The Role of the CCJ in Building a Caribbean Jurisprudence

The Court of Appeal of Jamaica was established by the Constitution of Jamaica when the country gained its political independence from Britain on August 6, 1962. It, therefore, like Jamaica, celebrated its 50th anniversary on August 6, 2012.

The new court has no inherent jurisdiction. It derives its authority from the Constitution of Jamaica and from its enabling legislation, which also gives it all the powers that the previous court enjoyed.

It hears appeals from all divisions of the Supreme Court of Judicature of Jamaica as well as all Resident Magistrates’ Courts. There is also provision for appeals directly to the court from the decisions of certain bodies, such as the General Legal Council.

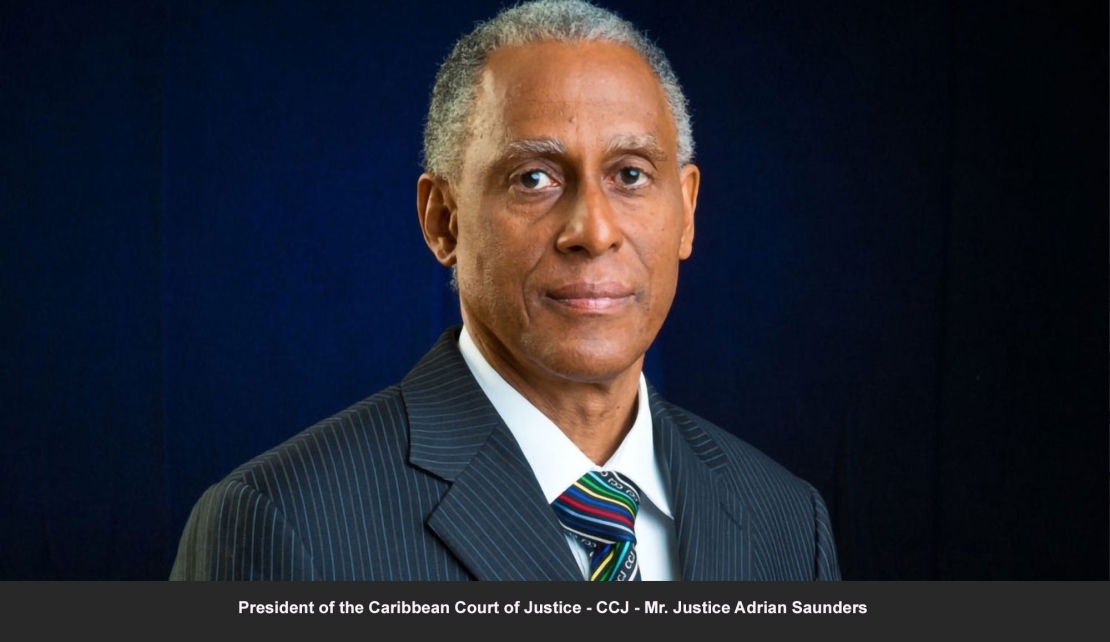

On the 6th of August, 2022, the Court of Appeal of Jamaica, celebrated its 60th anniversary. The President of the Caribbean Court of Justice, (CCJ) The Hon. Mr. Justice Adrian Saunders was asked to deliver the main address in commemoration of the anniversary which was held on the 3rd of August at the Jamaica Pegasus Hotel in Kingston. The following is the address delivered by Mr. Justice Saunders:

The Role of the CCJ in Building a Caribbean Jurisprudence

I wish to express my profound appreciation to The Honourable Mr Justice Patrick Brooks, President of the Court of Appeal of Jamaica, for the invitation to deliver this address. Patrick, you could have asked anyone in the Commonwealth and beyond to grace you on this special occasion and they would have gladly obliged.

I would like to think that the fact that you invited me attests, not just to our personal warm friendship, but rather, to the esteem in which you hold the Caribbean Court of Justice (CCJ). We are deeply appreciative.

Of course, as many of you are aware, I am always delighted to be in ‘Yard’. Since my time at the Law Faculty at Cave Hill I developed and have maintained a close friendship with many Jamaicans. This country has held and continues to hold very special memories for me.

