DIASPORA | From Alligator Alcatraz to Antigua: Inside Trump's Global Deportation Pipeline

The US is building an industrial-scale deportation system — detention infrastructure at home, offloading agreements abroad

By Calvin G. Brown | WiredJa

MONTEGO BAY, Jamaica January 27, 2026 - "We need to get better at treating this like a business — like Amazon Prime, but with human beings." Those words, spoken by Acting ICE Director Todd Lyons at the 2025 Border Security Expo in Phoenix, capture the cold logic driving the most ambitious deportation machinery in American history.

Across the United States, tent cities are rising on military bases. In the Caribbean, small nations are signing agreements to receive deportees who aren't even their citizens.

From Florida's Everglades to Uganda's savannah, a global pipeline is taking shape — one designed to warehouse, process, and export human beings at unprecedented scale.

The bitter irony is this: most of those being fed into the pipeline came to work. Seasonal agricultural labourers picking crops Americans will not touch. Hotel workers making beds Americans refuse to make.

Factory hands on production lines Americans have long abandoned. Many never sought permanent residence — they wanted only to earn, pay their taxes, and return home to families sustained by their remittances. Their labour drove American productivity. Their reward is to be processed like cargo.

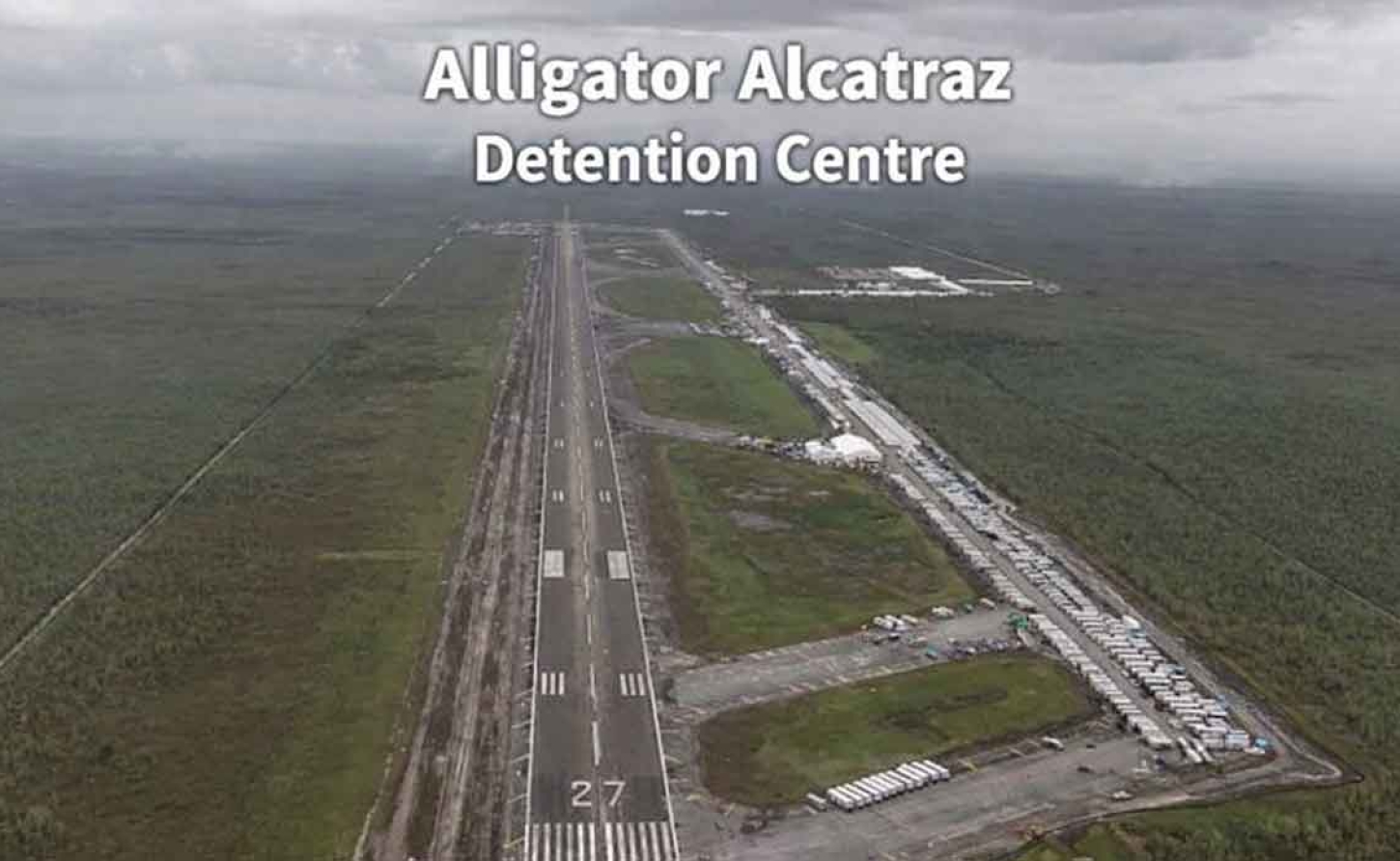

The Domestic Machinery

When Donald Trump returned to the White House in January 2025, approximately 40,000 people sat in immigration detention. By December, that number had surged to nearly 66,000 — the highest level in American history.

