ACCESS TO JUSTICE: Delroy Chuck's Evolution

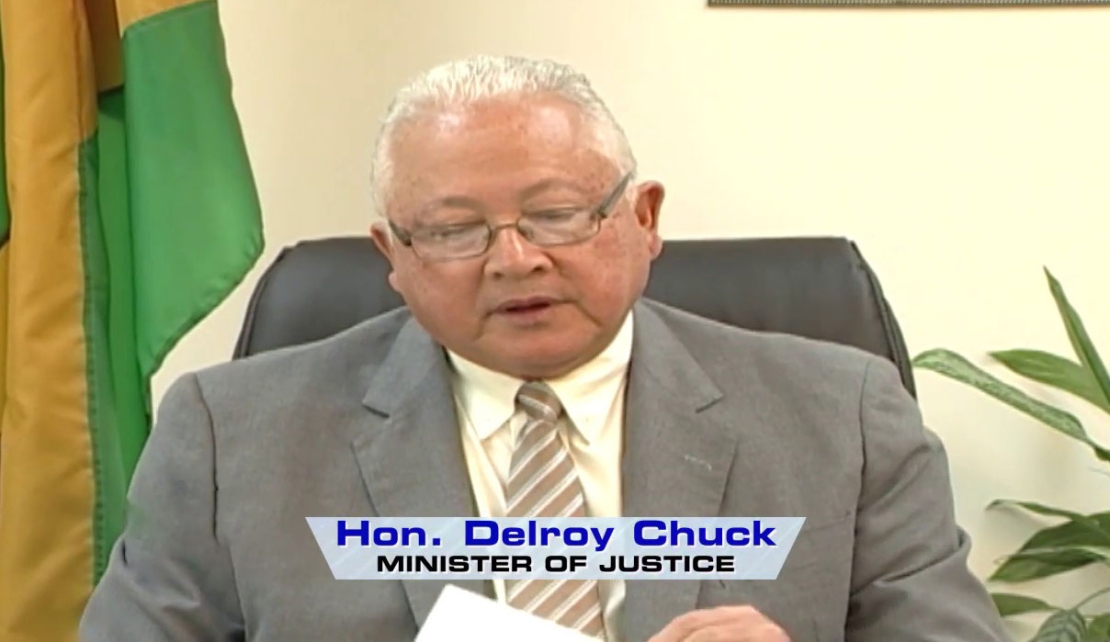

"Access to justice is a very important part for improvement for a better Jamaica"; so Justice Minister Delroy Chuck declared emphatically in an interview reported in The Sunday Gleaner on September 4, last.

It is the kind of declaration that is expected, particularly, from all who have lead responsibility within the justice portfolio anywhere in the democratic world. For, it is public acknowledgement of their primary obligation to the citizenry that they serve.

>

Access to justice is the springboard to the creation of the just society.

It found expression in the storied wisdom of King Solomon in his judgment on motherhood, an innocent mother having been granted access to justice in his presence at the royal court. And the principle has found expression in the creation of an 'Access to Justice Foundation' in present-day Britain.

So, Justice Minister Chuck nailed it in confirming that, within the corridors of government, his mission and stated sacrificial contribution in public office are driven by the bedrock principle of access to justice 'for improvement for a better Jamaica'.

It certainly could not be lost on an entity such as the ministry of consitutional affairs, for example, that access to justice has found expression in a 'Declaration of the United Nations and the Rule of Law', in the following terms:

"Access to justice is a basic principle of the rule of law. In the absence of access to justice, people are unable to have their voice heard, exercise their rights, challenge discrimination or hold decision-makers accountable.

"The Declaration of the High Level Meeting on the Rule of Law emphasizes the right of equal justice for all, including members of vulnerable groups, and reaffirmed the commitment of Member States to taking all necessary steps to provide fair, transparent, effective, non-discriminatory and accountable services that promote access to justice for all".

So, it is universally accepted that any disobedience to the principle embodied in access to justice places a mountain of a stumbling block in the way of efforts to create the just society. What the justice minister is correctly advancing is that such disobedience would remove "a very important part for improvement for a better Jamaica". And, a more just Jamaica is a better Jamaica!

It is, then, the duty of all within the justice portfolio, first and foremost, to seek to discover and recognize any element of 'discrimination' in the provision of access to justice within our system, and 'to take all necessary steps' to have it removed.

And there is an issue which has to be squarely confronted by Minister Chuck: Is he not now precluded from continuing to hold to his repeated position on the landmark question of our final court in the wake of his public affirmation of the power and importance of the principle of access to justice, "for improvement for a better Jamaica"?

Unquestionably, the passing of Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II, recognised by The Gleaner editorial as an "inflection point", cannot but concentrate our minds on Jamaica's relationship with the monarchy whose family members, lest we forget, had been deeply involved in the slave trade..

At Emancipation, Jamaica became, and has remained, adhesively tied to the monarchy at two distinct bonding points: the monarch has been the head of state throughout; and second, an element of the monarch's advisory body has always served as the highest court of Justice.

