JAMAICA | Click, Send, Gone: How Jamaica's Banks Are Failing Fraud Victims

While billions vanish from customer accounts, regulators shrug and banks blame the very people they failed to protect

George Rivera thought he was being responsible. When the text message arrived — bearing what appeared to be NCB's branding, warning that his account had been compromised — he did what any diligent customer would do. He clicked the link. He entered his credentials. He tried to secure his money.

By the time he logged into his actual account the next day, the damage was catastrophic. His savings account, which had held $293,000, now showed a balance of sixty-seven dollars. His credit card had been charged $21,000 for petrol purchases he never made. And someone — using his identity, his account, his life — had taken out a $315,000 loan.

One click. One moment of misplaced trust. Three hundred and thirty-five thousand dollars gone.

Rivera is not alone. Across Jamaica, thousands of customers are discovering that the institutions they trusted with their money have become crime scenes — and that when the criminals finish, the banks have little interest in making victims whole.

The Scale of the Crisis

The numbers should terrify every Jamaican with a bank account.

The numbers should terrify every Jamaican with a bank account.

Total fraud losses in Jamaica's banking sector surged to $1.73 billion in the year ending March 2023 — nearly double the pre-pandemic peak. Credit card fraud alone accounted for $658 million. Debit card fraud added another $305 million. Internet banking fraud contributed $262 million. Together, digital fraud now represents seven of every ten dollars stolen from Jamaican depositors.

The trajectory is damning. In 2018, banks reported just 72 cases of internet banking fraud. By 2022, that figure had exploded to 742 — a tenfold increase in four years. The Statistical Institute of Jamaica's 2023 Crime Victimisation Survey recorded 88,108 incidents of bank and consumer fraud, a figure so staggering it suggests white-collar crime has become as prevalent as the street crimes that dominate headlines.

And these are only the cases we know about. The Major Organised Crime and Anti-Corruption Agency believes actual losses from cyber-enabled schemes exceed $1 billion — because banks, concerned about reputational damage, often prefer to quietly reimburse customers rather than file official reports. The silence protects institutions. It does nothing for victims.

The $47.5 Million Case Study

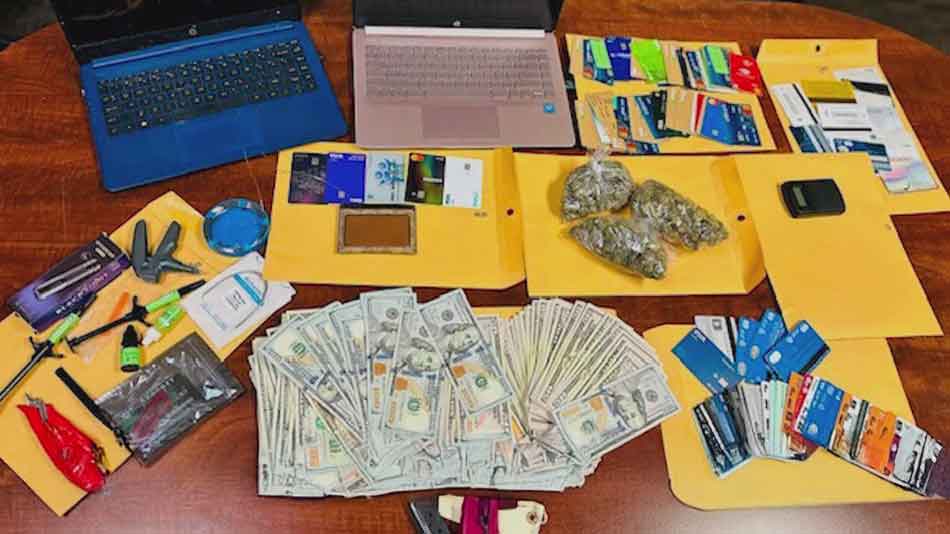

Between April and June 2022, an organised criminal syndicate executed one of Jamaica's most sophisticated phishing operations. Sixteen National Commercial Bank accounts were compromised. Over $47 million was siphoned through fraudulent transfers, then dispersed across beneficiary accounts and withdrawn before anyone could intervene.

