JAMAICA | The Sam Sharpe War 0f 1831/32, The 'last straw' in the abolition of Slavery

MONTEGO BAY September 21, 2022 - Turning more directly and expansively to the Sam Sharpe War, often referred to as a rebellion, Its processes and its consequences, the misinformation about the Sam Sharpe War itself was numerous.

One thing on which some chroniclers seem to agree is that he was an educated Town Slave but since there was no specific period ever mentioned when and where he was a Town slave the situation has only left readers in a state of more confusion and bewilderment.

The continued ‘bending' of the history as it relates to enslaved people, had the rebellion listed as a Baptist war, even when the empirical evidence absolutely and conclusively does not support such a claim.

So what are the facts? Following Sharpe's instructions, preparation for the protest was combined with religious meetings. Large numbers of slaves met at twenty-two various established Christian churches (11 Baptists, 3 Presbyterians,3 Wesleyan Methodist, and 5 Moravians) and at an unknown number of Myal chapel locations. An Estimated 60000 persons participated in the Revolution.

Many of Sharpe’s lieutenants were not Baptists. Many were Methodist Creole (mixed race) slaves who were headmen on estates and who mortally hated the full blooded Africans. They joined in for the second time in the history of over two hundred years of slave rebellions.

The first time was the 1776 rebellion believed to be inspired by the American war of Independence.

Charged as it were with anti English sentiments, hundreds of free Blacks with no attachment to a religious denomination also participated in the 1831 rebellion, even a white sailor.

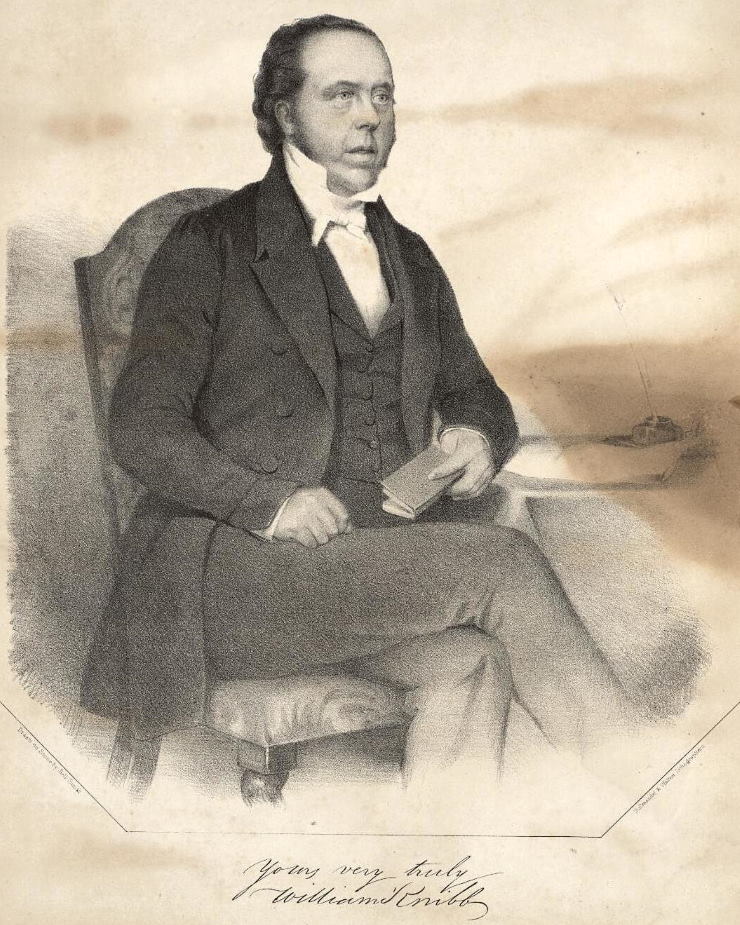

The missionaries including William Knibb, while publicly appearing to be against slavery, were not in favour of the planned rebellion as a method to end slavery. Instead Knibb urged the slaves not to rebel, but to wait on the Lord, and await Divine Providence.

