AFRICA | Slavery, tax evasion, resistance: the story of 11 Africans in South America’s gold mines in the 1500s

The transatlantic slave trade was one of the most devastating and inhumane processes in human history. It is the subject of many studies, but the individual life histories of the arrival and survival of enslaved people in foreign lands remain largely untold.

A lawsuit filed against a slaver in 1589 in Antioquia (a province in today’s Colombia) allowed me to trace the paths of 11 enslaved Africans. The slaver needed to prove these Africans entered legally on ships and over land from Africa into the heart of a South American mining operation.

Their lives were extraordinarily challenging. They were captured near the Atlantic coast of Africa, by the rivers of Guinea-Bissau and Sierra Leone. One of them, Ana, was captured in the kingdom of Ndongo, in Angola, west-central Africa.

As a scholar of African history, I have dedicated my research to recovering the individual histories of these enslaved people and their cultural contributions.

My archival research in several continents has revealed antique maps, sale and criminal records, and accounts that uncover complex narratives of survival. From the 1500s to the 1800s around 12 million Africans were enslaved by Europeans and their descendants in the Americas. My recent research illuminates the experiences of 11 of them.

It challenges historical narratives that reduced enslaved populations to economic commodities and reframes our understanding of identity, resistance and agency of African people.

South American gold and enslaved Africans

The Spanish began exploring the Americas in 1492 and encountered highly advanced civilisations, including the Aztecs, Inca, Tayrona and Muisca. Despite this, they immediately sought to settle and control vast territories.

They enslaved the native population to mine metals. Yet, the indigenous Americans lacked immunity to European diseases, leading to massive population collapse. Many others died from the brutality of enslavement and European weaponry. Historians estimate that 90% to 95% of indigenous Americans died shortly after European arrival.

The abundance of American metals was matched only by European greed. Limitless demand generated the largest forced migration in world history. Africans, torn from their families and lands, were condemned to endure unimaginable conditions in the Americas.

However, they were not passive victims. Along with indigenous Americans, they continuously resisted. They rebelled, sabotaged, attacked and, most importantly, constructed new community ties and identities in the Americas.

A lawsuit from 1589

A lucky day at the General Archives of Colombia granted a crucial discovery: a detailed lawsuit from 1589. It required a slaveholder to prove the legal entry of 11 Africans to mines called Zaragoza. Deciphering this old Spanish text consumed months, but ultimately revealed incredible data about these Africans.

This was an era when even the names of enslaved people were systematically erased. My first surprise was discovering names in the document. These were not their original names, of course, but labels created by slave traders based on things like the geographical features of where they were captured.

These labels contained valuable clues about their origins. Ana Angola stood out as the only one of the group from west-central Africa. The others were from west Africa. Maria, Francisco, Pedro, Domingo and Juan shared the surname Biafara, connected to a society in today’s Guinea-Bissau. Felipa, Ana, Pedro and Pedro-Cacheu carried the surname Bran, associated with the Manjaku society from Guinea-Bissau. The lawsuit also mentioned Ximón, associated with the Sapi, originating from the Sierra Leone region.

Panning gold in Concepción

The slavers apparently disembarked the Africans in a small Panama port called Concepción. Notably, this was not an official port recognised by the Spanish monarchy, which controlled the territory at that time. The motivation was clear: by using unofficial ports, slave traders could evade taxation on enslaved people.

