JAMAICA | The Forgotten Genius: A Black Man’s Triumph Over the Stars and Slavery

Montego Bay, Jamaica, December 30, 2024 - For over two centuries, the name Francis Williams was buried in the sands of history, obscured by the twin forces of racism and colonialism.

Williams, a Black man born into slavery, rose against unimaginable odds to achieve intellectual heights that were both dazzling and inconvenient for the white supremacist society of his time.

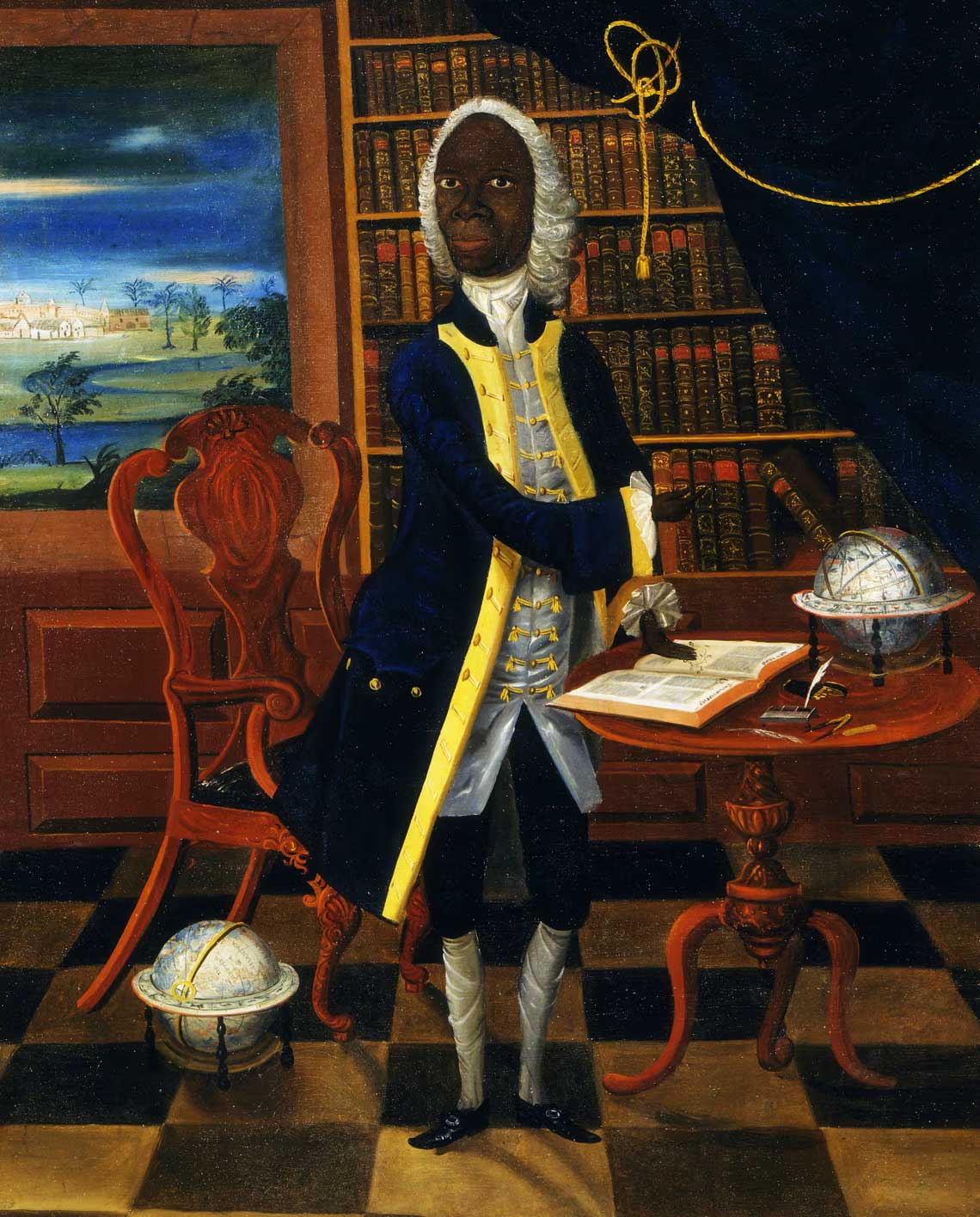

Now, a remarkable analysis of an 18th-century portrait has rewritten his story, shedding light on a groundbreaking scientific achievement: Williams successfully calculated Halley’s comet trajectory over Jamaica in 1759.

This revelation, brought to light by Princeton historian Prof. Fara Dabhoiwala, unravels the painting’s true purpose. Once dismissed as a cruel caricature mocking a Black man’s claim to scholarly status, it is now understood as a proud self-commissioned statement—a defiant proclamation of Williams’ place as a trailblazing intellectual.

Born into bondage, Williams was freed as a child and later achieved feats that contradicted the prevailing narratives of his era: he not only studied Newtonian physics but also mastered it to a degree that vindicated Isaac Newton’s universal laws.

The hidden story is told through the portrait’s intricate details, unearthed using X-ray scans and high-resolution imagery. A celestial scene in the background depicts Halley’s comet streaking across the Jamaican sky in 1759, its path intersecting with constellations precisely as they appeared then.

