UNITED STATES | The Caribbean Diaspora's influence on the United States

The United States of America has always boasted that the Caribbean represents its ‘third border’ to complement that of Canada in the north and Mexico in the south.

In that regard, in much the same way that Canada is regarded as a “Most Favoured Nation” and Mexico is consistently the United States' second-largest export market after Canada, the Caribbean is regarded as "vital partners on security, trade, health, the environment, education, regional democracy, and other hemispheric issues.”

Despite this however, the United States often undervalues its relationship with the Caribbean, choosing to pit one country against the other in the classic ‘divide and conquer’ methodology rather than approach the development of the region in a holistic manner.

Some forty years ago, in response to the inroads that had been made by the Soviet Union in the region, US President Ronald Regan introduced the Caribbean Basin Initiative (CBI). It was designed to act as a soft-power initiative to counter the Soviet Union’s western push, and to promote and strengthen Caribbean democracies.

The CBI provided benefits tor seventeen Caribbean Basin countries by providing advantageous access to U.S. markets. The CBI offered a way for them to catalyze local development, allowing them to make economic strides toward liberalizing reforms.”

During his fact finding trip to the United States in early July, Mr. Golding visited with the Jamaican Diaspora in four United States cities including Washing DC and New York.

The Jamaican Opposition Leader and People's National Party President, was invited to participate in the Caribbean Research Center’s prestigious Speaker Series at the Medgar Evers College of the City University of New York.

The City of New York, as Golding indicated, is where “arguably the greatest concentration of Caribbean people residing outside of the region live and work, and have raised generations of proud Caribbean-American children.”

Mr. Golding was asked to deliver a lecture on “The Caribbean Diaspora's influence on the United States,” to which he responded that the influence of the Caribbean could be felt from its historical foundations during the 17th century.

This was when enslaved Africans were first brought from Barbados in the Caribbean by slave-owners to work in South Carolina, up to the present time, when emerging from the 2020 US General Election, a first-generation Caribbean-American, Kamala Harris, daughter of Jamaican economist Professor Donald Harris, and a Tamil Indian mother, appeared on the presidential ticket and went on to be sworn in as the first female Vice President of the United States.

The following is the full text of the PNP President’s lecture to the audience at the Medgar Evers College of the City University of New York on the 21st of July 2022.

The Caribbean Diaspora's influence on the United States as Jamaica celebrates 60 years of independence

I wish to recognize the members of Faculty, students, staff and administrators of the Medgar Evers college of the City University of New York- or as we would say in Jamaica, “Big up to the Cougars in the house”.

It is indeed a distinct pleasure to participate in the Caribbean Research Center’s Speaker Series. I must thank Dr. Ken Irish-Bramble, Executive Director for the Caribbean Research Center, for extending the invitation to contribute to this prestigious Speaker Series.

I must admit, there is a special excitement about engaging with you in New York City – in Brooklyn no less – the birthplace of the great Jamerican Notorious B.I.G. himself. New York, where arguably the greatest concentration of Caribbean people residing outside of the region live and work, and have raised generations of proud Caribbean-American children.

I must admit, there is a special excitement about engaging with you in New York City – in Brooklyn no less – the birthplace of the great Jamerican Notorious B.I.G. himself. New York, where arguably the greatest concentration of Caribbean people residing outside of the region live and work, and have raised generations of proud Caribbean-American children.

To grasp this, one only has to recall the vibrant images of the annual Labor Day parade; or, on a more granular scale, one only has to go into one of the myriads of small business establishments that have been built by Caribbean entrepreneurs over decades, ensuring that a piece of the Caribbean is always available here.

Whether it is a beef patty, peas and rice, souse, jerk chicken, cornmeal porridge, even in the dead of Winter, here in New York one can feel to centrality, the importance and the impact of the Caribbean and Caribbean people on this place. The powerful vibe of our culture and way of life is well represented in all its glory in New York.

So, to deliver this lecture this evening is a distinct honour and privilege. That said, and in spite of the references I just made, I wish to begin with the strong assertion that the impact of the Caribbean on the United States of America is not limited to festival and food.

Too often, these are the predominant and limited images of who we are, and where and how we have contributed, without adequate expression of the seriousness, scope, and capacity of Caribbean peoples’ social, political, cultural and historical engagement in this country.