Because of Knibb’s stance on the matter, he clashed bitterly with Slaves at the dedication of the new Salters Hill Baptist Church on December 27, 1831. It is alleged that he threatened to expel those persons who chose to participate in the impending rebel action from the Church,

The congregation became incensed. They began to shout at Knibb calling him uncomplimentary names such as ‘madman.’ They questioned whose side he was on, as they walked out on him at the newly dedicated Salters Hill Baptist Church.

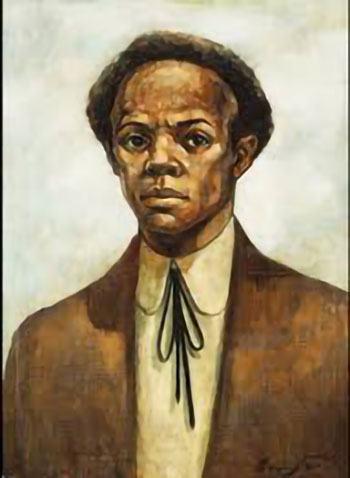

Sam Sharpe was born in 1801 and grew up to be a teenager at the Coopers Hill property now overlooking Jarrett Park and a stone’s throw from the Calvary Baptist Church located on Corinaldi ave.

He had moved from the grass gang into the great house as a domestic slave at an early age and was taught to read and write and to receive and entertain his master’s and mistress’ guests.

His master Samuel Sharpe Jr. instructed the driver on the estate, Bigga, to teach Sam how to ride the horse so he could be sent on errands.

Problems between his master and himself erupted when, in a private meeting, his master informed him he would be sold to a woman operating a guesthouse called the Stag on Strand Street which was then the MoBay waterfront, but he would not give up ownership of him.

His master warned him not to mention their private talk to anyone. Sam was Sold. As time passed he was again sold to the owner of Croydon plantation, T.G Grey Esq, near Catadupa.

Sam’s mother, Mimba, who was a slave at Coopers Hill under His master’s father Sam Sharpe (snr), and who willed Sam Sharpe the slave to the Sharpe family, was sold from Coppers Hill before her son was sold.

She was firstly a cook then head of the Jobbers Gang. That is the slave gang that the master would hire out to work on other plantations which were short of labour.

In one of her secret nightly visits to the estate to see her son, Mimba reminded Samuel that she is a big woman, and he should not worry for her as she can take care of herself. They hugged warmly and shared a tearful departure.

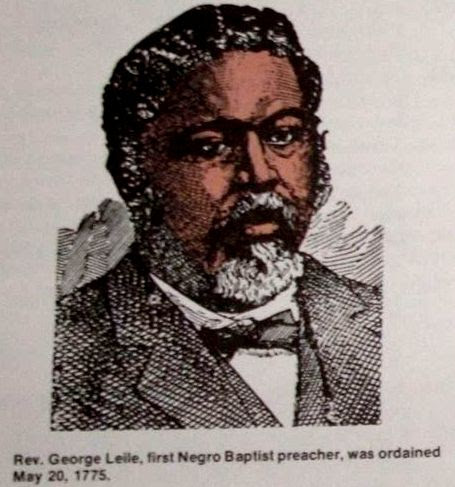

Dove and Gardiner who were later to become two of Sharpe’s lieutenants were his fellow slaves at Cooper’s Hill. All three decided to borrow two horses from the property at Coopers hill and attend Baptist preacher Moses Baker church at Crooked Spring near Black Shop/ Sunderland.

At the religious meeting he met Moses Baker for the first time and would later come under his tutelage and influence.

Also of significance, he met a beautiful young lady named Nyami from Content Estate above Long Hill. ‘Nyami’ is the female Sky God of the Tonga People living in the Zambezi River Valley between Zambia and Zimbabwe.

She later bore him a daughter whom both agreed her African ancestral name would be Ruba which in Arabic means “green Hills”. It is timely to mention here that it was also at Moses Baker's church in January 1824 That Thomas Burchell and Sam Sharpe met for the first time.

The plan for the industrial action by the enslaved Africans just after the Christmas holidays in 1831, was that after the 27th of December the slaves would refuse to work until there was a commitment from the plantation owners that they would be paid.

However, if the planters refused to give the assurance that the slaves would begin to receive wages, any attempt to force them to go back to work would be met with insurrection.

