JAMAICA | The Lomé Convention: Jamaica's PJ Patterson and Zambia's Vernon Mwaanga, The Last Two Standing

Of 46 signatories to the historic 1975 Lomé Convention, only two remain alive, while six died by execution. The distance between a conference room and a firing squad was shorter than anyone imagined.

KINGSTON, Jamaica, December 11, 2025 - They are old men now—90 and 80 respectively—and they carry a memory that weighs more than half a century.

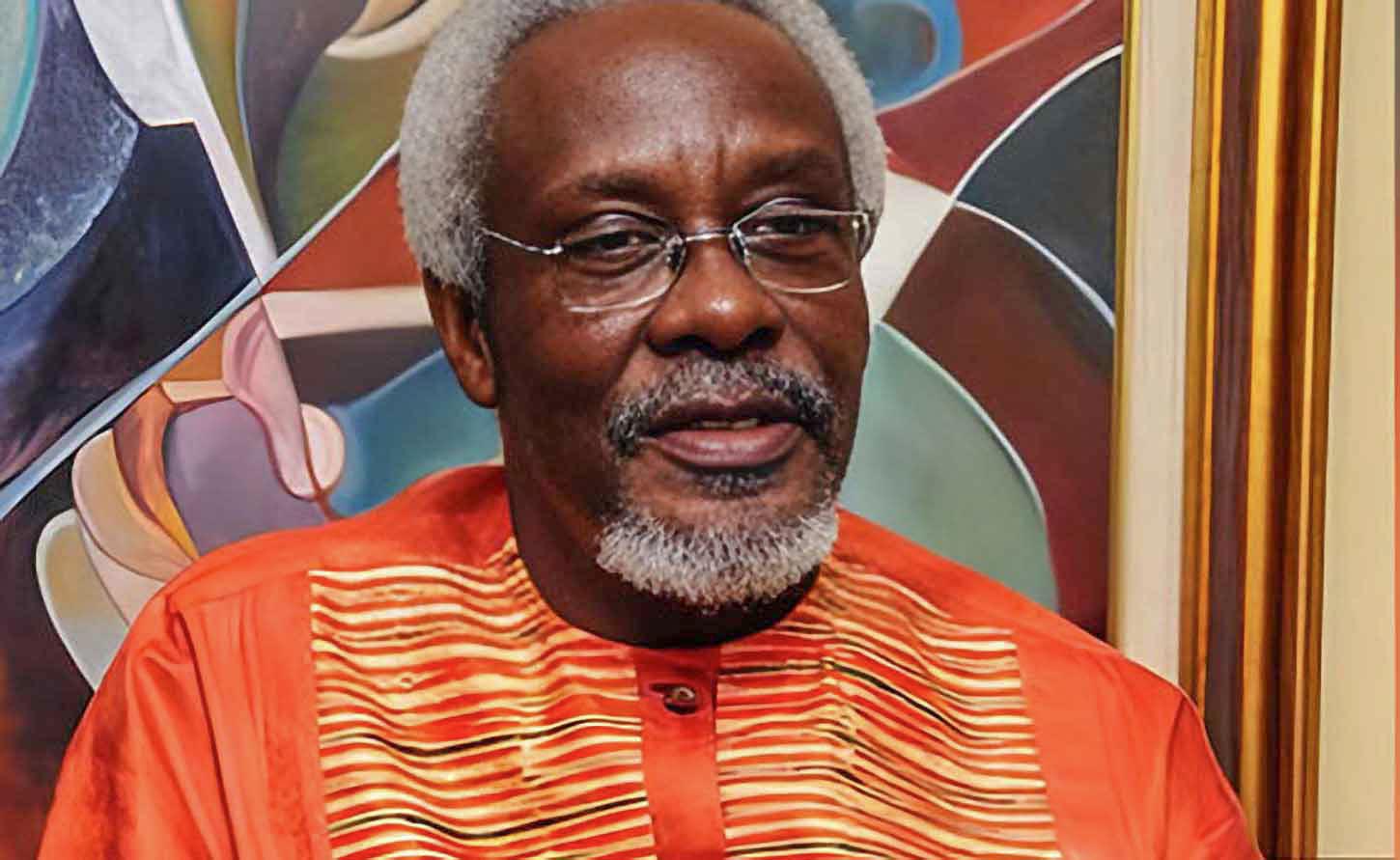

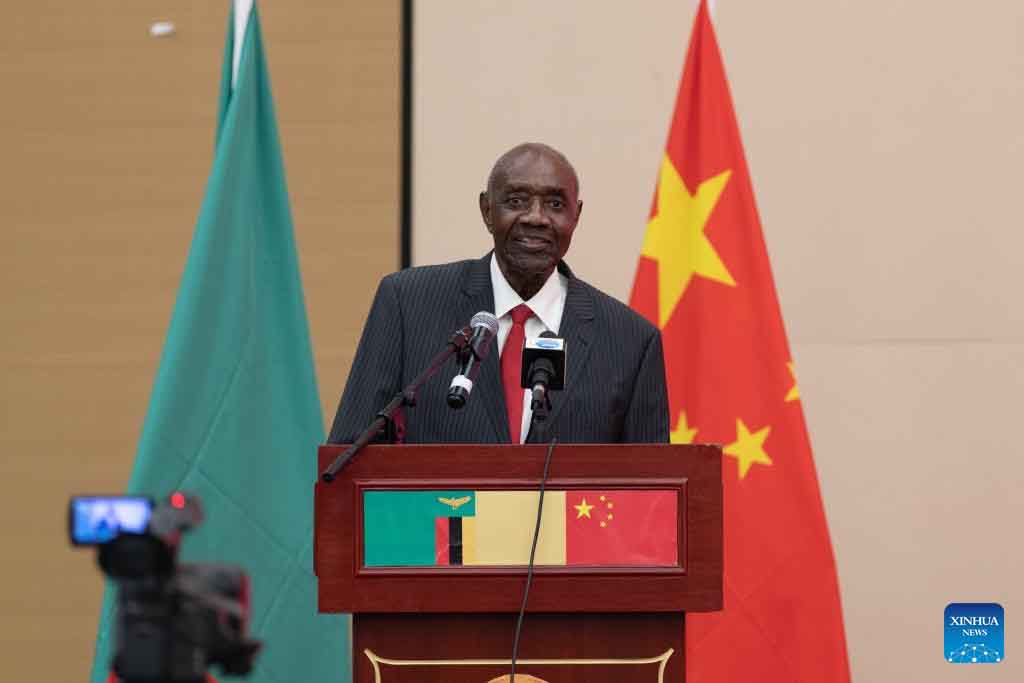

Percival James Patterson in Kingston, Jamaica, and Vernon Johnson Mwaanga in Lusaka, Zambia, are the last living witnesses to a moment when the post-colonial world believed it could reshape global power through signatures and good faith.

On February 28, 1975, in Lomé, Togo, 46 representatives from African, Caribbean, and Pacific nations signed a convention with the European Economic Community that promised a new economic order—trade preferences, aid guarantees, and most importantly, dignity.

The photographs from that day show men in suits and traditional dress, pens poised over documents, faces bright with the optimism of newly independent nations.

What the photographs don't show is what came next: the coups, the firing squads, the beach executions, the political murders disguised as traffic accidents. At least six signatories would meet violent deaths within fifteen years. Some never saw 1980.

Patterson and Mwaanga survived not through luck, but through the accident of geography and system. They signed the same documents as men who would later face bullets, ropes, and unmarked graves.