I must begin with the historical foundation for the Caribbean Diaspora, which was during the 17th century when enslaved Africans were brought from Barbados by slave-owners to work in South Carolina. We must recall that until 1776, much of the Caribbean, then the “British West Indies”, and what is now America, were all British colonies – bound together not by sharing contiguous land, but by law, culture, the brutal realities of the Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade, and the courageous acts of resistance through which our enslaved fore-parents in in these lands fought to secure liberation.

During the18th century, the majority of enslaved persons in the northern states were transported from the Caribbean, outnumbering those brought directly from Africa, up to 20 percent of enslaved persons in South Carolina were from the Caribbean.

Along with South Carolina, Virginia and New York, a large Caribbean community expanded in Boston. By 1860, just before the Civil War commenced, it is estimated that one of five Bostonians were born in the Caribbean.

So, when we talk about the important role of Boston in the anti-slavery movement, we must account for the presence of black people from the Caribbean, who played an important role in the struggle alongside US-born activists.

Indeed, Boston became a hub of both the national and international antislavery movement, and commemorated each year the anniversary of emancipation in the British West Indies on the 1st August 1834, even while fighting for enslaved persons still laboring in bondage in states south of the Mason-Dixon line.

And of course, we must acknowledge the tremendous significance of the war of liberation and independence waged by the enslaved people of Haiti against France and its Western allies from 1791, led by the brilliant military strategist and freedom fighter, Toussaint L’Ouverture.

The success of their struggle led to Haiti becoming the first black Republic in the Western Hemisphere, established as a sovereign state in 1805, and the first nation in the World to constitutionally guarantee the freedom of all people, regardless of race. The impact of this momentous achievement by Haiti on the freedoms eventually attained in the rest of the Caribbean and in the United States, cannot be overstated.

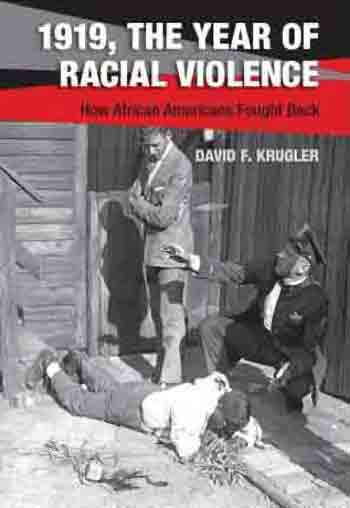

They were not met with open arms, and in the bleak summer of 1919, anti-black violence surged in cities across the US against the influx of migrants from both the South and from the Caribbean.

Called the “Red Summer” because of the blood that flowed in northern city streets, the great Jamaican poet Claude McKay, then living and writing in New York, penned the iconic poem “If We Must Die” in homage to the bloodshed taking place.

Many of you would be familiar with that inspirational poem. We recited it in school as likkle children in Jamaica, and no doubt many of you did so too, whether you went to school in Kingston or in Jamaica Queens.

So my friends, the history of this country is deeply entwined with, and cannot be extricated, from the history of the people of the Caribbean. While the flow of immigrants from the Caribbean to the US was tightened in the mid-1920’s after the passage of the Immigration Act of 1924, the Ellis Island Museum displays the names of countless Caribbean nationals who sailed into New York Harbor and saw Lady Liberty welcoming them to America.

Of course, the America they would encounter on arrival was not always the one they had imagined.

That man was of course Marcus Mosiah Garvey, Jamaica’s first national hero. In 1920, Garvey and the UNIA held a delegates conference in Harlem that was attended by more than 25,000 persons from across the world.

We should never understate, and it is important that we, as the Rastafarian elders would say, seek to overstand, the deep and abiding impact of Garvey, the UNIA, and the social, political, cultural and economic vision of Garveyism, not just on the Caribbean and African diaspora, but on the United States of America.

Between 1941, during World War, and 1950 some 50,000 Caribbean nationals migrated to the U.S. Several originally came as farm workers, working on sugar and tobacco plantations in Florida and other states, but over time they left the farms to relocate to cities like New York and Boston, as they found ways to change their status from farm workers to landed immigrants who could remain legally in this country. Having achieved this legal status, many then brought their relatives from the Caribbean to join them in the Diaspora, under the American immigration concept of Family Reunification.

