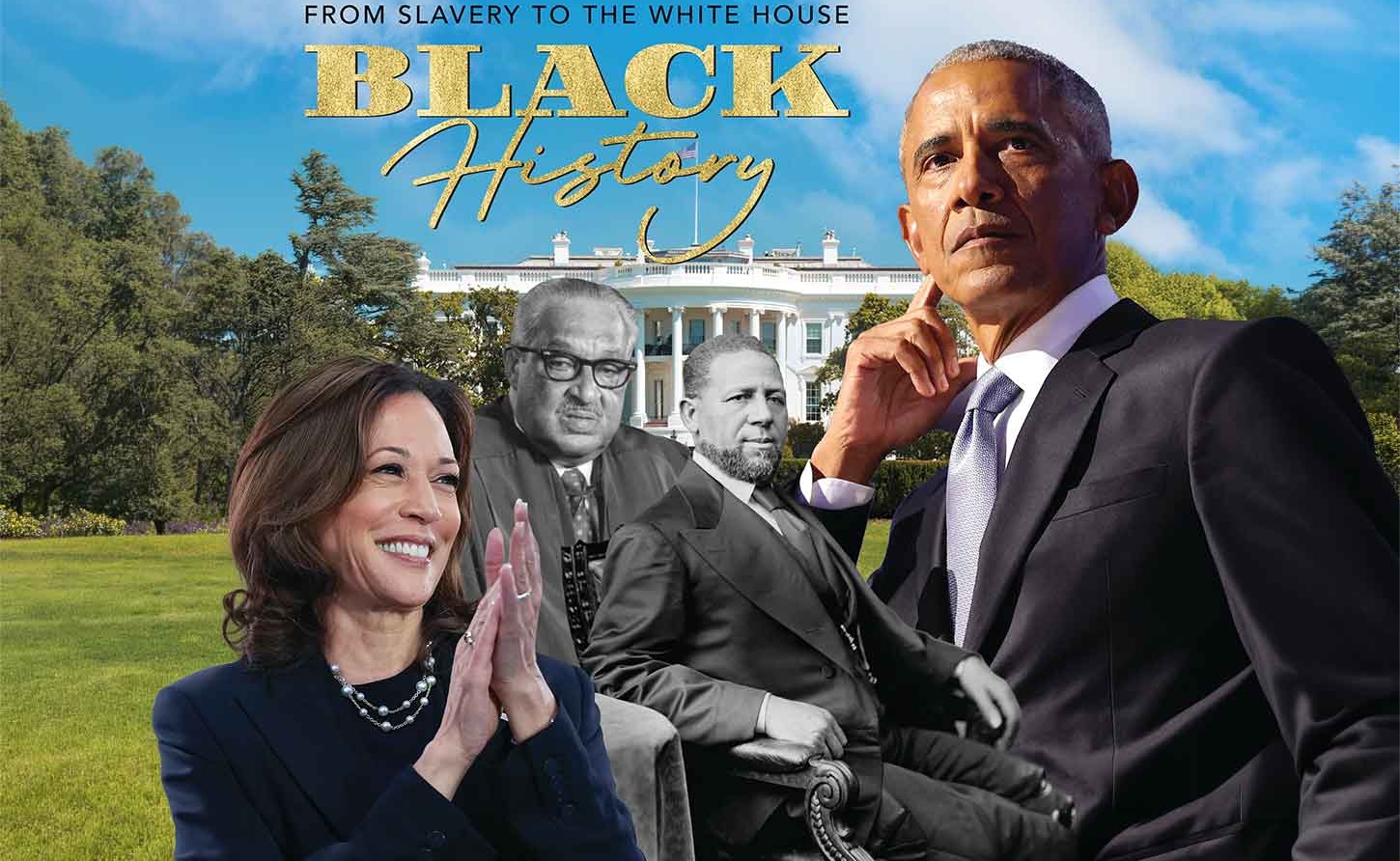

CULTURE | A Month's Celebration for $100 Trillion in Unpaid Black Labor They Refuse to Acknowledge

By Calvin G. Brown

MONTEGO BAY, Jamaica, February 8, 2026 - Between $100 trillion and $131 trillion. That is what the Brattle Group—an internationally recognized consortium of expert economists—calculated as the reparations owed for transatlantic chattel slavery. One hundred trillion dollars.

