Lloyds of London, The Transatlantic Slave Trade, and The Zong Massacre of November 29, 1781

In 1783, the City of London was gripped by a court case which symbolised the brutal economics of slavery. Two years previously, the Liverpool slave ship Zong had set out from Accra, in present-day Ghana, with 442 men, women and children crammed in its hold.

By November 29 1781, according to the crew, navigational errors sent the ship off course. Fearing low water supplies, captain Luke Collingwood made a cold calculation. Over the course of a few days, he threw 132 enslaved people overboard.

Collingwood was able to jettison what he thought of as his valuable “cargo” because the slave ship investors had an insurance policy. When the ship returned to Britain its syndicate of owners, led by Liverpool slave trader William Gregson, lodged a claim, which was challenged by the insurers. The court case that followed was not a murder trial, but an insurance dispute.

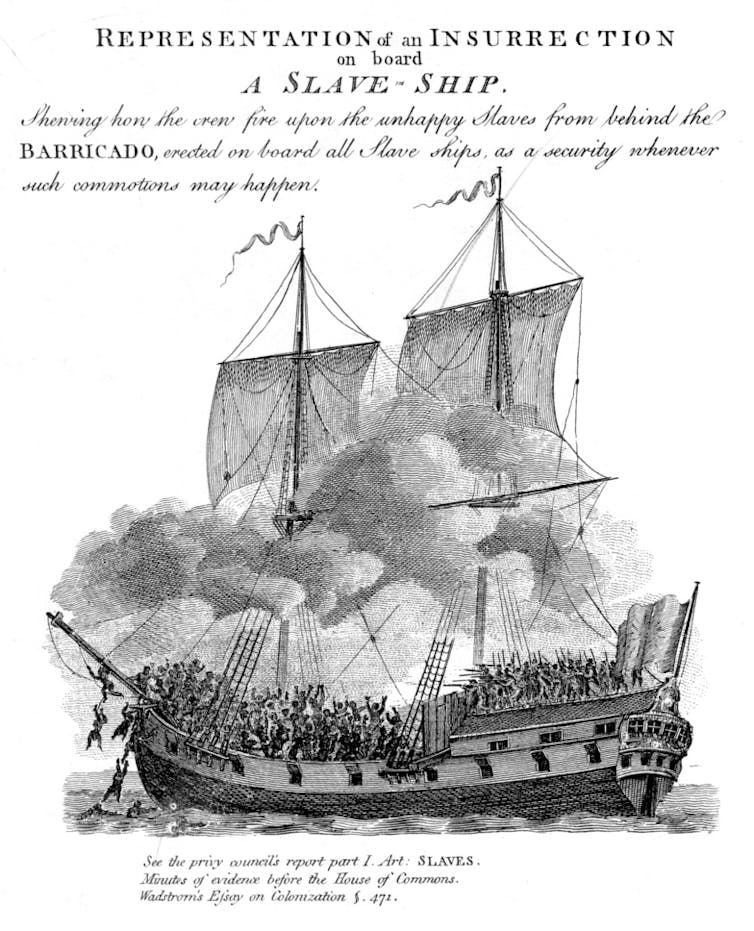

Insurance products were developed for the traders, to mitigate the dangers posed by sea travel, war, piracy and fire. Insurrection, too, was a threat. As many as 10% of slaving voyages experienced uprisings by enslaved people. In Lloyds List, a journal of shipping news, an article dated August 28 1750, details how the Anne of Liverpool was “cut off by the Negroes on the Coast of Guiney – The Captain killed on the Spot, and all the Crew wounded”.

In the wake of the 2020 Black Lives Matter protests, insurance market Lloyds of London apologised for its role in the slave trade and committed to setting up a research project to uncover what its own archives show about these historic links to slavery.

In November 2023, records documenting Lloyds’ involvement in insuring slave voyages were made public.