These early members of the Caribbean Diaspora included people like Carlos Juan Finlay from Cuba, who having determined that mosquitoes were the cause of yellow fever, helped to eradicate the disease in the US.

Many of the famous writers and artists during the 1920’s Harlem Renaissance were either born in the Caribbean or of Caribbean descent.

Some great examples include:

- Nella Larsen, who published several novels including “Passing”, which was recently adapted to a film some of you may have seen. She was of paternal Caribbean parentage (her father was from what is now Suriname);

- Arthur Schomburg, after whom the famed Schomburg Library in Harlem is named, who migrated to this city from Puerto Rico;

- Cicely Tyson, the outstanding stage and screen actress, who was born in Harlem in 1933 as the daughter of immigrants from Nevis;

- Hazel Scott, the African-American classical and jazz pianist, who was an immigrant from Trinidad & Tobago and was raised in New York City from the age of four, and later became the wife of Legendary Black U.S. Congressman, Adam Clayton Powell, Jr;

- And of course, Malcolm Little, later Malcolm X, who was the son of a Grenadian mother and a father who was a self-declared Garveyite. Malcolm himself expressed that he was influenced by Garvey’s values of Black pride and self-reliance, taught to him by his father.

The US tightened its immigration laws again in the 1950’s, introducing a rigid quota system, but in 1965 President Lynden Johnson’s Administration passed a new Immigration Act which liberalized immigration to the United States and resulted in a resurgence of Caribbean migration.

It is estimated that approximately one million Caribbean immigrants came to America between the 1970’s and the early 1990’s, nearly half of them from Jamaica, with the vast majority settling in the New York, New Jersey, Connecticut tri-state area.

While history may not highlight the achievements of many of these early immigrants, they placed significant emphasis on education; and, most importantly, they ensured their offspring, born and raised in the US, were imbued with strong values, positive self-belief, the spirit of innovation and entrepreneurship, and a sense of civic responsibility and community engagement.

Those early 20th century Caribbean migrants have thereby left an indelible imprint on the American society, and they are honored by the outstanding achievements of so many of their descendants.

Among the notable figures from the second generation are:

- Minister Louis Farrakhan, who was born in New York in 1933 to Sarah Mae Manning, an immigrant from St. Kitts and Nevis;

- Harry Belafonte, also born in New York City, whose father was Harold George Belafonte, Sr., a Jamaican chef;

- J. Bruce Llewellyn, a businessman who was the Chairman, CEO and a part owner of the Coca Cola Bottling Company, and also a founding member of the 100 Black Men of America, born in Harlem to Jamaican mother and Guyanese father;

- General Colin Powell, a former Chairman of the US Joint Chiefs of Staff and US Secretary of State, was born in Harlem to Jamaican immigrants from the parish of St. Elizabeth;

- And, of course, US Congresswoman Shirley Chisholm, a legendary colossus of American politics, was born in Brooklyn to parents who were Guyanese and Barbadian immigrants.

Shirley Chisholm served on the New York General Assembly prior to her election to the US Congress in 1964. She holds the historic distinction of being the first Black woman to serve in the United States Congress, and also the first woman and first Black Woman to run for the presidency of the United States of America.

Friends, I want to pause for a minute and take us back a little to the beginning of this talk, to move us forward. I want us to consider together for a moment, this concept of diaspora.

I am not focusing on the dictionary meaning of the word. It is a deeper thing than that.

When you check a stock, as we say in Jamaica, it is like when we talk about where our navel string cut. For Caribbean peoples, whether in 18th century or the 21st century, whether first-generation, second or beyond – no matter where we go, our navel string cut in the Caribbean, and more specifically in our countries either of birth, origin, or cultural claiming.

And that is why you find that wherever we go, we carry, literally, our symbolic umbilical cords with us, and it is these cords that transcend time and space. It is those cords of deep connection that allow us to come together, in community, as a Caribbean Diaspora.

During the 1970s, the Caribbean Diaspora in the US grew exponentially, with significant numbers of our people again pouring into the New York region, and a new trend emerging of settlement in South Florida.