To put that in perspective, it exceeds the current GDP of the United States, the United Kingdom, and every former slaveholding European nation combined. Yet America asks Black people to celebrate their history in twenty-eight days. February. The shortest month of the year.

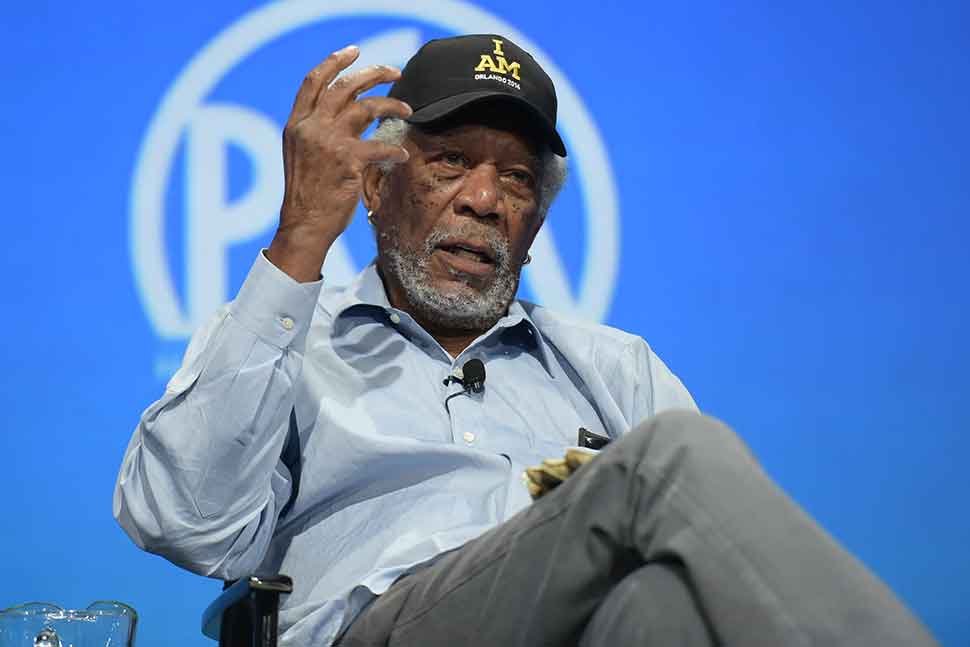

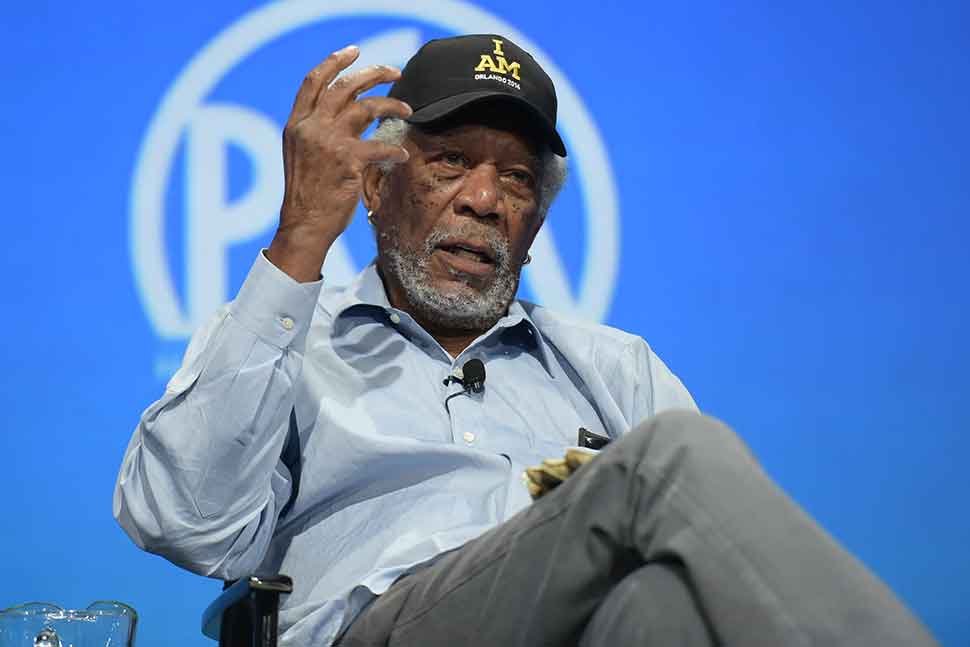

Morgan Freeman was not mincing words when he called it an insult. In multiple interviews spanning nearly two decades, the Academy Award winner has maintained the same position: You are going to relegate my history to a month?

Black history is American history. He is right. And the Brattle Group's meticulously researched 2023 report—commissioned by the University of the West Indies and the American Society of International Law—provides the irrefutable mathematical proof: when a people's unpaid labor built an entire nation's economic foundation to the tune of over $100 trillion, calling their story Black History rather than American History is not just inaccurate. It is calculated erasure.

The Numbers Don't Lie: America's $100 Trillion Debt

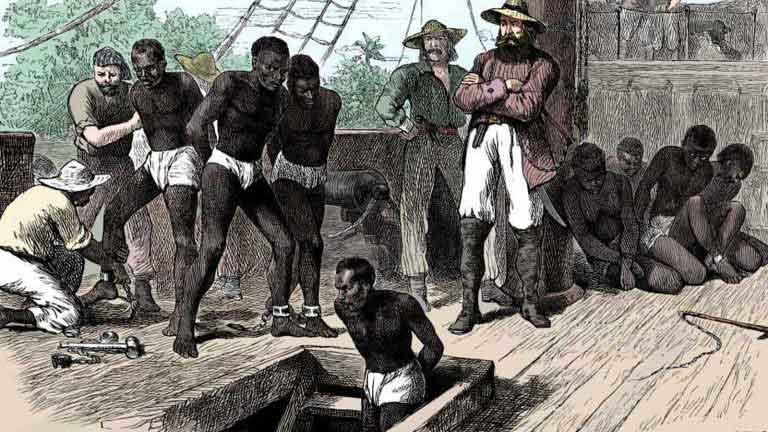

This covers stolen labor, lost lives, loss of liberty, gender-based violence including systematic rape and forced pregnancy, personal injury, and mental anguish. But that is only half the story.

Post-enslavement continuing harms—Jim Crow laws, systemic racism, wealth disparity that persists to this day—add another $22.9 trillion to the ledger. The United States alone owes $26.8 trillion just for its direct practice of slavery.

Britain owes $24 trillion, with $9.6 trillion specifically owed to Jamaica. Spain owes $17.1 trillion. Portugal, $20.6 trillion. The aggregate total across all former slaveholding nations: $107.8 trillion.

What did this astronomical sum build? Everything. Enslaved Black labor produced cotton, tobacco, rice, and sugar valued at over half of America's antebellum gross domestic product.

They built the US Capitol. They built the White House. They built universities, churches, and the profitable landscapes that made plantation owners wealthy beyond measure.

Northern industry—textile mills in Massachusetts, shipping operations in New York, banking and insurance companies in Boston—enriched themselves on crops picked by Black hands under the lash.

The National Museum of African American History and Culture states it plainly: The lives and labor of enslaved African Americans transformed the United States into a world power.

