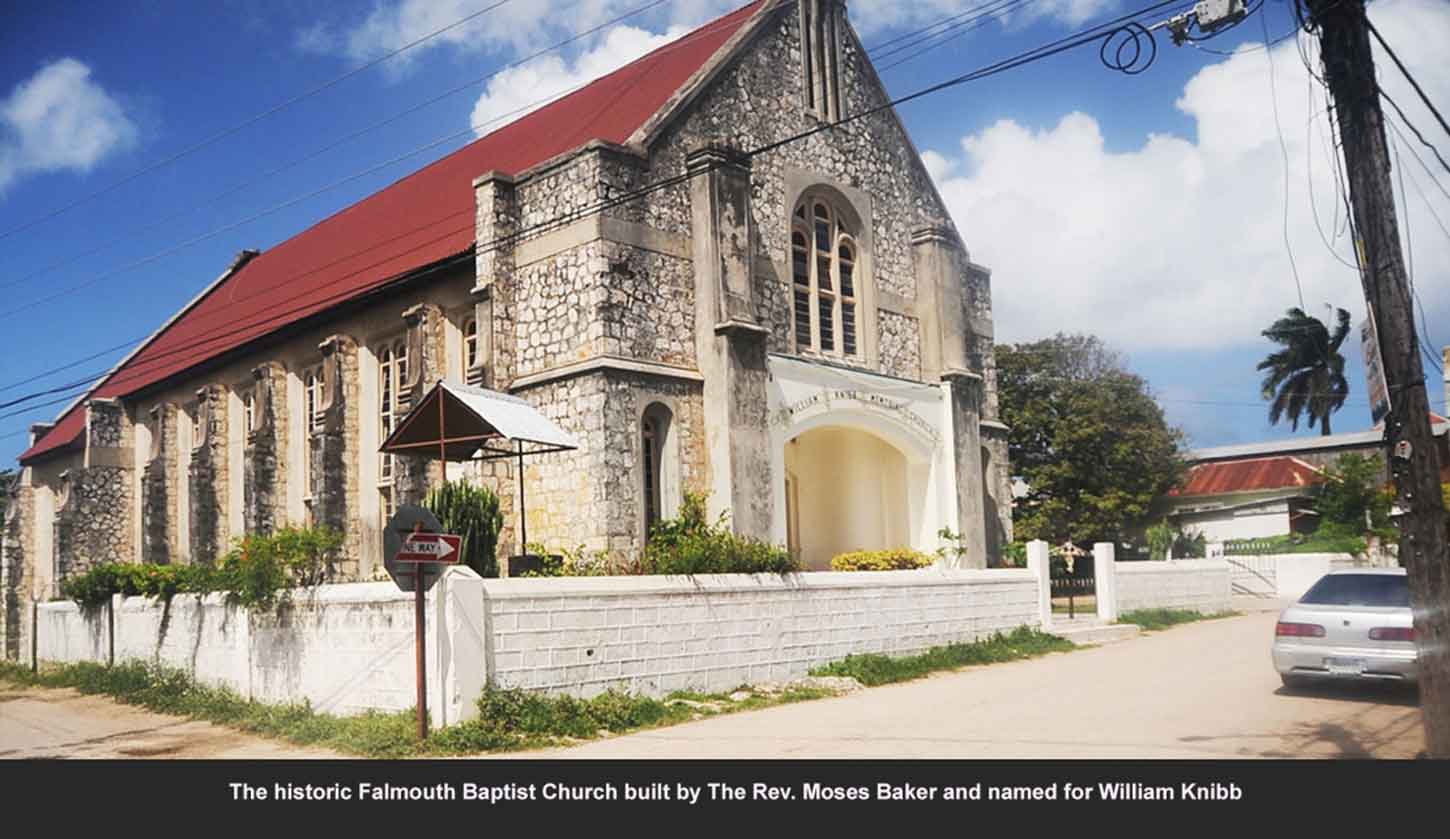

The irony deepens when considering Knibb's position and how he came to hold it. He had begun serving at the Falmouth Baptist Church in 1830, inheriting a congregation of more than 500 souls built by Rev. Moses Baker, a Black Baptist minister who had established the church 41 years earlier. Baker, who arrived in Jamaica from America in 1776 alongside Rev. George Liele, was instrumental in building the Baptist ministry in Western Jamaica.

However, Knibb's presence was not coincidental but the result of a calculated colonial strategy to neutralize Black religious leadership. The Anglican Church's dominance was so complete that other Christian denominations—Baptists, Moravians, Methodists, and Presbyterians—had to receive permission from the Church of England hierarchy, specifically the vestry (forerunner to parish councils), to preach on the island.

Colonial laws passed in 1802 and strengthened in 1810 in response to the 1807 abolition of the slave trade effectively barred Black missionaries like George Liele, Moses Baker, Thomas Swigle, and George Gibbs from continuing their work.