I still vividly recall spending two weeks in Black River in 1974 with one of my closest friends at Cave Hill, Michael ‘Bucky’ Clarke of blessed memory. And how can I ever forget that memorable encounter I had one evening in 1975 at 56 Hope Road with its famous occupant, already a world superstar at that time.

Brother Bob took the time then to greet and personally entertain three starry eyed youth-men from Grenada and St Vincent and the Grenadines and to swap stories with them.

It's not just me, but all the people of the English-speaking Caribbean hold in very high regard the people of the most populous Anglophone Caribbean State; the first among us to blaze the trail of decolonisation.

We are struck by the tremendous pride and passion you demonstrate for your country. When Jamaica’s sports women and men excel internationally, as they invariably do, the entire region rejoices. And of course, the lyrics and melodies of Jamaica’s musical artistes continue to captivate the people of the entire region.

So, we join you in commemorating the diamond anniversary of both Jamaica’s Independence from colonial rule as well as the establishment of its indigenous Court of Appeal.

I assure you my good wishes come from a tremendous depth of sincerity. History records that it was this country’s GLEANER newspaper that in 19011 presciently articulated the need for a West Indian final court of appeal. That idea crystallized in 2001 when the Agreement Establishing the Caribbean Court of Justice2 (‘the CCJ Agreement’) was signed by 10 Member States of the Caribbean Community (CARICOM) including Jamaica.

Jamaica did not just execute the CCJ Agreement. It pledged to repay to the Caribbean Development Bank, and over a ten-year period it did in fact repay, approximately 27 million United States Dollars to help capitalise the CCJ Trust Fund created in order to insulate the Court and its Judges from any actual or perceived political pressures that might exist.

In their individual capacities, Jamaican nationals have made an enormous contribution to the operations and management of the Court. After the host country, Trinidad and Tobago, Jamaica has the largest complement of staff at the CCJ.

Several distinguished Jamaicans have also served, and several do now, as Commissioners on the Regional Judicial and Legal Services Commission (RJLSC), the independent body tasked with responsibility for the selection, the appointment, the terms of office and discipline of Judges and staff of the Court.

Jamaica and its judicial officers have both benefited from and invested time and resources in the pursuit of the goals of the CCJ. But even so, and especially considering the US$27million put into the Trust Fund by this country, the nagging questions that obviously arise are, has Jamaica realised a full return on all of that investment?

What should such a return look like?What is the opportunity cost of failing to realise that full return? Are there objective impediments to such realisation? If, so, what are they? Ultimately, it is the Government and people of Jamaica that must answer these questions.

Persons like myself must respect and abide by those decisions. Still, as President of the Court, I believe I am well positioned respectfully to offer a view for what that view is worth.

These questions have a special resonance in relation to the appellate jurisdiction of the Court and the role of a final appellate court. Those are the issues that I wish particularly to reference with a Jamaican audience this evening. In our original jurisdiction, where we interpret and apply the CARICOM treaty, a number of Jamaicans have accessed the Court both as counsel and as litigants.

We easily recall, for example, that it was a Jamaican national, Ms Shanique Myrie, who had the courage to file a case4 seeking to hold Caribbean governments to account for the obligations they voluntarily undertook regarding the CARICOM Single Market and Economy.

In each of these countries, as compared to what occurred prior to their accession, there has been a dramatic escalation in the volume of cases being adjudicated at the level of a second appellate tier. For the ten-year period before and after accession to the CCJ, for Barbados and Belize, the increase was in the magnitude of approximately 320% and 144%, respectively.

Let us briefly do a comparative survey for the period 2016 to 2021(inclusive). Let us also consider this. Jamaica has a population that is approximately 10 times that of Barbados; 7 times that of Belize and slightly less than 4 times that of Guyana.

During the period 2016 to 2021, a mere 20 second-tier appellate judgments were delivered by Jamaica’s highest court. During the same period the CCJ delivered 43 judgments from Barbados; 28 from Belize and 52 from Guyana.