The investigation that followed exposed something more troubling than mere criminal ingenuity. Among the dozen-plus suspects arrested by MOCA were individuals who should have been protecting Jamaicans, not robbing them.

In November 2024, authorities charged 25-year-old Garrick Lewis — a serving Jamaica Defence Force soldier — with acquisition of criminal property and related offences. A policeman was among six others charged in a separate smishing operation that targeted an elderly NCB customer, stealing US$45,000 and J$7.4 million from a single victim.

The symbolism is impossible to ignore. The same security forces entrusted with defending citizens were allegedly embedded in syndicates designed to fleece them. If soldiers and police officers are complicit in banking fraud, what confidence can ordinary Jamaicans have in the systems meant to protect their savings?

The Consumer Protection Vacuum

The Consumer Protection Vacuum

When Deputy Governor of the Bank of Jamaica Dr. Jide Lewis appeared before a parliamentary committee in 2024, his response to the fraud epidemic was remarkable for its candour — and its inadequacy.

While acknowledging that the losses were "extremely regrettable," Lewis offered perspective that must have chilled every depositor listening: fraud, he explained, is "just a part of the operational risk that a commercial bank undertakes when it decides to go into this business."

There it was — the regulatory philosophy laid bare. Fraud is not a crisis to be eliminated. It is a cost of doing business, to be managed within acceptable parameters.

The BOJ's own submissions reveal the structural problem. Under current supervisory frameworks, the central bank's primary concern is the "safety and soundness of deposit-taking institutions" — meaning the focus is on whether fraud threatens banks' capital reserves, not whether it devastates individual customers. Consumer protection is, at best, an afterthought.

The data confirms this. In 2022, three-quarters of fraud complaints filed with the BOJ were resolved. By 2023, that figure had dropped to two-thirds. Fraud cases, the BOJ explains, "often involve police investigations, which take time to complete." Meanwhile, victims wait — for answers, for reimbursement, for acknowledgment that their institutions failed them.

Deputy Commissioner of Police Fitz Bailey testified that NCB and Scotiabank alone accounted for 85 percent of the 601 fraud reports police received between 2022 and early 2024. Yet these same institutions continue operating without meaningful regulatory sanction, their licences unchallenged, their executives unaccountable.

The Blame Game

Perhaps most galling is the industry's response to its own failures.

Perhaps most galling is the industry's response to its own failures.

Dane Nicholson, chairman of the Jamaica Bankers Association's anti-fraud committee, told the Sunday Gleaner that banks would need to "put measures in place to protect customers from themselves because some customers are still inadvertently exposing themselves to these types of activities."

Read that again. Customers are "exposing themselves." The burden falls on the grandmother in Junction who clicked a convincing link, not on the billion-dollar institution that failed to implement adequate authentication protocols.

NCB's solution to the smishing epidemic was instructive: in October 2023, the bank simply suspended SMS transaction alerts entirely. Rather than secure their messaging systems or implement verification measures, they eliminated the service. Problem solved — for the bank. Customers lost a critical fraud-detection tool because NCB could not be bothered to protect it.

The refrain is consistent across the sector: customers must be the "first line of defence." Banks spend millions on advertising campaigns warning Jamaicans not to click suspicious links, not to share passwords, not to trust unsolicited calls. What they spend far less on is accountability when their own systems — legacy POS terminals with vulnerabilities dating to the 1980s, inadequate authentication protocols, insufficient transaction monitoring — enable the fraud in the first place.

The Reckoning

The question Jamaica must answer is not whether fraud will continue — it will. The question is whether depositors will remain collateral damage in a system designed to protect institutional balance sheets rather than individual citizens.

When a JDF soldier can join a fraud syndicate, when $400 million can vanish through offline POS terminals exploiting decades-old vulnerabilities, when the central bank's deputy governor describes billion-dollar losses as acceptable "operational risk" — something fundamental has broken.

Jamaican depositors deserve a regulatory framework that prioritises their protection, not one that treats their losses as an accounting inconvenience. They deserve banks that invest in security rather than blame-shifting. They deserve accountability when institutions fail.

Until then, every text message is a threat. Every click is a gamble. And every depositor is on their own.

-30-