This legal stranglehold forced Baker, broken-hearted on multiple levels—including his son Joseph's abandonment of theological studies in England—to make a desperate request to the British Baptist Missionary Society for white missionaries to "save the work they started here 41 years earlier."

Knibb was essentially a replacement for his older brother Thomas who with the intent to domesticate the radical potential of Black Baptist Christianity, had died after only 14 months in Jamaica. The colonial system had successfully maneuvered to place a white overseer in charge of what had been an indigenous liberation movement.

When the rebellion proceeded despite his opposition, Knibb's response was swift and vindictive. On January 7, 1832—just weeks after Sharpe's rebellion began—he handed over his Falmouth Baptist Church to Major General John Gaynor's St. Ann Militia, transforming the house of worship into a military barracks and prison specifically designed to combat the enslaved revolutionaries. His church was the only Baptist facility used in this manner—a distinction that speaks to his unique level of collaboration.

Economic Motivations Behind Religious Facade

Economic Motivations Behind Religious Facade

Knibb's betrayal was not merely ideological—it was structural and profitable. The colonial system that brought him to Jamaica was designed to ensure that religious authority served plantation interests. While the Anglican Church enjoyed taxpayer financing through the government, creating a state-sponsored religious establishment, non-conformist denominations operated under strict legal controls that effectively eliminated Black leadership.

Far from the selfless missionary portrayed in popular accounts, historical records reveal Knibb as both a product of this system and a beneficiary of it. His 79-acre property at Grumble Pen (later renamed Granville) in Trelawny included horse breeding operations for the local racing industry, demonstrating his integration into the plantation economy he ostensibly opposed.

Working alongside fellow missionary Thomas Burchell, who owned Sandy Bay plantation in Hanover, William Knibb engaged in a sophisticated land speculation scheme. Both men sold their properties to the London Land Bank, controlled by Quakers and Anti-Slavery Society members, while presenting themselves to enslaved congregants as benevolent benefactors creating "freedom villages."

The deception went deeper. After profiting from his secret land deal, Knibb manipulated his Falmouth Baptist Church congregation—including members unaware of his financial arrangements—into gifting him additional land in Duncans, Trelawny. He named this property Kettering, after his English birthplace born in Northamptonshire, in a gesture that symbolically reinforced colonial dominance even as he claimed to champion freedom.

This congregation was part of Moses Baker’s eight thousand members in western Jamaica in 1810 when he appealed for help from the British Baptist Missionary society as he was getting old and the local authorities introduced new amendments to the consolidated slave laws, beginning in 1802, and against Preaching without a licence.

The Reverend John Rowe added a school to the Falmouth Baptist Church in 1814 some 16 years before the Rev. William Knibb arrived there as pastor in 1830, and a full eleven years before Knibb arrived in Jamaica.

Immediately following the Rev. John Rowe, the Rev. Henry Mann pastored the Falmouth Baptist Church.

The Systematic Pattern of Missionary Complicity

Knibb's stance reveals the sophisticated nature of missionary social control. While publicly positioning himself as opposed to slavery in principle, he actively worked to prevent enslaved people from taking concrete action to secure their freedom. This represents the most pernicious form of oppression—using the language of liberation to perpetuate bondage.

His December 27th threats at Salters Hill Baptist Church demonstrate how missionaries weaponized spiritual authority against resistance. By threatening excommunication for those who would fight for freedom, Knibb positioned the church as an instrument of colonial control rather than liberation. The message was clear: divine deliverance would come only through submission to the existing order, not through human agency or struggle for justice.

This theological manipulation was particularly cruel given the context. The colonial system had systematically dismantled Black religious leadership through legal restrictions that required non-Anglican denominations to seek permission from the Church of England to operate. The 1802 and 1810 laws that silenced pioneering Black Baptist ministers were specifically designed to replace indigenous Caribbean Christianity with controllable white oversight.

Moses Baker and George Liele had created a religious framework that inherently supported liberation because it emerged from the enslaved community itself. The colonial authorities recognized this threat and responded by legally mandating that only white missionaries could continue the work. Knibb inherited not just Baker's congregation, but a colonial strategy designed to neutralize Black religious autonomy. His betrayal of the rebellion was not aberrant behavior—it was the system working exactly as designed.

The contrast between Baker's legacy and Knibb's actions represents the difference between authentic liberation theology and colonial religious control. Baker had spent decades building a congregation that would become central to the fight for freedom. The colonial system forced Baker to request his own replacement with someone who would use this spiritual infrastructure to betray the very people Baker had served. When the rebellion proceeded despite his opposition, his subsequent collaboration with colonial authorities appears not as reluctant accommodation but as calculated retaliation against congregants who had defied his authority.

The Aftermath: Mass Murder and Cover-Up

The cover-up was systematic and enduring. Religious services were suspended at Anglican churches as buildings were converted to military barracks and prisons. The Mandeville Anglican Parish Church became a jail where Moravian pastor Rev. Pffifer awaited execution for alleged complicity with the rebels—a fate that notably never befell the truly complicit Knibb.