If we zeroed in on Barbados, it is apparent that a country with 10% of Jamaica’s population has had more than twice the number of cases heard and resolved at the level of a second appellate tier. As compared with Jamaica, Guyana had more than two and a half times the number of cases heard and resolved at the level of a second appellate tier.

The reality is that comparatively few Jamaican cases are being decided by this country’s final court. I read recently that the Chief Justice, the Honourable Mr Justice Bryan Sykes, has estimated that the Jamaica Court of Appeal would usually render over 250 appellate decisions each year and that only about 3 or 4 of these cases are appealed further to the Privy Council.

What is the reason for such a paucity of cases going up to London? Surprisingly, there are some people who still express the view that the Privy Council is ‘free’ and that this is a good reason why we should continue to use it.

Such reasoning about freeness is simply absurd. The filing fees at the London court, coupled with the significant fees which must be paid to English solicitors, deter all but the well-heeled and legally aided from taking a case to London. The fundamental reason for the few Jamaican cases reaching London has to do with the crippling expense.

No other Commonwealth country with a population or land area the size of Jamaica sends its final appeals to be heard in London. Of course, whether a State decides to continue having Her Majesty’s Privy Council adjudicate its final appeals and British judges ultimately interpreting its Constitution and laws is a fundamental constitutional choice for that State.

But it is a choice that has consequences. I have already alluded to one such choice. People of ordinary means are deprived of the ability to avail themselves of a level of access to justice that they could and should enjoy.

There are other more systemic, subtle, less easily discernible consequences. These other consequences are wrapped up in the role of a second level court of appeal. As I noted in a speech I gave in Guyana earlier this year: In a healthy democracy, the citizenry has access to a range of courts and judicial officers, mostly judges and magistrates, to resolve their disputes in a civilized fashion. Invariably, in a fraction of those cases the losing litigant may lodge an appeal because it might be thought that the judicial officer has made an error, whether by mis-applying the law or by inaccurately finding or not finding certain facts, or by a combination of both.

The primary role of an intermediate court of appeal is to correct any such errors. The court of appeal corrects the error and, usually, that is the end of the litigation.

There would invariably be, however, instances where an appeal from the court of appeal’s judgment to a second appellate tier is warranted. The lawyers involved would have recognised this as a hard case; a case where the law is uncertain and is in need of clarification; or a case where interpretation of the law might admit two or more equally rational answers.

In our common law countries, where a significant body of the law is judge made law, a hard case might be one where the prevailing interpretation of the law appears to be way out of step with the ongoing march of an advancing society. In each of these cases, resort is usually had to the second-tier appellate court.

Then, the obligation of the final court is to consider and, if necessary, engage in a course reset. The role of an apex court is not just to correct errors made in a particular case. An apex court is a reflective body whose decisions go beyond the litigants in the specific case.

Those decisions are aimed at the judicial system as a whole. Apex courts engage in system-wide correction. For the rule of law to operate in the dynamic manner it should, it is vital that a final court should be accessible to all who have hard cases. It ought not to be available only to those with substantial means or those who can obtain legal assistance.

That is one signal disadvantage of sending appeals to London. The cases are legion where the CCJ heard hard cases that in all likelihood never would have reached the Privy Council. These were cases that made a profound contribution to the development of the law of the respective States from which the appeal was brought.

There is for example Ross v Sinclair, involving two women of very little means, where there was a great risk that the relevant statute which required interpretation was being wrongly applied. And, indeed, it turned out that it was.

There is Gibson v Attorney General of Barbados where there was a murder accused against whom there was only bite mark evidence. The impecunious accused desired state assistance to procure the services of a forensic odontologist.

Was the State obliged to render that assistance to Gibson as part of his right under the Constitution to the provision of adequate facilities to mount his defence? We said ‘No’, but quickly added that he was entitled to a fair trial and fairness in this case, given all the circumstances, required that the State should pay for the report of the forensic odontologist.