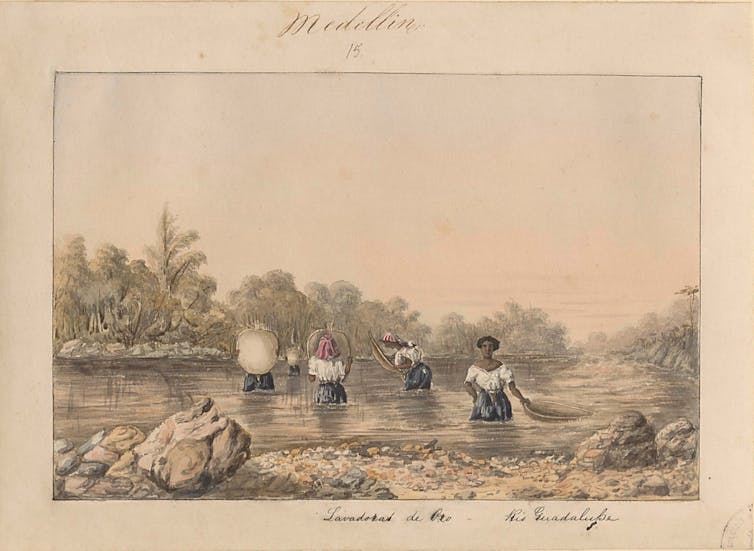

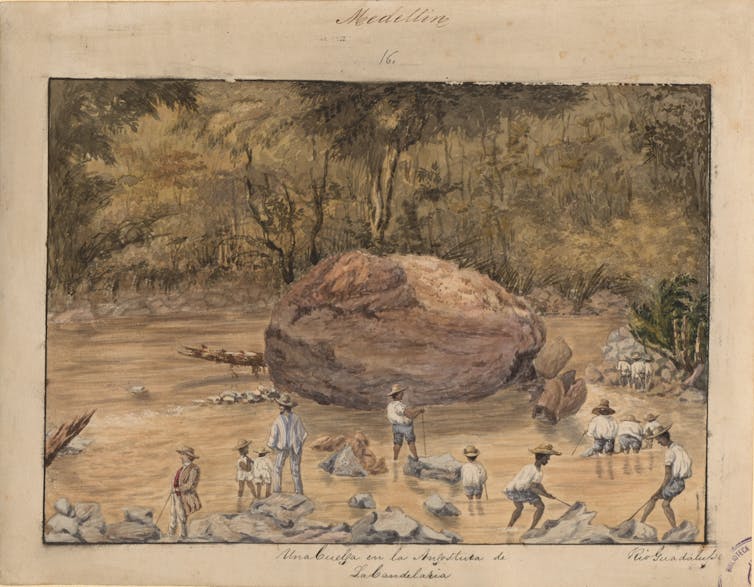

The 11 Africans worked panning gold in Concepción for about seven years in extreme conditions. They were located in a dense tropical forest amid a mood of unease. The colonial enterprise was constantly challenged by resistances from indigenous Americans and enslaved Africans who had escaped. Ana, with her distinct language and cultural background, probably struggled to form easy connections with her companions.

Then, without warning, they were forced to make another hard journey.

A journey over land

The Spanish smuggled the 11 enslaved Africans over land to Colombia, where gold was more abundant. They made several stopovers on a journey that might have lasted months, through tropical forests and over mountain ranges.

This added another layer of injustice to their story. Slave smugglers increased their profits, avoiding taxes, while enslaved Africans endured increasingly risky routes with no guarantee of basic sustenance or shelter.

Untold stories

The lawsuit doesn’t reveal whether the 11 escaped or remained in captivity in Antioquia. But, in the course of my research, I’ve found evidence of broad patterns of resistance. In the same region, other Africans had successfully escaped enslavement, establishing autonomous communities. These 11 Africans likely came close to these remarkable communities of escapees.

One 16th century chronicle noted a striking demographic reality: 3,000 Africans worked alongside 300 Spanish in the mines of Colombia at the time Ana Angola and her companions arrived. A ratio of ten to one.

This illustrates how deeply the cultures created by Africans and their descendants might have influenced this region. Countries like Panama and Colombia bear rich cultural inheritances from Africans – in food, dance, spirituality and family structures.

Reconstructing the lives of these 11 Africans allows me to reflect on how the forced journeys may have affected their lives. The long mobilities may have had an impact on the nature of their responses to slavery and the identities they created in the new social contexts of the mines.

For me, illuminating their stories is an act of liberating these African lives from silence by reclaiming their struggles and wisdom. In the process they are freed from the shadows of marginalisation and forgetting.

Paola Vargas Arana, Research Associate in African History, University of Manchester

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.