CARIBBEAN | The New Colonial Arithmetic: Caribbean Nations Caught in Washington's Deportation Dragnet

As small states accept America's unwanted, their own nationals are shipped to African prisons

KINGSTON, Jamaica, January 8, 2026 - Calvin G | WiredJa - The arithmetic of power in the Caribbean has never been subtle, but rarely has it been laid so bare. In the opening days of 2026, Antigua and Barbuda and Dominica confirmed agreements to accept third-country nationals the United States cannot—or will not—return to their countries of origin.

Guyana has entered "productive discussions" toward a similar arrangement. Meanwhile, just months earlier, a 62-year-old Jamaican man sat in an African maximum-security prison, sent there by the very same United States that now asks the Caribbean to share its deportation burden.

The irony is not lost on the region. It is simply being swallowed whole.

The Etoria Affair: Jamaica's Wake-Up Call

Orville Etoria arrived in the United States as a child. He was convicted of murder in 1997, served a 25-year sentence, and was released on parole in 2021. His debt to American society, by any reasonable measure, had been paid.

Yet in July 2025, the Trump administration shipped him not to Jamaica—his country of birth—but to Eswatini, the tiny southern African kingdom formerly known as Swaziland.

The Department of Homeland Security claimed Etoria was among criminals "so uniquely barbaric that their home countries refused to take them back." Jamaica's government flatly contradicted this, insisting it has never refused the return of any citizen.

His lawyers at the Legal Aid Society were more direct: Jamaica was willing to accept him. The US simply never asked.

For over two months, Etoria languished in Matsapha Correctional Complex—a facility notorious for holding pro-democracy activists in Africa's last absolute monarchy—without charge, without legal access, and without explanation.

He was eventually repatriated to Jamaica in September 2025, but only after international pressure mounted. Four other men from Cuba, Laos, Vietnam, and Yemen remain detained there.

The price tag for this arrangement? Eswatini's finance minister confirmed the US paid $5.1 million for the privilege of sending up to 160 deportees to his country.

The Caribbean's Turn

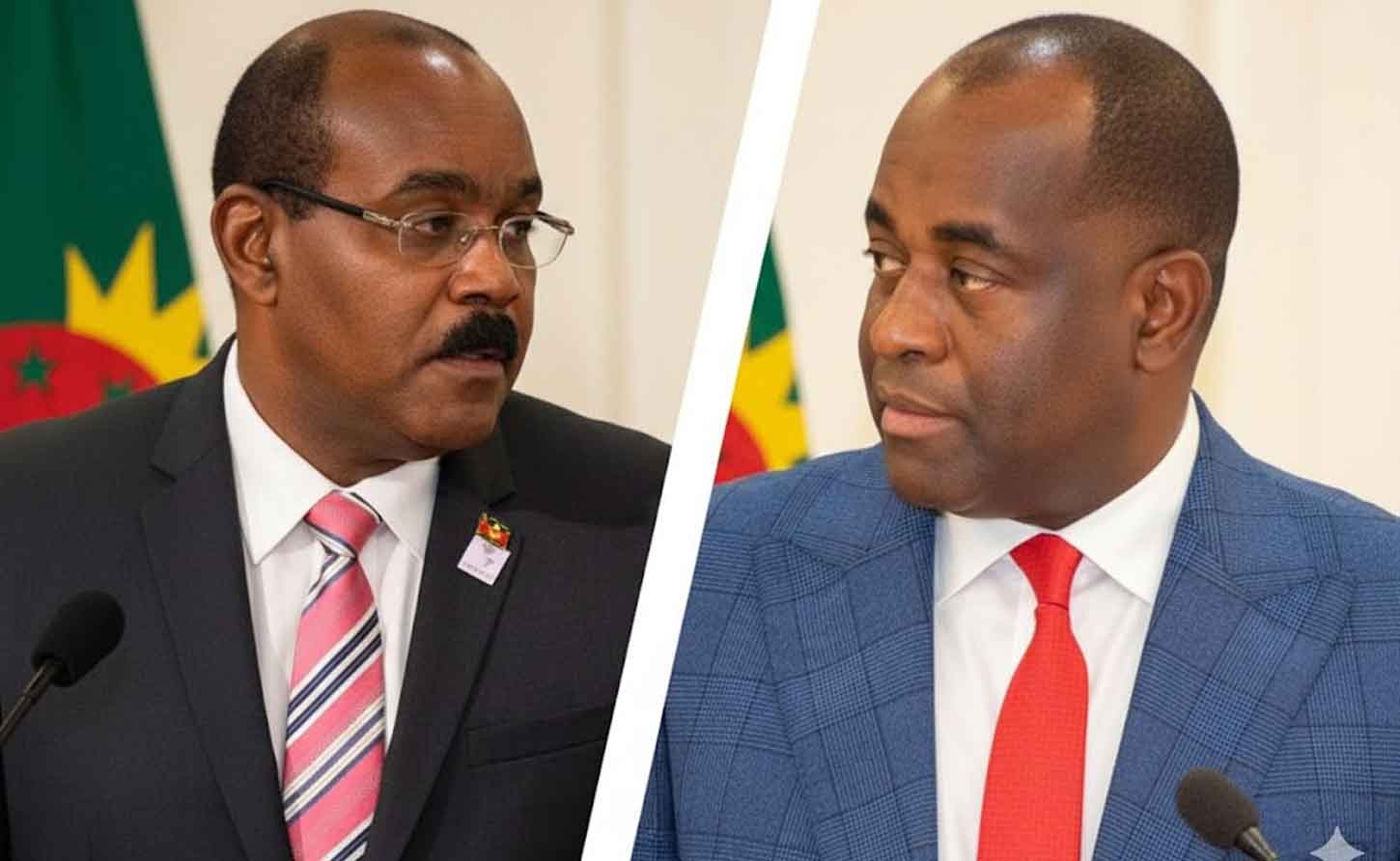

Now the script has flipped—or rather, expanded. Dominica's Prime Minister Roosevelt Skerrit announced his government has signed an agreement to accept third-country refugees from the United States.

Antigua and Barbuda's Prime Minister Gaston Browne confirmed his twin-island nation will accept up to ten "non-criminal refugees" with skills in local demand. Guyana's Foreign Secretary Robert Persaud acknowledged ongoing discussions with Washington on a framework "consistent with our national priorities."

The timing is instructive. Both Dominica and Antigua found themselves under a US travel ban imposed December 16, 2025, targeting their Citizenship by Investment programmes. The stated concern: insufficient vetting of wealthy passport buyers from Russia, China, and Iran. The unstated reality: leverage.

Skerrit explicitly tied his government's cooperation to the travel restrictions. Browne framed his agreement as "goodwill." Neither addressed the fundamental asymmetry at play—small Caribbean states with populations smaller than most American cities, negotiating under sanction with the world's most powerful nation.

The Silence of the Region

What remains conspicuous is the quiet from the rest of CARICOM. Browne noted that Washington has approached more than 100 countries to share the immigration burden, with "several" Caribbean Community members already signed on. Yet no other governments have publicly confirmed participation.

This silence speaks to a deeper fracture. The Caribbean has long prided itself on collective diplomatic strength—the principle that small states united can resist pressures that would crush them individually. The spectacle of member states negotiating bilateral deportation deals while others remain unnamed suggests that unity has its limits when Washington comes calling.

The question now echoing through the region is brutally simple: if the United States can sanction Caribbean nations into accepting its deportees while simultaneously shipping Caribbean nationals to African prisons without consultation, what sovereignty remains?

The colonial arithmetic, it seems, never really ended. It simply learned new formulas.

-30-