In the Maya Leaders Alliance case we have been doing something that I have not seen other courts in the region do. We have been monitoring the manner and pace of implementation of a very complex consent order in which the Executive is a party.

There is also Smith v Selby from Barbados where the Court was required to interpret purposely social legislation enacted to benefit common law spouses.

In a trilogy of constitutional/criminal cases, Nervais, McEwan and Bisram, the Court adopted an approach to pre-independence laws that has now placed us on a very different jurisprudential path from that taken by the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council so far as that question is concerned.

The cases raised issues of constitutional interpretation. Should Caribbean Constitutions be interpreted in such a manner that pre-independence laws should take precedence over constitutionalised fundamental rights even when it is accepted that those colonial laws infringe the fundamental rights?

Or should the Constitution be interpreted in a manner that requires the colonial laws first to be modified to bring them into consistency with the fundamental rights? The Privy Council has doubled down on the former path which they first took by a narrow majority in the Trinidadian case of Matthew v The State. In Nervais, McEwan and Bisram, the CCJ explained its reasons for not adopting that path. In our view, constitutionalised fundamental rights were too sacrosanct to be trumped by pre-independence laws.

In a healthy democracy, a decent percentage of the judgments of the court of appeal (perhaps about 10% – 15%) should be appealed to the apex court so that this court can, interstitially, and in partnership with the legislature, close the gap between law and society.

Can’t the court of appeal also play this role of protecting and advancing democracy, of closing the gap between law and society? The answer is, ‘Not really’, certainly not anywhere as effectively.

The apex court is far better equipped. It is not burdened with hundreds of appeals in which the central question is whether the trial judge erred. It usually has the most experienced and skilled judges. These judges sit together in a greater number than the courts below. Because they sit on far fewer cases, there is time for greater reflection.

For decades, Guyana maintained a system where the Court of Appeal was the final court. The results are there to be seen. Unsurprisingly, Guyana was one of the first countries to accede to the CCJ’s appellate jurisdiction.

The point is straightforward. When access to a second-tier appellate court is eliminated or compromised, choked off, a country’s jurisprudence will suffer tremendous harm. Some uncertainties in the law never get authoritatively resolved. The country’s jurisprudence becomes stultified and the gap between law and society widens.

The second important consequence of few appeals reaching a final court is this. Liberal democracy anchors itself in the operations and inter-relationship of three branches of government: the legislative, the executive and the judicial.

Democracy thrives when there is a mutually respectful debate and healthy tension between the decisions of the judicial branch and the workings of the other two branches. That debate is carried on via the judgments of the apex court.

Apart from deciding the litigation and clarifying the law, without overstepping its bounds, the final court may sometimes make suggestions for improvements in the statute law and/or the administration of the country.

These suggestions may or may not be taken up, but at least the populace is afforded an informed view. In cases like Cruise Solutions, Ventose, McEwan, and Bisram from Belize, Barbados and Guyana, respectively, both parliament and the executive authority have taken up such intimations by the CCJ with the result that the rule of law and the administration of justice have been improved.

There is one other important consequence to a country persisting with appeals to London. How do we justify to the little children that currently, 60 years on from independence, they can all rightly aspire to be the Prime Minister of Jamaica, to be the Chief Justice, or the Speaker of the House or the President of the Court of Appeal, but they cannot aspire to be the President of the country’s final court as that is a role reserved for a Britisher? How do we explain that to them?

It is painful to have to justify the legitimacy and competence of the region’s final Court and its judicial complement. It is especially egregious that one must do so in the face of contrary views from the most unlikely sources. I expected this when the Court just started, but not after 17 years.

Not after a record of efficient service; not after a fair body of jurisprudence has been built up that can easily be assessed, analysed and compared. Remarkably, it is only in the English-speaking Caribbean that the merit and worth of the CCJ are questioned. In the rest of the world and even among our colleagues in the United Kingdom, the CCJ is regarded with utmost respect.

The highest courts internationally including those of the United Kingdom (including the Privy Council) cite our judgments with the same high regard as we cite theirs. Still, there remains, in some quarters in the region, the notion that the judges of the CCJ are not or cannot be objective; that we are or can be ‘reached’ by politicians; that Caribbean judges can’t be trusted because our societies are too small and so on and so on.