The Colonial Church Union, led by St. Ann Parish Church rector Rev. G.W. Bridges, coordinated the counter-offensive with plantation owners and local militia. Armed with weapons and attack dogs, they roamed the countryside executing suspected rebels on sight. The brutality was unimaginable, yet it was enabled by the intelligence and facilities provided by collaborating missionaries.

Historical Revision and the 1988 Decision

The 1988 decision to award Knibb the Order of Merit represents a profound failure of historical understanding and moral judgment. Coming just 26 years after independence, this decision suggests that Jamaica's leadership had either failed to examine the historical record critically or chose to perpetuate colonial-era mythmaking.

The award was based on sanitized accounts that deliberately obscured Knibb's role in Sharpe's execution and the broader suppression of the rebellion. These narratives, often written by missionary descendants for English audiences, systematically excluded evidence of betrayal while emphasizing humanitarian rhetoric that bore little resemblance to historical reality.

Consider the cruel irony: Jamaica honors Sam Sharpe as a National Hero for his sacrifice in the cause of freedom, while simultaneously honoring the man whose actions directly contributed to that sacrifice. This contradiction extends beyond historical inaccuracy—it represents a fundamental betrayal of the principles Sharpe died defending.

Beyond Knibb: A Pattern of Historical Amnesia

The Knibb case reveals a broader pattern of historical amnesia that has plagued Jamaica since independence. While European missionaries receive posthumous honors, authentic Caribbean freedom fighters remain marginalized. Paul Bogle, who led the 1865 Morant Bay Rebellion and was hanged in Spanish Town for his Baptist missionary work in the cause of freedom, has never received recognition commensurate with his sacrifice from the Baptist Union that celebrates Knibb.

This selective memory extends to more recent tragedies. The 1980 Eventide Home fire that killed 145 helpless elderly persons in state care, and the 2010 Tivoli incursion that claimed 73 civilian lives without state accountability, demonstrate how patterns of injustice persist when historical wrongs remain unaddressed.

The Scholars' Foundation

Fortunately, Jamaica possesses intellectual leaders who have laid groundwork for historical correction. Professors Rex Nettleford, Orlando Patterson, Richard Hart, and Kamau Brathwaite, alongside Baptist pastors Clement Gayle and Alfred Lane Pugh, have produced scholarship that exposes the sanitized narratives perpetuated by colonial historiography. Historians like Shalman Scott and Clinton Vane De Brosse Black have continued this vital work of archival recovery, uncovering evidence that challenges comfortable myths about the colonial period.

Their collective research reveals how figures like George Liele, Moses Baker, George Gibbs, and Thomas Swigle—Black Baptist preachers who established the faith in Jamaica decades before Knibb's arrival—have been systematically erased from historical memory.

These men, along with countless unnamed freedom fighters, deserve recognition that has been denied while honors flow to their oppressors.

When he came to Jamaica, to replace his brother Thomas, William Knibb studied for a little over a year to become a preacher and was attached to the Fullersfield Baptist Church in Westmoreland before being transferred to the Falmouth Baptist Church.

A Call for Historical Justice

The rescission of William Knibb's Order of Merit would represent more than correcting a single injustice—it would signal Jamaica's commitment to confronting uncomfortable truths about its past. This is not about vilifying Christianity or dismissing all missionary contributions, but about distinguishing between those who served justice and those who served oppression.

The evidence is clear: Knibb betrayed Sam Sharpe and the cause of freedom. He used spiritual authority to suppress rebellion, profited from slavery while presenting himself as an abolitionist, and collaborated with colonial authorities in facilitating mass murder. These actions disqualify him from national honor in any nation that values integrity and justice.

Jamaica's parliament, civil society organizations, and religious leaders must act decisively. The Order of Merit should be rescinded, and the historical record corrected in educational curricula, public monuments, and official documentation. This process should be accompanied by proper recognition for the authentic freedom fighters whose contributions have been obscured by colonial mythology.

Conclusion: Choosing Truth Over Comfort

Sam Sharpe died believing future generations would vindicate his cause. His final words before execution—that he would rather die upon the gallows than live in slavery—represent the moral clarity that should guide Jamaica's approach to historical memory. The choice facing modern Jamaica is stark: perpetuate comfortable lies or embrace difficult truths.

The ancestors who fought for freedom "knew that this day would have come," as the historical record states. They expected their descendants to "clean up the piles of disrespectful, insulting nonsense and lying foolishness masquerading as Jamaican history." Rescinding Knibb's Order of Merit would represent a crucial step in fulfilling that expectation.

In honoring those who betrayed freedom while claiming to champion it, Jamaica dishonors both its heroes and itself. The time has come to choose truth over convenience, justice over mythology. William Knibb's Order of Merit must be rescinded—not in anger, but in service to the historical integrity that a free people deserve.

The dawn of historical honesty awaits. Jamaica need only choose to embrace it.

-30-