Like their predecessors that cemented a strong Caribbean Diaspora in the early to mid-20th century, the migrants who came to US in the later years of the century were ambitious, determined to make a success of their life, and driven by positive ambition. They did not shy away from instilling their culture on the American society, creating a new Caribbean-American culture that is so richly exemplified in music, dance-forms, theater, cuisine and overall achievement.

Today across America, the phenomenal beats of reggae and dance hall music are everywhere. The impact of artists like DJ Kool Herc on the birth and flourishing of hip hop here in New York, cannot be overstated.

Reggaeton is another genre that is directly influenced by music from Jamaica and the Caribbean. Soca from Trinidad and Tobago, and Kompas from Haiti, have also had a strong influence on US culture.

And then there are the name-brand artists from the Caribbean, such as Sean Paul and Shaggy from Jamaica, Nicky Minaj from Trinidad and Rihanna from Barbados, who have dominated American, indeed global, popular culture.

And before they emerged, Bob Marley had moved beyond being a musical legend, having transcending into a timeless icon of the struggle for social justice and resistance to oppression in whatever form and from whatever source.

As strong as the influence of Jamaican music is in the US, this influence is rivaled by the influence of Jamaican food. Take the Jamaican patty. In the 1970s and early 80s, when the influx of Jamaicans to the United States really peaked, it wasn’t easy to find a Jamaican patty shop.

Today, the Jamaican patty is a popular and pervasive food item in the US, found in large supermarket chains. Several schools now serve our patties for lunch to students across America.

And I could not stand before you here in New York and not pay tribute to, and attribute a significant contribution to the global reach of the Jamaican patty to, one of the most successful Jamaican businesses in New York, Golden Krust. The operators of this fast-growing US franchise have indeed helped to crown the Jamaican patty here in America.

But in addition to the patty, Americans are eating more varieties of Jamaican food than ever. In American restaurants it has become common to now see “Jerk this” and “Jerk that” on the menu. The ultimate Jamaican delicacy of oxtail and beans, that was once regarded as low on the “stocious” social ladder, is now in such high demand across the US that it is more expensive than steak and chicken, and has even found its way onto many a Michelin Star menu.

It is amusing to learn that Americans, who once couldn’t tolerate spicy food, now heartily consume the popular Jamaican curried goat and curried chicken, and a wide range of delicious rotis from Trinidad and Tobago and Guyana.

Thanks to the influence of Jamaican and other Caribbean food in New York and other parts of the US, a vibrant market has developed in the US for Jamaican and other Caribbean produce, spices and juices, boosting local business communities and our regional exports.

However, as I said earlier, as important and amazing as these things are, we are not only festival and food, bacchanal and bully beef, dance hall and dumpling…

The influence of the wave of Caribbean-Americans in the second half of the 20th century expanded significantly into the fields of business and politics. Thriving Caribbean business communities emerged in New York, Florida and Georgia.

A successful Caribbean media industry also blossomed, mainly in New York and South Florida where the high concentrations of Caribbean-Americans reside, and continues today, primarily in the form of free-to-air and online broadcasting.

As the numbers of Caribbean immigrants increased, and the first generation of Caribbean-Americans came of age, more Caribbean-Americans entered the American political arena.

Notably among these political pioneers are the beloved Una Clarke and her esteemed daughter Yvette Clarke in New York. Miss Una served on the New York City Assembly, while Congresswoman Yvette Clarke represents the 9th Congressional District in New York.

Happily, while the Caribbean Diaspora has succeeded in building a strong community in the US, most also maintain a strong connection with their homelands in the Caribbean. As I said before, the navel string, the umbilical cord, though geographically cut is never culturally, psychologically or spiritually severed.

Despite all this, the Caribbean Diaspora is too often primarily seen as making a significant contribution to the Caribbean through financial remittances.

It is true that, even as Jamaica proudly celebrates 60 years of political independence on August 6th, the nation continues to be dependent on the vast input from its Diaspora.

The importance of remittances to the Caribbean is reflected in the economic data. According to the Jamaica Information Service (JIS), remittances from the Diaspora to Jamaica reportedly reached US$3.3 billion in 2021, representing an increase of over the US$2.9 billion sent in 2020, and are a vital source of Jamaica’s foreign exchange earnings. In addition to the balance of payments impact, Caribbean economies are more buoyant because of remittances and, most importantly, many Caribbean families are sustained by remittances.