Such reasoning is offensive. I regard it as a slander on me, on my colleagues; and too on the host of excellent Caribbean judges some of whom are Jamaicans and are in this room and who have distinguished themselves in just as worthy a manner as judges anywhere else.

It is true that at the levels below the CCJ and the Privy Council, some of our courtrooms in the region may be in need of repair, some of our IT systems may require improvement, so too our registry and case management processes, we may have delays (in some countries horrible delays) in the justice system (which judiciary does not?).

These issues are serious and also deserve attention, but they are entirely independent of the debate on the CCJ. Judicial fairness, judicial objectivity, judicial ethics, none of these traits have one jot to do with the size of a country or its population, or with who went to school with whom, or with geographical remoteness or cultural alienation.

These are matters that have to do with character and training and competence. It is regrettable that responsible persons should imply that while everywhere else in the world those traits abound, they are in short supply among Caribbean judges. Decent and right-thinking persons have a duty to reject and decry such corrosive insinuations.

It is easily possible to identify Caribbean jurists who have no less integrity and ability than jurists anywhere else in the world and in this room today I see wonderful examples of judicial objectivity, fairness and competence.

History has confirmed that the finest Caribbean jurists are just as capable and honest and ethical as the finest jurists anywhere else. An impartial and objective assessment of the Caribbean Court of Justice is best made by those who make a studied analysis of our judgments as Dr. The Hon. Lloyd Barnett did on the occasion of our tenth anniversary.

We are happy for such an assessment to be made by those who critique our strategic agenda and our court processes, by those who have directly interacted with the Court. What is telling is that all of our judgments have been complied with; even those that were extremely bitter pills for incumbent governments to swallow. And in Barbados and Guyana there were not a few such decisions. I think this attests to a high level of observance of the rule of law in the region and in particular to commendable respect for the integrity of the Court’s judgments.

I am also satisfied that, both in the original jurisdiction and especially in those States that have given us the honour of hearing their final appeals, we have contributed to clarifying and elevating the rule of law.

The CCJ Agreement makes clear that the Court was intended to ‘have a determinative role in the further development of Caribbean jurisprudence through the judicial process’. The leaders of CARICOM also considered that the establishment of the Court represented ‘a further step in the deepening of the regional integration process’.

By dint of our independence and a fierce commitment to excel, a commitment shared alike by judges and court staff, the Court has over the years taken its mandate very seriously. We see it as part of our responsibility not simply to function as a depository for appeals and applications that must be processed and judgments on them delivered.

We do that of course but, in addition, we regard it as a part of our duty to contribute to the enhancement of efficiencies within the legal profession and to take steps that would improve the administration of justice throughout the entire region.

Indeed, we consider this to be an essential aspect of our role in the further development of our Caribbean jurisprudence. We have done this through the use of at least four platforms.

Firstly, the Court’s educational arm, the CCJ Academy for Law (formerly the Caribbean Academy for Law and Court Administration), has spearheaded a number of capacity-building initiatives in the region with both the legal profession and the judiciary.

Secondly, at the behest of the Heads of Judiciary of the region, the CCJ has invested time and effort in the establishment and operations of the Caribbean Association of Judicial Officers (CAJO).

Over the last 13 years, CAJO has provided a range of judicial education training opportunities for judges, magistrates, registrars and court administrators all across the region. CAJO’s biennial conference attracts judicial officers from both the English and Dutch Caribbean, and it has been an ideal forum for sharing information and best practices.

Thirdly, the international community has identified the CCJ as an appropriate executing agency for donor-funded projects designed for justice improvement throughout the region. So, for example, over the last eight years, the CCJ was the executing agency for the Canadian-funded Judicial Reform and Institutional Strengthening (JURIST) Project.