Not contributed to that transformation. Transformed. There is no conditional tense here, no qualifier suggesting a supporting role. Black people did not help build America. They built it. With their bodies, their blood, their stolen children, their unpaid labor across two and a half centuries.

Here is the uncomfortable truth that Black History Month obscures: this is not GDP for one year. This is the accumulated value of centuries of forced labor that created America's entire economic infrastructure.

When we teach American history—westward expansion, the Industrial Revolution, the rise of American capitalism—we are teaching Black history. There is no separation. The foundation and the structure are one.

Beyond Economics: Innovation Erased

The Brattle Group's $100 trillion calculation addresses only economic damages. It cannot capture the full scope of what was stolen—including intellectual contributions that powered America's technological supremacy.

The Brattle Group's $100 trillion calculation addresses only economic damages. It cannot capture the full scope of what was stolen—including intellectual contributions that powered America's technological supremacy.

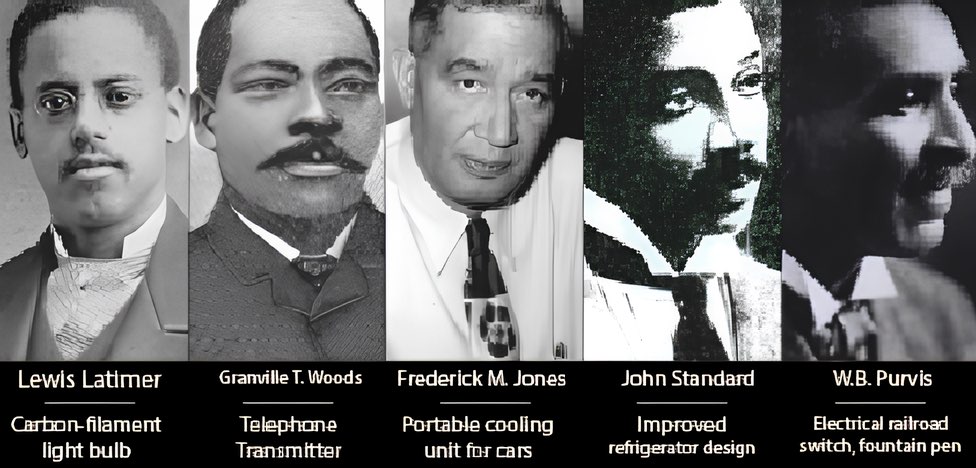

During the so-called Golden Age of Invention from 1870 to 1940, Black Americans secured over 50,000 patents. That represents 2.7 percent of all United States patents during that period—more than nearly every immigrant group except those from England and Germany.

Consider Lewis Latimer, son of escaped enslaved people, who became a leading electronics engineer. He made technical drawings for Alexander Graham Bell's telephone and worked with Thomas Edison improving electric lighting systems.

Granville Woods, dubbed the Black Edison, revolutionized railway communication with his multiplex telegraph, allowing moving trains to communicate with each other and stations—a fundamental safety innovation. Garrett Morgan invented the three-position traffic signal that still governs our streets and the gas mask that saved thousands of lives in World War I.

The innovation did not stop. Valarie Thomas invented 3D imaging technology while working at NASA. Mark Dean co-invented the IBM personal computer and holds twenty patents. James West's foil electret microphone is used in ninety percent of modern microphones—every phone call, every recording, every voice assistant relies on his invention.

Then, there is David Blackwell, the Black man who was a renowned American statistician and mathematician known for his foundational contributions to game theory, probability theory, information theory, and statistics. He was the first African American scholar to be inducted into the National Academy of Sciences and laid the foundation for artificial intelligence. Last year Nvidia named their chip after Blackwell.

These are not footnotes to American technological history. They are central chapters, hidden in plain sight.

And here is the devastating truth that Brookings Institution research reveals: discrimination suppressed even more innovation. How many potential inventors never got the education they deserved?