But there is much more to what Diaspora members contribute to the Caribbean than the money you sent home. Much more needs to be done to leverage the vast potential that resides in the experience, qualifications and other capacities of Caribbean Diaspora members in contributing to national development in Jamaica and other Caribbean countries.

I therefore want to stress to you this evening, ladies and gentlemen, that the input of the Caribbean Diaspora far exceeds foreign exchange. The Caribbean, and my country Jamaica, also need your skills and your talents to help us tackle our fundamental developmental challenges.

Modalities for your engagement and participation in our national life need to be further developed, and I am committed to assisting in that process. Modern technology has greatly enhanced the possibilities for broader and deeper Diaspora engagement, so what is needed now is political will and consistency of effort.

And as we seek to harness your spirit and capabilities, we must also acknowledge and celebrate all that has made you such an indomitable force in the Diaspora.

We recognize the sacrifices that it takes for a person to pack up and leave home, sometimes for the very first time; to leave family, friends and all that they have known their entire life, to enter the unknown that is “farrin”. Stepping into a new culture, and for some a new language. Stepping into a new geography, literally and symbolically.

I recognize what it means to navigate complex and challenging systems – government, politics, even transportation. I don’t envy anyone who comes from the Caribbean for the first time to New York and has to learn the Subway system. And to do so in winter…“rispek due”!

But our people have done all this, and done so without a fuss. They have just got on with it.

I know that Caribbean immigrants often have to sort out their immigration status and settle themselves personally, before they can become active in community life.

We know that many yearn for their families left behind in the Caribbean, and work tirelessly towards the reunification with their loved ones.

I am also keenly aware that many of the millions of undocumented persons in America are Caribbean people; and that this separation can lead to the breakdown of families and deep anguish, when persons are faced with the reality of being unable to return home to visit a sick loved one or to say goodbye at a funeral.

But despite the uphill climb as immigrants to America, Caribbean people have tremendously influenced, and indeed altered in positive ways, the diversity, complexity and characteristics of the American body politic. We are proud of the impact you have made and will continue to have on so many aspects of American life.

Those of us home in the Caribbean embrace and feel empowered by your accomplishments despite the struggle of adjustment and integration. When one of you achieves greatness, your entire Caribbean family celebrates with you.

We in the Caribbean continue to experience challenges when it comes to infrastructure, education, healthcare, domestic and transnational crime, the impacts of climate change, access to investment funding and recovering from the Covid19 Pandemic, among other issues. But we are a resilient people.

While Jamaica at 60 has seen advances in many areas of social and economic life, and enjoys strong democratic governance irrespective of which political party has formed the government since 1962, the resilient and resourceful spirit of our people remains our number one asset; and members of the Diaspora, you are our number one ambassadors.

I know that members of the Caribbean Diaspora wear your pride for your home countries on your sleeve, no matter where in the Diaspora you reside and what spaces you occupy.

Vice President Kamala Harris was reported to have said in a national interview before she became VP that she has “Juicy Beef” patties in her refrigerator.

The plethora of Caribbean-American organizations that exist in the Diaspora are a testament to the commitment that members of the Caribbean Diaspora have for their homelands.

From alumni associations to professional associations to groups of friends who get together to “form partner” and pool their resources to support their countries, that support is invaluable.

Know that members of the Diaspora are part and parcel of the Caribbean community, and that we are one family wherever we reside.

In closing, I want to acknowledge the milestone of Jamaica’s 60th Jubilee, and the pride all Jamaicans feel in the country’s attainment of 60 years of independence.

Of course, as far as nations go, Jamaica is still a youth. There is much work to be done as the country moves ahead.

As we look forward to the future, I, from the depths of my heart, want to thank Jamaicans overseas for your unwavering support of the land of your birth, and encourage you to continue to have our backs.

I thank the Diaspora for all the work you have done over these 60 years in helping in various areas of development in Jamaica.

Your efforts are well appreciated, and the people of Jamaica thank you. We look forward to the continued engagement with the Diaspora and cementing greater linkages.

Thanks for coming out tonight, and God bless you all.