The JURIST Project has engaged in several initiatives including the establishment of a Sexual Offences Model Court in Antigua and Barbuda, the development of Model Guidelines for Gender Sensitive Adjudication in collaboration with CAJO and UN Women, and the establishment of the soon-to-be-launched Caribbean Judicial Information System (CJIS). The CJIS will serve as an information hub for judiciaries across the region and will enable effective storage and access – internally and externally – to information such as judgments, policies and procedures, project information, rules and guidelines, and the like.

Fourthly, working with Caribbean software engineers and solution architects, the CCJ helped to develop the Caribbean Agency for Justice Solutions (formerly APEX) which provides cutting edge court technology-related solutions for judiciaries in the region. I think I should say a little more about the background to this institution.

Due to the diverse and geographically dispersed customer and stakeholder base of the CCJ, we have been obliged to push the envelope in delivering effective and efficient justice services. Long before the pandemic, the CCJ was holding remote hearings that were video-conferenced.

In about 2016, working with Caribbean software engineers, work commenced on the building of an e-filing and case management software that was deployed at the Court in 2017 and is second to none in this part of the world. If you visit our Registry today, you will find terminals and screens. What you will not see are stacks of paper.

Last week both Chief Justice Sykes and I attended the Conference of Caribbean Heads of Judiciary in the Cayman Islands. It was an extraordinarily productive conference in which there was a mutual sharing and exchange of ideas and best practices on diverse aspects of theadministration of justice.

I was especially heartened by the presentation that was made to regional Heads of Judiciary jointly by the Caribbean Agency for Justice Solutions and the staff of the Cayman Islands judiciary.

The Agency has recently deployed its technology solutions in the Cayman Islands and the presentation confirmed that while there are judiciaries in the region seeking to invest in case management systems from Singapore, from Europe, from the United States, from Nigeria and wherever else, our own home-grown software was not only just as effective but it offered greater possibilities for continuous development tailor-made to suit the specific needs of the Caribbean. The parallel with the CCJ could not have been more apt.

Over the years, the CCJ has also paid tremendous attention to our underlying administrative and other processes that support the receiving, processing and adjudication of our caseload and outreach initiatives. Our aim is truly to live our Mission to provide ‘accessible, fair and efficient justice for the people and States of the Caribbean Community’ and to realise our Vision, which is ‘To be a model of judicial excellence’.

The aim of the CCJ is to lead by example. We continuously engage in an iterative 4-step improvement process of assessment, analysis, implementation, and evaluation to ensure that our court infrastructure, our management systems, our methods and processes are in alignment with our vision of court excellence. This year, the Court was honoured to be admitted as an implementing member of the International Consortium for Court Excellence - the first court within this region to be so admitted.

Colleagues, friends, the CCJ has endeavored to justify the decision taken by the governments and parliaments of Guyana, Barbados, Belize and Dominica (and hopefully soon Saint Lucia) to alter their Constitutions to send their appeals to us.

I sincerely believe that such accession offers the best opportunities for advancing both our region’s jurisprudence as a whole and that of each State. Accession also ensures that, yes, the children of the region will be able to one day hold the office of President of their own final court of appeal.

Colleagues and friends, anniversaries provide an ideal opportunity for retrospection, introspection, and contemplation of the future; an occasion for reminiscing on the dreams and goals once cherished; the choices made in seeking to fulfill them, and the results achieved.

This must surely be the case with a 60th Anniversary. As you engage in these 60th anniversary celebrations, permit me to say once again how honoured I am to have been invited to share with you in some of these celebrations and reflections.

As I close, let me reassure you that whether Jamaica ultimately chooses to send their appeals to the CCJ or you take a different path, neither step will impair the camaraderie, the mutual learning and sharing that will always exist between the judiciary of Jamaica and the CCJ.

This country is an important member of the Caribbean Community and the CCJ shall forever continue to draw on the skills and expertise of the people of Jamaica. This country will always be an important part of our source pool for appointment whether as judges or staff members of the CCJ or of members of the RJLSC. The CCJ shall continue the same outreach to Jamaica as we have done with all other CARICOM States.

I thank you.

The Original document can be accessed at the following address- https://ccj.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/Saunders_20220803-1.pdf