They shook hands with future corpses. And they alone remain to ask the question that haunts the entire post-colonial project: Why did democracy take root in some soil and drown in blood in others?

What Lomé Promised

The 46 signatories represented countries that had thrown off imperial rule and were now demanding seats at the economic table. They negotiated trade terms, stabilization funds for commodity prices, and protocols that recognized their sovereignty.

Patterson, then Jamaica's Minister of Industry, Tourism and Foreign Trade, chaired the entire ACP ministerial negotiation. He wasn't technically Foreign Minister—Prime Minister Michael Manley held that portfolio—but Patterson was the architect, the deal-maker, the one who forged consensus among nations separated by oceans and political philosophies. At 40, he was already being groomed for leadership.

The signatories were a diverse lot: foreign ministers and finance ministers, ambassadors and planning commissioners, even royalty. Prince Tupouto'a of Tonga signed alongside former revolutionaries and Harvard PhDs. They believed they were planting seeds. Some of those seeds grew into towering careers. Others were burned before they could take root.

Patterson: Democracy's Dividend

To understand why Patterson survived to 90, you have to understand what Jamaica built: a contentious, messy, but fundamentally functional democracy. Patterson rose through elections, not coups.

He lost debates but won ballots. When he finally became Prime Minister in 1992—Jamaica's first dark-skinned Afro-Jamaican to hold the office—it was through constitutional succession, not revolutionary seizure.

