Shaka Zulu is back in pop culture – how the famous King has been portrayed over the decades

Shaka Zulu is one of the most famous figures in South African history, even though not much is actually known about him. The subject of a hit 1980s TV show and of many books, Shaka is reframed by each generation. Now he’s back in popular culture with a major new South African TV series, Shaka iLembe. Dan Wylie is an English professor who has written two academic books on Shaka. We asked him four questions.

Who was Shaka Zulu and what did you learn from writing about him?

Shaka kaSenzangakhona is universally recognised as the founder of what would become known as the “Zulu nation”. He ruled from about 1817 until he was assassinated by his half-brothers in 1828. He’s credited with elevating the Zulu from a fairly insignificant group, one among others, to a more unified “state”. Shaka conquered, incorporated, or allied with neighbours such as the Mthethwa, Ndwandwe, Hlubi, Qwabe and Mkhize to dominate a 200km-wide area north of the present-day city of Durban.

In my view, the unity of this state, the level of violence employed to achieve it, and Shaka’s responsibility for knock-on violence further inland have been hugely exaggerated.

I began writing a PhD study of the numerous white images of Shaka. These ranged from the earliest monstrous depictions of the mid-1800s, through sundry novels, poems and illustrations to the notoriously ahistorical 1986 TV series Shaka Zulu (in which African spirituality is reduced to screeching Gothic light shows and Shaka is a snarling killing machine). My study was published as Savage Delight, an investigation of how long-entrenched European images of “savagery” were applied to Shaka to support the ideologies of colonisation and apartheid. This over-simplified stereotype of Africans being prone to unbridled violence has fed into the ongoing Zulu self-conception as a fundamentally “warrior nation”.

I learned three main things. First, that a great deal of what had passed as factual and accepted “history” was actually pure fiction. Second, that such inventions were driven by much wider aesthetic, social or political currents – and are difficult to erase from popular consciousness. And third, that no professional scholar had attempted a full-scale biography of Shaka solidly based on available historical evidence.

So in Myth of Iron I set myself the task of reassessing the sources – both the highly unreliable white eyewitness accounts and newly available Zulu oral-historical material in the James Stuart Archive. I cut away the accumulated mythology to see what emerged.

In my biography I try to view Shaka as a flesh-and-blood human being, conducting his leadership within real political and environmental constraints. My conclusion was that we know astonishingly little for certain about him. Not when he was born, what he looked like or exactly when or why he was killed. Never mind his inner motivations. It’s astonishing, since Shaka is probably the best-known southern African black leader after Nelson Mandela. From oral sources a scholar can glean a better idea of inter-group political dynamics than of the man himself. Precisely in this gap in secure knowledge, myths have flourished.

Why is he such an enduring figure in popular culture?

Everybody loves a demon who can be blamed for society’s ills; or a hero who can be posed as a role model. We’re all fascinated by the execution of supreme power. And where solid evidence is lacking, storytellers step in to shape a character to their own ends.

Shaka has proved richly available and malleable. Colonials could use his alleged monstrosity to political advantage; Zulu nationalists could use his alleged military genius to theirs.

Hence such literary works as South African poet Mazisi Kunene’s epic poem Emperor Shaka the Great or Senegalese politician and poet Leopold Sédar Senghor’s play-for-voices Chaka, in which Shaka becomes a symbol of resistance to colonialism for all of Africa and all times.

What myths have shaped his image in popular discourse?

Most can be broadly lumped under “monster” and “heroic genius”. The first white eyewitnesses were small-scale traders and adventurers Nathaniel Isaacs and Henry Francis Fynn. Despite being well treated by Shaka, they later colluded to portray him as a demonic mass-murderer to cover their own dodgy activities, stealing ivory, taking local “harems”, smuggling guns and possibly even slaves. Isaacs’ account compares Shaka to the barbarian ruler Attila the Hun, but unsupported by any solid evidence.

This image gelled nicely with pre-existing stereotypes of African savagery. And it suited colonial invaders to blame the Zulu for depopulating large areas by wiping out other “tribes” far inland, freeing up territory for colonial settlement. As the South African historian Shula Marks, among others, showed a long time ago, this “myth of the empty land” has little to recommend it. Shaka himself could only to a limited extent have been responsible. This was the basis for the phenomenon that a century later would be dubbed the “mfecane” wars. In fact, regional violence long pre-dated Shaka, and the greatest vectors were later, including slaving from Mozambique and Boer-British invasion from the south-west. Shaka by contrast was as much a haven for disturbed peoples as he was a conqueror.