Yet this is merely the beginning. Leaked administration plans reveal ambitions to hold 135,000 people at any given time, more than triple the capacity Trump inherited.

The infrastructure buildout has been staggering. In just eleven months, ICE activated 104 new detention facilities — a 91 percent increase.

Congress has authorised $45 billion for detention through Fiscal Year 2029, creating what immigration advocates describe as an "unprecedented growth opportunity" for private prison corporations.

The facilities themselves tell a story of expedience over humanity. At Fort Bliss in Texas, a sprawling tent complex now serves as the nation's largest detention centre.

An internal ICE inspection found conditions violating at least 60 federal standards — inadequate medical care, limited legal access, failure to screen for mental health risks.

The administration has also revived Guantánamo Bay as a detention site and sent migrants to El Salvador's notorious CECOT prison — facilities beyond the reach of American courts and congressional oversight.

The International Offloading Strategy

But detention is only half the equation. The Trump administration has simultaneously constructed a network of international agreements to receive deportees — including people being sent to countries they have never called home.

The Caribbean has emerged as a primary target. Antigua and Barbuda, Dominica, St. Lucia, and St. Kitts and Nevis have all confirmed signed memoranda of understanding with Washington.

Guyana remains in advanced negotiations, with Foreign Secretary Robert Persaud describing talks as "very unique" — linked to the oil-rich nation's estimated skills gap of 80,000 workers amid rapid economic expansion.

The reach extends far beyond the Caribbean. Costa Rica, Ecuador, El Salvador, Panama, Guatemala, Rwanda, Uganda, and South Sudan have all agreed to accept third-country deportees.

Mexico alone has reportedly received more than 6,500 non-nationals. The financial inducements vary wildly — El Salvador received $6 million to detain Venezuelans; Rwanda was reportedly paid $100,000 to accept a single Iraqi man.

The Coercion Playbook

For Caribbean nations, the pressure has been anything but subtle. On December 16, 2025, the Trump administration imposed visa restrictions on Antigua and Barbuda and Dominica, ostensibly over concerns about their Citizenship by Investment programmes.

From January 21, 2026, citizens of both nations must post travel bonds of between $5,000 and $15,000 merely to apply for a US visa.

The timing was not lost on regional observers. Within weeks, both countries had signed deportee agreements.

Former St. Vincent and the Grenadines Prime Minister Ralph Gonsalves, now Opposition Leader, offered a blunt assessment: Caribbean countries are "being picked off one by one" to their detriment.

Washington has simultaneously pressed regional governments to host US Southern Command radar installations — requests meeting fierce resistance from opposition parties and civil society groups.

Antiguan Prime Minister Gaston Browne flatly refused any US military assets on his soil, even as he negotiated the deportee arrangement.

Throughout the region, opposition voices have demanded transparency. In Dominica, United Progressive Party leader Joshua Francis questioned how his country could accept responsibility for deportees "when we have yet to fully address the housing needs of our own people."

In Guyana, the Forward Guyana Movement challenged the government to reveal agreement terms and subject them to parliamentary debate. None has been forthcoming.

The Pipeline's Purpose

Viewed together, the pieces reveal a coherent system. Domestic detention facilities serve as processing centres — holding pens where migrants can be pressured to abandon legal claims or accept voluntary departure.

International agreements provide disposal sites, allowing the US to remove people even when their home countries refuse to accept them.

The human costs are already mounting. The Mixed Migration Centre warns that these frameworks "sidestep key protections," increasing risks that deportees may be sent to places where their safety is endangered.

Integration in receiving countries poses enormous challenges — deportees may not speak local languages, have no community ties, and face limited access to assistance or employment.

For the Caribbean, the implications cut deeper still. Small nations with fragile economies and stretched public services are being asked to absorb populations they did not choose, under terms they cannot fully disclose, in exchange for relief from punitive visa restrictions they did nothing to deserve.

And here the historical echoes grow deafening. Centuries ago, the Middle Passage brought human cargo to these same Caribbean shores — bodies to be exploited for their labour, their humanity reduced to economic units.

Now comes a reverse passage: workers who sustained American agriculture, American hotels, American factories, extracted of their productivity and discarded when politically convenient. Different direction. Same dehumanising logic.

The same powerful nations dictating terms to smaller ones. The same financial transactions for human inventory.

We thought slavery had been abolished. Perhaps it simply changed direction.

The deportation pipeline is open for business. The question now is whether the Caribbean will find its voice before the flow becomes a flood.

-30-