His tenure lasted 14 years. Four consecutive election victories. He ended Jamaica's 18-year IMF borrowing relationship, helped establish the Caribbean Court of Justice, and co-architected the CARICOM Single Market.

His opponents called him too cautious, too centrist, too willing to compromise. They never called him a dictator. They never needed to flee the country or fear midnight arrests.

At 90, Patterson remains active. Last month, he was advocating for climate justice before G20 leaders. In November 2025, Prime Minister Andrew Holness tapped him to help coordinate hurricane recovery efforts.

He gives lectures at the PJ Patterson Institute for Africa-Caribbean Advocacy at UWI Mona. He writes op-eds. He survives because the system that elevated him never required him to eliminate rivals—only outvote them.

This is democracy's dividend: you get to grow old.

Mwaanga: The Diplomat Who Endured

His survival strategy was counterintuitive: he left politics. In 1976, Mwaanga entered the private sector, stepping back from the frontlines of Zambian power struggles.

When he returned to government in 1991, it was as Foreign Minister again, then Information Minister across multiple administrations. He learned to be useful without being threatening—advisor without being rival.

At 80, he remains Zambia's elder statesman. In December 2024, he appeared on national television discussing the 2026 elections.

In September, the Chinese ambassador visited him, calling Mwaanga "a witness of China-Zambia friendship." President Hakainde Hichilema consults him regularly. He has outlived most of his generation by understanding that in African politics, survival sometimes requires strategic retreat.

But strategic retreat doesn't explain everyone. Six of his fellow signatories had no time to retreat. The bullets came too fast.

The Executions: Six Who Never Saw History

Ghana's Bullet: Roger Joseph Felli

Roger Joseph Felli was 35 when he signed at Lomé as Ghana's Commissioner for Economic Planning. By 1979, he had risen to Foreign Minister—a trajectory that mirrored Patterson's.

But Ghana in 1979 was not Jamaica. On June 4, Flight Lieutenant Jerry Rawlings and junior officers seized power, overthrowing the government and launching a "house cleaning" revolution against corruption.

On June 26, 1979, Felli faced a firing squad. He was 38 years old. That same day, three former heads of state were executed: General Ignatius Acheampong, General Frederick Akuffo, and General Akwasi Afrifa. The revolution consumed its predecessors in a single morning of gunfire.

From conference tables in Lomé to an execution post in Accra—four years.

Liberia's Beach: David Franklin Neal

David Franklin Neal held degrees from the University of Michigan and the London School of Economics. He was Liberia's Minister of Planning and Economic Affairs, one of the technocrats President William Tolbert relied on to modernize the country. In late 1979, Neal met with President Jimmy Carter in Washington, discussing development strategies and aid packages.

On April 12, 1980, Master Sergeant Samuel Doe led a coup that murdered President Tolbert in his bed. Ten days later, on April 22, thirteen government officials were tied to posts on Barclay Beach in Monrovia. Doe's soldiers opened fire as cameras rolled and crowds cheered. Neal's development plans scattered in the ocean wind. His body fell where the Atlantic meets the sand.

He was among the first to die. Liberia's civil wars would eventually claim 250,000 more.

Malawi's Lie: Dick Matenje

Dick Matenje signed for Malawi as Minister of Finance and Trade. By 1983, he had become Secretary-General of the Malawi Congress Party and a member of the "Mwanza Four"—cabinet members who dared to question President Hastings Banda's absolute rule and the influence of his "official hostess" Cecilia Kadzamira.

On May 18, 1983, Matenje and three colleagues died in what the regime called a "traffic accident." The lie was transparent but effective. Investigations years later revealed the truth: brutal political assassination.

Matenje had been strangled. His body was dumped to simulate a crash. Democracy doesn't die in car accidents—it's murdered and the corpse is arranged to look natural.

Malawi wouldn't hold multiparty elections until 1994, eleven years after Matenje's death.

Sierra Leone's Verdict: Francis Minah

Francis Minah was Trade Minister at Lomé. He later became Vice President under Siaka Stevens before being accused—many say falsely—of plotting against President Joseph Momoh. On October 7, 1989, Minah was executed on treason charges that most international observers considered politically motivated. His real crime was being too competent, too popular, too much of a potential alternative.

Sierra Leone would descend into a decade-long civil war within two years of Minah's execution—one of Africa's bloodiest conflicts. Sometimes executions don't prevent instability. They guarantee it.

