AFRICA | Wretched of the Earth has been translated into South Africa’s Zulu language – why Frantz Fanon’s revolutionary book still matters

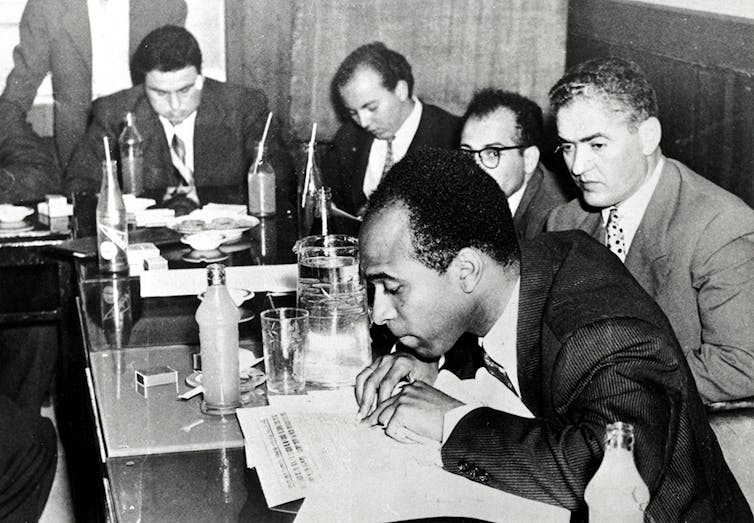

Frantz Fanon was an influential psychiatrist, Algerian revolutionary and pan-African thinker who was born on the Caribbean island of Martinique. His work – and particularly his final book The Wretched of the Earth (1961) – is still widely referenced to understand the fight against colonialism and also the postcolonial era in Africa. This global classic has already been translated into numerous languages – and is now available in South Africa’s Zulu language as Izimpabanga Zomhlaba thanks to poet, short story writer, anthologist – and now translator – Makhosazana Xaba. We asked her about the book.

Why is it important that books like this be available in isiZulu?

Although newspapers in isiZulu have existed since the mid-1800s, only Ilanga lase Natal, founded in 1903, has survived. But the readership for isiZulu literature is massive.

IsiZulu is the majority language in South Africa; 23% of the population speaks it as their first language.

Yet English and Afrikaans are the majority languages for the country’s publishing industry because of the politics of settler-colonialism and the persistent legacy of the apartheid regime that ended formally with democracy in 1994.

What is the book about?

One scholar called The Wretched of the Earth “a handbook for liberation”. The genesis and focus of this book of five chapters is the Algerian revolution (1954-1962). Fanon uses examples and lessons from the African continent, the Caribbean and beyond to show the similarities in how colonialism works and how revolutions unfold in response.

Fanon’s ideas on independence are pertinent to countries that have been under colonial rule, the African continent included. His writing straddles disciplines – politics, philosophy and psychiatry – as he shares his ideas and draws from his observations, experiences and the writings of others in Martinique, France, Algeria and Tunisia, countries he lived in.

The first chapter discusses the common-sensical armed struggle response to the violence of colonisation and how this necessity changes after independence when everything must be reconsidered.

Chapter two discusses the gap between the rural or peasant masses and traditional leaders and the people in towns, mostly political party cadres. It analyses the differences and calls for a “more flexible, more agile response” when addressing these differences.

The third chapter is an analysis of what happens after the revolution against domination and oppression ends and independence is gained. Fanon demonstrates how some of the formerly colonised people – party politicians, the national bourgeoisie, intellectuals, cultural practitioners, former activists, and more – take positions that are opposed to the revolutionary ones. They engage in actions that betray the revolution, like ultranationalism, corruption, patronage, chauvinism and more.

The fourth chapter is on national culture. Fanon makes the argument that this needs to change after independence and focus on building everything anew.

In the final chapter he uses case studies of Algerian and French patients he attended to while working in a psychiatric hospital in Blida, Algeria. Fanon clarifies the connections between the impact of colonial struggle on mental health.

With passion Fanon concludes the book by calling for a humanity that is different from that of colonisers.

Why is it still so relevant?

Fanon remains relevant today for many reasons. For instance, in the third chapter, he analyses “the trials and tribulations” of national consciousness in a manner that resonates with South Africa. The poor showing of the African National Congress (ANC), the former liberation movement, in the country’s 2024 elections is proof that South Africans have had enough of the spectacular failures of the ANC-led government.

Fanon challenges us to rethink all human relations. For me as a woman living in South Africa, known as the “rape capital of the world”, and as a Black person who still experiences racism, this call to rethink humanity feels urgent. The bill of rights asserts our dignity, freedom and equality, yet abusers, racists and rapists do the opposite; they dehumanise us.

It is easier today to point out what is wrong and challenge government, politicians and employers (and we should!) but how do we learn to challenge ourselves so that as perpetrators and victims we are on new journeys of rethinking human relations?

Fanon begins the book’s conclusion of four and a half pages with these words:

Now, comrades, now is the time to decide to change sides. We must shake off the great mantle of night which has enveloped us, and reach for the light. A new day which is dawning must find us determined, enlightened and resolute.

It takes self-reflection to arrive at determination, enlightenment and being resolute.

Who was Frantz Fanon to you?

Fanon was a writer like many others that I read and liked because they made a lot of sense. I was aware that he is revered within the activist circles where I moved. As I read the ever-growing scholarship on Fanon, I realised that his ideas had even more currency in the world than they did in my head.

One book on the translations of The Wretched of the Earth into other languages contextualises the biographies of each translation in a way that makes the relevance of Fanon’s ideas very clear. Unsurprisingly most of these translations were linked to the moments of political activism in the various countries.

Fanon has become somebody to me now that I have translated The Wretched of the Earth. I have been initiated into translation by Fanon’s book.

Makhosazana Xaba, Associate Professor of Practice, Faculty of Humanities, University of Johannesburg

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.