The research was undertaken by US scholars Alexandre White and Pyar Seth, who are affiliated with the Black Beyond Data research centre. White and Seth received no funding from Lloyds and retained full editorial control over the material. They have housed a digital archive of documents and objects from Lloyds’ collection on a new website, Underwriting Souls.

My work on the Legacies of British Slavery project traced how the profits of slavery were invested in Britain. Research of this kind raises questions about reparations and whether responsibility, today sits with individuals, organisations or the state.

Repairing the past to repair the future

White and Seth estimate that in the 1790s, insurance for the slave economy made up 41% of the broader marine insurance industry. Until 1824, insurance brokers including Lloyds of London, Royal Exchange Assurance and the London Assurance Company held a monopoly on maritime insurance. Lloyds had a dominant market share of between 75% and 90%.

White and Seth have had relatively few artefacts to work with, to examine how slave-trade insurance functioned. This paucity of material reflects the fact that Lloyds was a marketplace and not a company –- individual brokers and underwriters mostly kept their own records.

The few surviving documents include the risk books – insurance agreement ledgers – of two 18th century underwriters, Horatio Clagett and Solomon D’Aguilar. These shed light on the everyday practices and networks that enabled the trade. Enslaved people were insured as “goods”, which the researchers point to as “evidence of the dehumanising commodification and speculation on the financial value of enslaved lives.”

White and Seth digitised the Guipúzcoa insurance agreements, named for the slave ship they related to. This enabled them to analyse how an insurance policy worked.

The agreements fix the value of an enslaved person at £45, which works out at £3,454.25 in today’s money. They also feature a clause unique to slaving voyages: underwriters would cover damage to the ship or any devaluation of enslaved people (including death) due to insurrection.

The policy thus both recognises the human agency of enslaved people in potential insurrection and categorises them as chattel.

John Julius Angerstein, who is known as the “father of Lloyds” and whose art collection formed the basis of the National Gallery, has become a figurehead for institutional connections to slavery. Despite this, concrete evidence of the extent of his connections to the system have proved elusive.

Angerstein was a trustee of a plantation in Grenada and a marine insurance underwriter. It has therefore been assumed that some of his business related to the slave economy. White and Seth’s research places Angerstein in context, providing unequivocal evidence of a network of slave ship captains, West India merchants and slave owners among Lloyds’ subscribers and leading figures.

Nine founding members of Lloyds had ties to slavery. Eleven subscribers received slavery compensation payments, awarded by the government following the abolition of slavery in 1834 for the loss of their human “property”.

Among the digitised objects is a portrait of the former Lloyds chairman and slave holder, Joseph Marryat (1757-1824). In presenting this image White and Seth foreground the stories of enslaved people. Before we meet Marryat, we meet his mixed-heritage illegitimate daughter, Ann, whose mother, Fanny, was enslaved by Marryat. Having been freed by her father when he left Grenada, Ann entered a relationship with a planter by whom she had three children.

Ann, herself, became a slave-holder and received slavery compensation. Her story is an example of the complex choices faced by women of colour within a slave society.

Research I have contributed to documents how instrumental the City of London’s financial organisations were to the slave economy. The inequalities of what historians refer to as “racial capitalism” today – where racism and capitalism intersect – are rooted in this history.

Slavery reparations can take different forms. Historical repair hinges on the idea that acknowledging history can help to redress past silences.

Lloyds has only just begun this process. Research on its more extensive and lucrative activities, providing insurance for slave-produced commodities, has yet to be done.

The company has drawn some criticism for focusing on internal organisational change and targeted corporate investment. Lloyds has described its initiatives as “shaped in consultation with Black experts and diverse colleagues across our market in order to deliver meaningful, sustainable change towards a more inclusive marketplace and society”.

Inevitably there will be calls to go further. The African Union and Caribbean Community recently agreed to press for state-to-state reparations from European nations.

Both paths rely on historical evidence. Research of this kind is vital for reparatory justice.

Katie Donington, Senior Lecturer in Black, Caribbean, and African History, The Open University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.