Burundi's Coup: Gilles Bimazubute

Gilles Bimazubute was Burundi's Foreign Minister in 1975, a Tutsi who courageously supported democratic majority rule in a country fracturing along ethnic lines. By 1993, he had become Vice President of the National Assembly under President Melchior Ndadaye, Burundi's first democratically elected Hutu president.

On October 21, 1993, Tutsi paratroopers launched a coup. They murdered President Ndadaye and hunted down his allies. Bimazubute was killed that same day. The coup failed but succeeded in plunging Burundi into twelve years of civil war that killed 300,000 people. Bimazubute died for supporting democracy. Burundi's people paid the price.

Mali's Disappeared: Charles Samba Cissokho

Lieutenant Colonel Charles Samba Cissokho was Mali's Foreign Minister in 1975. In 1978, he was arrested during a political purge under President Moussa Traoré. His fate afterward remains officially unknown. No trial. No execution announcement. No grave.

He simply disappeared—absorbed into the machinery of authoritarian rule. Some deaths don't even get the dignity of documentation.

The Pattern: Violence as Policy

Six out of 46 is not a statistical anomaly. It's a pattern. All six were African signatories. None of the Caribbean or Pacific representatives faced execution or assassination.

This isn't about individual bad luck or personal failings. It's about systems—the presence or absence of democratic institutions, constitutional checks, civilian control of militaries, and cultures that resolve political disputes through ballots rather than bullets.

Ghana, Liberia, Malawi, Sierra Leone, Burundi, and Mali all shared a common trajectory: independence followed by authoritarian consolidation, followed by violent power struggles. In these contexts, being a minister wasn't a job—it was a death sentence on installment. Your crime was visibility. Your execution date was whenever the next coup happened.

Compare this to Jamaica and Zambia, both of which had their political crises but maintained some constitutional continuity. Patterson faced opposition but never an executioner. Mwaanga survived by navigating rather than confronting. Their colleagues in Africa often had no such options.

Even those who died peacefully tell the story. Sir Shridath Ramphal, Guyana's Foreign Minister at Lomé, died in August 2024 at age 95, having served fifteen years as Commonwealth Secretary-General and spent his final years representing Guyana at the International Court of Justice.

He died in his bed, his legacy secure. The difference between Ramphal and Felli isn't talent or dedication. It's that Guyana had institutions that didn't require shooting the previous generation to make room for the next.

What Two Men Remember

From 46 to 2 in fifty years. Patterson and Mwaanga are the last men who can tell you what that conference room felt like, what promises were made, what hopes animated that generation of post-colonial leaders.

They watched their fellow signatories rise to presidents and prime ministers, seen them fall to firing squads and assassins, tracked their disappearances into unmarked graves.

They survived because they were Caribbean and southern African respectively—regions that, despite deep flaws, never fully surrendered to the coup-execution cycle that consumed so much of West and Central Africa.

They survived because elections, however flawed, provided off-ramps from power. They survived because their political opponents wanted to defeat them, not disappear them.

The Lomé Convention itself evolved through four iterations before being replaced by the Cotonou Agreement in 2000, then the Samoa Agreement in 2023.

Patterson witnessed the entire arc. He remembers the optimism of 1975 and knows the body count that followed. At 90, still advocating for climate justice and hurricane recovery, he embodies what could have been if more of his generation had been allowed to grow old.

Mwaanga, at 80, continues meeting with presidents and writing political commentary. He is Zambia's living memory—witness to five decades of political transformation that could have killed him a hundred times over.

That it didn't says something about Zambian resilience, but also about the fragility of that survival. One different coup, one miscalculation, and he joins the list of the executed.

Two old men holding a memory too heavy for one generation. They signed for hope. Six died for it. Forty-four are gone by time or violence.

Two remain to tell the story—that in 1975, they believed a signature could change the world. For six of their colleagues, it did. It marked them for death.

Patterson and Mwaanga are the last witnesses to that particular tragedy. When they die—as they will, time being the one coup no one escapes—the memory of what Lomé meant and what it cost will pass from living testimony into history. Until then, they remember. They remember everything. They remember what six never could.

Percival James Patterson is 90 years old and resides in Kingston, Jamaica. Vernon Johnson Mwaanga is 80 and lives in Lusaka, Zambia. They are the only surviving signatories of the February 28, 1975, Lomé Convention between the African, Caribbean and Pacific Group of States and the European Economic Community.

-30-