The Judicial Committee of the Privy Council was created in 1833 as the Great Imperial Court of the British Empire. From its inception, the issue of access to justice obviously loomed large and, for the colonies that would eventually come to attain independent status, an alternative would in time have to be found.

The never-changing challenge of distance had to be faced by all within the far flung realm on which the sun never did set. But, in the case of Jamaica and other former slave plantation territories in the Caribbean, the imperial rulers at once added a defining challenge by creating a societal framework in which only a tiny fraction of persons, former slave owners, were economically enabled to enjoy the privilege of access to justice from their court of last resort.

On both scores, then, distance and affordability, to this day, the vast majority of Jamaicans, most of whom by far are descendants of slaves, could never have enjoyed the benefit of access to justice from their court of last resort. And the sting of denial of access has been exacerbated, including psychologically, by the imposition by the British of visa requirements to enter the United Kingdom.

And so, the leadership of the constitutional affairs ministry will surely rush to seek to extricate our country from the profound humiliation of disparagingly being the only state on the entire planet in which its citizens are required to obtain a visa to enter the land in which their final court of justice and their head of state are housed. It could hardly be doubled that this obligation forms an essential part of the raison d'etre of the ministry..

In relation to our attachment to the final court, there is an internationally endorsed, affordable alternative, the regional Caribbean Court of Justice (CCJ), which has been created for the benefit of Jamaicans, and, from time to time, several senior judges of the Privy Council have publicly exhorted our government to discontinue our use of their services.

In relation to our attachment to the final court, there is an internationally endorsed, affordable alternative, the regional Caribbean Court of Justice (CCJ), which has been created for the benefit of Jamaicans, and, from time to time, several senior judges of the Privy Council have publicly exhorted our government to discontinue our use of their services.

Lamentable, the evidence is that, the leadership of the governing party, without giving any, or any defensible, reason to the citizens, their employers, have decided that things should remain as they have always been. They have voted in the Parliament against Jamaica delinking from the Privy Council to embrace the appellate jurisdiction of the CCJ. And Chuck has himself repeatedly stated that, unless there is "some change", his preference is for a Jamaican final court, and that is but an elusive dream.

The result, then, is that: despite global blessings bestowed upon the structure and operations of the CCJ; despite stirring public admonition from the judges of the Privy Council, and other officials, for us to move on from their court; despite our highest court having declared the correct legislative path to be adopted to accede to the internationally respected alternative CCJ; despite the example of full attachment of some of our regional partners to the CCJ, without any complaint; and more.

Despite the impediments, in place from the beginning and others later imposed, to the enjoyment of the privilege on the part of the vast majority of our citizens; despite the Privy Council dealing with no more than 3 or 4 petitions from Jamaica annually; and despite the game-changing example of the judges of the CCJ coming to our shores to adjudicate on the history-making Shanique Myrie discrimination challenge, the Jamaica Labour Party leadership have refused to recognize the alternative CCJ as a solution to the longstanding lack of access to justice from our final court.

Two matters, must therefore be seriously contemplated if Chuck wishes to be believed and taken seriously in this memorable public declaration that '(A)ccess to justice is a very important part for improvement for a better Jamaica'. First, he has to address his government's faithfulness to Jamaica's commitment to the United Nations Declaration for the Member State to take "all necessary steps to provide fair, transparent, effective, non-discriminatory and accountable services that provide access to justice for all".

And second, the officials in the ministry of constitutional affairs, who have curiously maintained a pregnant silence on this constitutional milestone, should be asked whether the signs of the times are not pointing and ushering them and the government and all elements unto a long sought-after acceptable closure.

At independence sixty years ago in 1962, the right of appeal to Her Majesty was constitutionally enshrined during the reign of Elizabeth II, with the clear consequential implied requirement that a replacement would in time have to be found. An absolutely appropriate alternative has been duly set in place, and Her Late Majesty's monumental reign is no more.

The constitutional affairs ministry should be aware that the area of the main outstanding elements of the reform process that is most easily implementable is delinking from the inaccessible British court provided by the monarch's advisory body, the Privy Council, and for Jamaica to accede to the accessible regional CCJ.

And there is no other element of the reform process from which tangible benefits will immediately flow to the citizens of Jamaica, generations of whom have endured deprivation of that privilege from the time of Emancipation almost 200 years ago. And every day that passes, the unjust denial is extended.

Why, then, not allow that manifestly sparsely used right of appeal to expire along with Her Majesty's reign? The government should not shy away from seizing this fitting, historic moment which cries out for the tabling of the enabling bills to place this link to the monarchy on to its final journey, a link which in truth and in fact really signifies a denial of access to justice.

Moreover, would this not constitute a welcome evolution of Minister Chuck and his colleagues? For, in the end, it is surely duplicitous to resolve to worship at the shrine of the hallowed principle of access to justice and, at the same time, seek to lend support to the generational injustice of having Jamaicans continue clinging to the inaccessible Privy Council.

Let the constitutional affairs ministry therefore urgently move into overdrive so that the scarcely used anachronistic right of appeal to Her Majesty in Council may find a final resting place along with the passing and interment of the longest reigning monarch, Queen Elizabeth II.

AJ NICHOLSON.