JAMAICA | A 20-Year Dance of Delay: The JLP's Stubborn Hesitation on the Caribbean Court of Justice -

MONTEGO BAY, Jamaica, April 16, 2025 - By Calvin G. Brown - As the Caribbean Court of Justice (CCJ) marks its 20th anniversary today, Jamaica stands at a crossroads of its own making—a painful monument to political indecision that has stretched across two decades while five sister nations have moved confidently forward.

The opposition People's National Party demands immediate action, while Prime Minister Andrew Holness and his Jamaica Labour Party continue their elaborate dance of postponement—a waltz of "wait and see" that has now lasted longer than many Jamaicans have been alive. This hesitation has transformed from cautious governance into a peculiar form of postcolonial paralysis.

Time come for full decolonisation." His position resonates with a fundamental truth—how can a nation claim independence while its highest legal decisions retreat to London, where most citizens could never afford to appeal?

"Jamaicans need a final court where they don't need a visa to go there, and where the costs are not way out of their reach," Golding asserts, cutting through the bureaucratic fog that has obscured this debate. "Time come for a Jamaican head of state and the Caribbean Court of Justice as our final court."

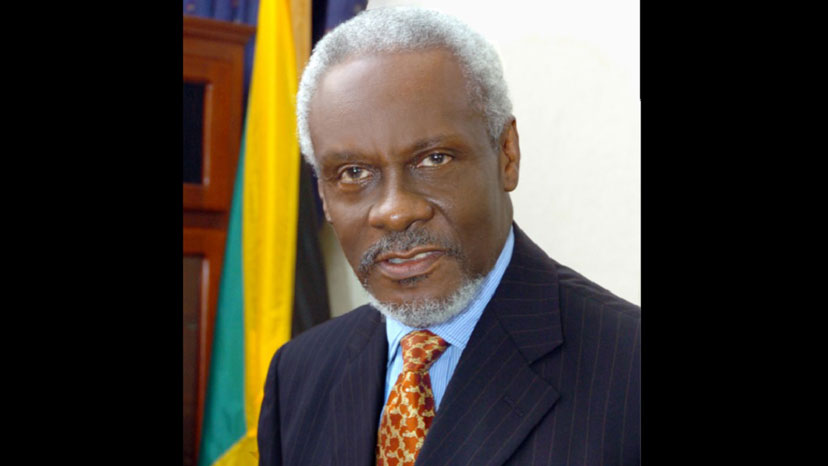

The bitter irony that haunts this decades-long saga is that the CCJ was originally championed by the JLP itself. Prime Minister Hugh Shearer first advocated for a regional final court in 1970, with Edward Seaga offering his support. Both JLP stalwarts recognized the fundamental contradiction of sovereign nations tethering their final judicial decisions to a former colonial power.

The historical record shows a maddening zigzag of JLP positions. In 1988, Seaga's cabinet—which included Bruce Golding—sent Attorney General Oswald Harding to Antigua explicitly to accelerate the creation of the court.

As Opposition Leader in the early 1990s, Seaga and Golding endorsed the recommendations of the Joint Select Committee on Constitutional and Electoral Reform that Jamaica should "pursue the CCJ policy in earnest." In 1995, Seaga's vote was critical to Parliament's unanimous acceptance of that report.

Yet in a bewildering reversal just months before the CCJ's 2005 inauguration, after the Privy Council declared that Jamaica's transition required a two-thirds majority vote in each House, Seaga announced his party's withdrawal from the process—offering explanations that ranged from peculiar to plainly indefensible. This abrupt about-face settled into a position that Jamaica should "closely assess" the court's operation before proceeding.

Two decades of operation have now passed. The CCJ has established itself as a model of judicial excellence and independence. Its innovative financing structure—an independent trust fund established with international loans—has shielded it from political interference. The court's itinerant nature, hearing cases throughout member states, has made justice more accessible than the distant chambers of London could ever be.

Not a single complaint has emerged from any of the five nations that embraced the CCJ's appellate jurisdiction. The court has garnered international acclaim for its jurisprudence. The objectives shared by Shearer and Seaga in 1970 have been thoroughly fulfilled.

Not a single complaint has emerged from any of the five nations that embraced the CCJ's appellate jurisdiction. The court has garnered international acclaim for its jurisprudence. The objectives shared by Shearer and Seaga in 1970 have been thoroughly fulfilled.

Yet Andrew Holness stands alone in his resistance, betraying the vision of his own party's founders. His reluctance has transformed what was once prudent assessment into stubborn obstruction, making him the solitary roadblock on Jamaica's path to full judicial sovereignty.

The burden of history now falls squarely on Holness's shoulders. It is his solemn duty to honor the direction established by his predecessors and to complete Jamaica's decolonization journey. The time for assessment has long passed; the moment for action arrived years ago.

For a nation where the vast majority trace their heritage to Africa, continuing to send final appeals to the heart of the former empire represents more than procedural inconvenience—it is a persistent echo of colonial subordination that grows more discordant with each passing year.

Prime Minister Holness now faces a stark choice: continue this two-decade charade of evaluation, or finally join hands with visionaries across the political spectrum who recognized long ago that true independence demands control of one's highest court. The clock has been ticking for twenty years. The patience of history wears thin.

These developments create a moment of profound symbolic potential. What better occasion for Holness to shed the mantle of hesitation than when he stands as the regional body's chairman while a fellow Jamaican ascends to the CCJ's highest office? The alignment of these events presents not merely an opportunity but a challenge to the Prime Minister: Will he seize this moment to complete the circle that his party's founders began drawing over half a century ago?

Hope, as they say, still springs eternal. The question remains whether Holness will transform this hope into the decisive action that Jamaica's judicial sovereignty has awaited for twenty long years.

-30-