How many brilliant minds were denied access to laboratories, universities, research funding? How many patents were stolen by white lawyers who worked with Black inventors? The 50,000 patents we know about represent a fraction of what Black Americans could have contributed in a just society.

Morgan Freeman was not mincing words when he called it an insult. You are going to relegate my history to a month? The United States alone owes $26.8 trillion just for its direct practice of slavery.The Paradox of Separation

Morgan Freeman was not mincing words when he called it an insult. You are going to relegate my history to a month? The United States alone owes $26.8 trillion just for its direct practice of slavery.The Paradox of Separation

In 1926, historian Carter G. Woodson established Negro History Week. He hoped it would eventually end—that it would become unnecessary once Black history became fundamental to how America taught its own story. One hundred years later, not only has it not ended, it has expanded to an entire month. This expansion is not progress. It is proof that the mission failed spectacularly.

Morgan Freeman understands the cruel irony. By segregating Black history into February—the shortest month, no less—America perpetuates the very exclusion the observance was designed to remedy. It allows the nation to quarantine uncomfortable truths for twenty-eight days, then return to a sanitized narrative that erases Black people from the story of America's rise.

The Brattle Group's findings on post-enslavement damages reveal why this segregation persists. The $22.9 trillion in continuing harms is not ancient history—it is the accumulated cost of discrimination that never stopped.

For one hundred years after the Emancipation Proclamation, Jim Crow laws enforced racial apartheid across the American South. Nearly 4,400 Black people were lynched, often with the tacit approval or active participation of law enforcement.

In 1921, white mobs—some deputized by city officials—burned Tulsa's Black Wall Street to the ground, destroying what was then the wealthiest Black community in America.

Slavery did not end with the Thirteenth Amendment. It morphed. It adapted. Black Codes forced formerly enslaved people back onto the same plantations under different terms.

Convict leasing turned arrest into re-enslavement. Redlining denied Black families wealth-building through homeownership. The GI Bill, theoretically race-neutral, was administered in ways that excluded Black veterans from benefits their white counterparts received freely.

George Floyd, murdered on camera as a white police officer knelt on his neck for nine minutes. Tyre Nichols, beaten to death by five Black police officers so thoroughly indoctrinated into anti-Black policing that they saw a Black man and responded with lethal force.

These are not aberrations. They are the $22.9 trillion made flesh—the quantifiable proof that the discriminatory treatment defining chattel slavery never actually ended.

“ The lie is this: that Black history is somehow separate from American history. That it can be contained, commemorated, and then concluded when March arrives. That a month of celebration absolves a nation from the harder work of actually teaching the truth. ”

Black History Month exists precisely because America refuses to teach what the Brattle report proves with mathematical certainty: Black people did not just contribute to American development.

They were American development. Every dollar of that $100 trillion was extracted through violence, rape, family separation, and the complete negation of Black humanity. And when legal slavery finally ended, the theft simply continued under new names.

The Month That Proves the Lie

When $100 trillion in forced labor builds a nation's economic foundation, when 50,000 patents drive its technological revolution, when every major American achievement bears Black fingerprints, then Black History Month becomes what it truly is: a twenty-eight-day monument to America's most enduring lie.

The lie is this: that Black history is somehow separate from American history. That it can be contained, commemorated, and then concluded when March arrives. That a month of celebration absolves a nation from the harder work of actually teaching the truth.

Morgan Freeman is right, but perhaps not completely. Black History Month cannot simply be abolished—that would be yet another erasure. Instead, it must succeed in Woodson's original vision by making itself obsolete.

True reparation is not just the $100 trillion owed in economic damages. It is educational. It is confronting the fact that there would be no American history to teach without Black people building it, innovating it, and surviving it.

Until every American history textbook acknowledges that the foundation and the structure are one—that American history is Black history and Black history is American history—February will remain exactly what it is: the shortest month carrying the longest debt, a calculated footnote desperately pretending it is not the entire story.

-30-