The book Williams holds bears a meticulously inscribed page number, pointing to a passage in Newton’s Principia on computing comet trajectories. This painting, long relegated to obscurity, now speaks loudly of a Black man’s triumph over both the cosmos and a society determined to deny him recognition.

A Rediscovery of Hidden Genius

The analysis not only reclaims Williams’ legacy but highlights the lengths to which 18th-century colonial societies went to suppress Black excellence. Instruments for mathematical calculations rest on a table in front of Williams, hinting at his groundbreaking work.

Yet his intellect was mocked in print by contemporaries such as Edward Long, a white plantation owner, and historian, and Scottish philosopher David Hume, who dismissed the idea of Black intellectual capacity. These attacks contributed to the widespread belief that the painting must be satirical.

A Trailblazer in Science and Society

Francis Williams’ achievements were nothing short of revolutionary. In an era when colonial powers denied the humanity of enslaved Africans, he calculated the trajectory of Halley’s comet—a feat vindicating Edmond Halley’s 1705 prediction of its return and proving Newton’s universal laws of motion and gravity.

Yet credit for this epochal moment in scientific history was solely attributed to white astronomers.

Williams’ exclusion was not merely an oversight but a deliberate act of systemic racism. Proposed as a fellow of the prestigious Royal Society in 1716—a meeting attended by Newton and Halley themselves—Williams was rejected by a committee on the grounds of his “complexion.” His intellectual contributions, written works, and even personal legacy were dismissed as unworthy of preservation.

Painting the Skies: Halley’s Comet and Newton’s Legacy

At the heart of this rediscovery lies Williams’ connection to the epoch-making return of Halley’s comet in 1759, a moment that captivated the intellectual world.

The comet’s appearance was a dramatic validation of Newtonian physics, which had reshaped humanity’s understanding of the universe.

Williams, residing in Jamaica, not only calculated the comet’s trajectory but also witnessed it firsthand—a rare feat for anyone outside Europe at the time.

Prof. Dabhoiwala’s meticulous work uncovered hidden details that transformed the painting into a scientific testament. X-ray scans of the artwork revealed lines tracing the comet’s luminous path, intersecting with constellations precisely as they would have appeared over Jamaica in 1759.

This celestial choreography, etched into the painting’s background, positions Williams as an active participant in one of history’s greatest scientific confirmations.

The significance of this achievement is amplified by the object in Williams’ hand: an open book with an inscribed page number corresponding to a critical passage in the third edition of Newton’s Principia.

This section explained the mathematical process for calculating cometary trajectories, underscoring Williams’ command of complex astronomical principles. The painting emerges as a defiant declaration: Williams was not merely a witness to scientific history—he was a contributor.

A Legacy Nearly Lost

Despite his towering intellect and accomplishments, Williams lived in a world eager to erase him. By 1759, he had inherited a large Jamaican estate, including plantations and enslaved laborers, from his formerly enslaved African father.

Yet, his contributions to education and science were systematically dismissed. After establishing a school for free Black children, Williams died childless in 1762, leaving no surviving writings to attest to his brilliance.

The erasure of Williams’ legacy was deliberate and systemic. Dabhoiwala points to the racial dynamics of the time, where even groundbreaking achievements by Black intellectuals were deemed unworthy of preservation.

The portrait, later sold by the descendants of Edward Long, symbolized this suppression, its true purpose buried under centuries of misinterpretation.

The Long Arc of Historical Justice

Prof. Fara Dabhoiwala’s findings not only reclaim Francis Williams’ place in history but also illuminate the broader struggle to recognize Black intellectual contributions.

The rediscovery of the painting challenges long-standing narratives that confined Black achievement to the periphery of history. By positioning Williams as a pioneering astronomer, the painting itself becomes a symbol of defiance against the oppressive ideologies of its time.

“This painting is making a really powerful statement,” Dabhoiwala said during a lecture at the Victoria and Albert Museum, where the portrait now resides. “It’s saying: ‘I, Francis Williams, free Black gentleman and scholar, witnessed the most important event in the history of science in our lifetimes, the return of Halley’s comet.

And I calculated its trajectory according to the rules of Newton’s Principia.’” His analysis reframes Williams’ story as one of triumph over an intellectual landscape dominated by white supremacy.

The painting’s background, with its intersecting lines marking constellations and the comet’s luminous arc, is not just an artistic embellishment but a bold assertion of Williams’ mastery. Alongside the celestial tableau, mathematical instruments on the table emphasize his active engagement with the scientific methods of the time. These symbols, hidden for centuries, now speak volumes about a man whose genius transcended the constraints of his era.

A New Legacy for Future Generations

Francis Williams’ story is a testament to the enduring power of historical inquiry. It forces a reckoning with the ways racial bias has shaped the narratives of science and culture.

The rediscovery of his portrait offers a potent reminder that history is not static but can be reexamined to restore the voices of those it sought to silence.

While Williams’ writings have not survived, the revelations about his life and work breathe new life into his legacy. They underscore the importance of recognizing and preserving contributions from marginalized communities, particularly in disciplines like science and the arts.

His achievements, once erased, now serve as an enduring beacon for those who dare to challenge the limits imposed by society.

As we gaze upon Halley’s comet in future centuries, let it not only remind us of the brilliance of Newtonian physics but also of the unyielding spirit of a man who defied his circumstances to chart his own path among the stars.

-30-