Elements of the monster image still circulate, but these have largely been displaced by the opposite: the intelligent, if militaristic, statesman. In popular discourse, the most influential work has undoubtedly been South African historical writer EA Ritter’s 1950s novel Shaka Zulu. Ostensibly drawing on Zulu sources, Ritter portrayed a rather capricious, but gifted and undefeated military genius, a state-builder.

His rather lurid and pulpy novel was transformed by a ghostwriter into something that comes across as more of a history, and so it has been persistently accepted. Much of the subsequent mythology derives from Ritter: the trauma of childhood bullying, the warriors dancing on thorns, the invention of the stabbing spear, the battle tactics, many of the killings – largely made up. Shaka never loved a woman named Pampata; he never defeated the Ndwandwe at Gqokli Hill. The latter battle is cited in book after book as the prime example of his military acumen. Unfortunately, there is no evidence whatsoever that this encounter happened.

What do you hope a new TV series will contribute historically?

My impression is that producers and publishers are taking greater steps to consult historians. These include South African illustrator Luke Molver’s more level-headed graphic novels: his 2017 Shaka Rising, for example, includes an appendix noting the historical uncertainties and debates.

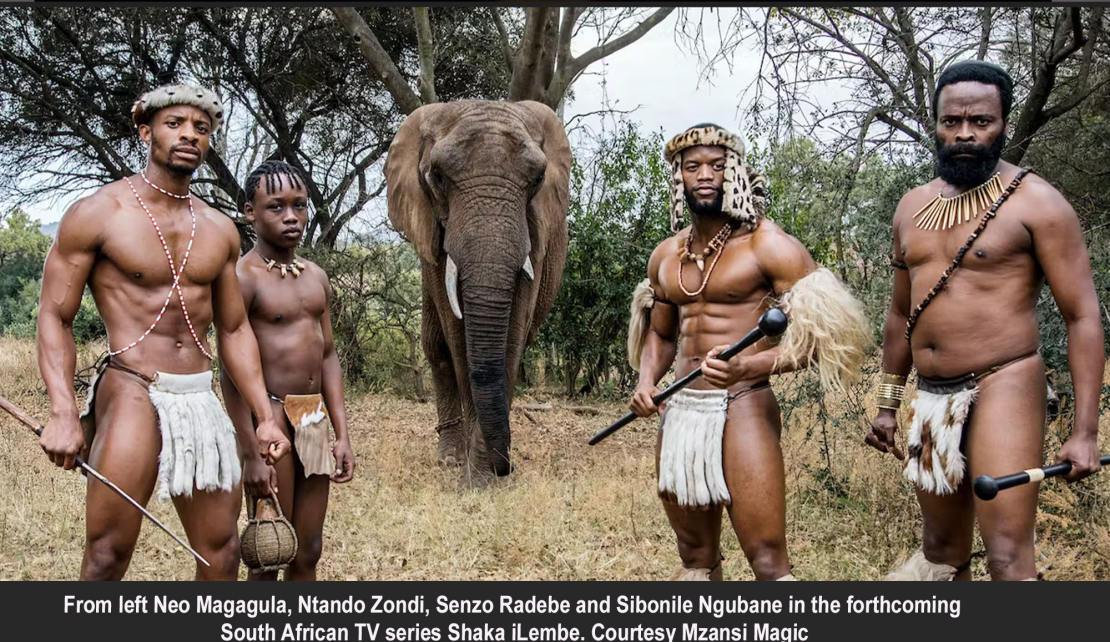

The upcoming Shaka iLembe has also made efforts to consult historians and to achieve greater authenticity. In the end, of course, storytelling will prevail over factuality – and in Shaka’s life story there are so many factual gaps or competing versions that a “story” has to be forged. That’s art.

It becomes a question of what the story implies. I’d hope that new treatments dump the dreadful, portentous stereotyping and portray Shaka more realistically.

He was, in my view, neither unrestrained mass-murderer nor superhuman conqueror, but a tough, competent leader who wielded alliances with his neighbours, absorbing people into new structures more than chasing them away. But such intricate politics don’t make for such great TV – or do they?

Shaka iLembe premieres on Mzansi Magic on DStv on 18 June

Dan Wylie, Professor of English, Rhodes University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.