By nightfall, and with news spreading of the disastrous Salters Hill Church meeting earlier that day with Rev. Knibb, the tension and an atmosphere of confrontation had reached its peak.

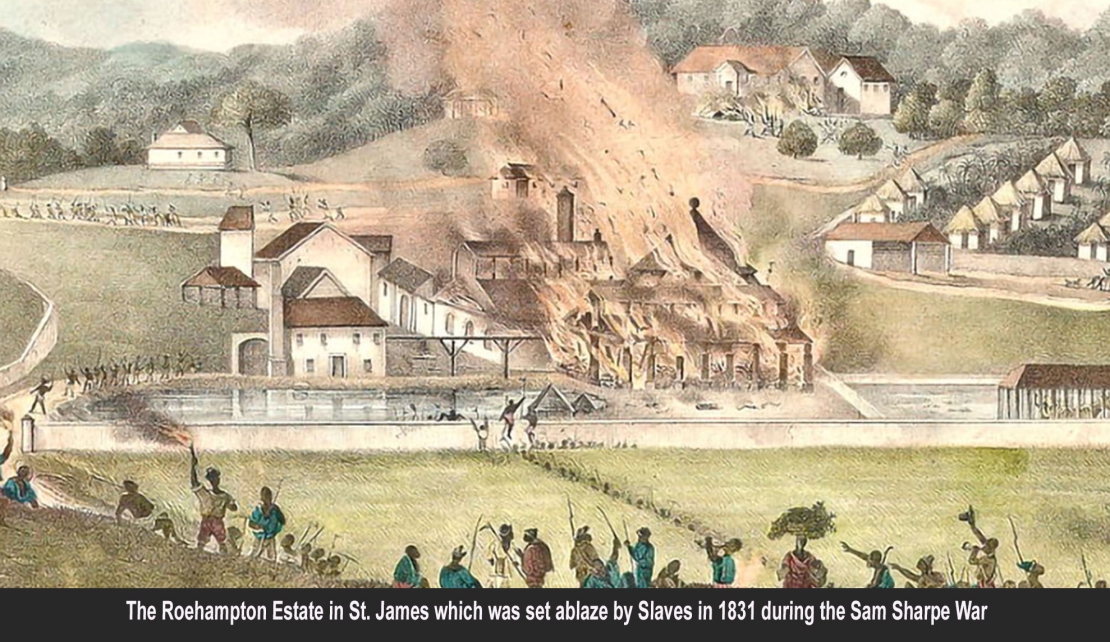

In response, the trash house was lit and triggered the eruption of numerous fires across western Jamaica, the unmistakable signal to begin the war they had spent months planning for .

The late historian Don Carter Henry who until his death lived at Kensington, in his book, “Flames of Freedom,” said on the night of December 27, 1831, when it became obvious that the planters were not relenting, the Kensington estate was set on fire by an enslaved girl (now known as a ‘Fiyah’) who lamented that “I know that I will die for this, but my children shall be free,” before setting fire to the trash house which started the conflagration. The Emancipation War had begun.

My research tells me, that night, at the Start of the 1831/32 Emancipation Rebellion, when Kensington torch of freedom was lit to signal the start of the final Slave Rebellion before Emancipation, Palmyra to the East Saluted! Then Falmouth Trelawny Responded! In this Rebellion when it started 900 great houses were in Jamaica when it ended only 15 remained.

It was a slave known as John Dunbar was the person who arranged for the thrash house at Tulloch Castle Estates to be set afire and started the 1831/32 slave rebellion. “He would not have been chosen for such a huge task to send the first fire signal across western Jamaica had he been a wishy washy and flippant individual. So what was he?.

Kensington Estates, like all other large estates, had its own slave hospital and armoury. “John Dunbar was the resident doctor (medicine man or myalist) at that hospital. Medicine men along with the priest or “Bongo Men” of the “Convince Cult” were the healers among the slave society and even some of the white society that would privately seek their assistance.”

“Sam Sharpe and his lieutenants chose a man, John Dunbar who was respected both in the white society and the slave society ... a man of cool demeanor and an ardent Christian at the Salters Hill Baptist Church. The plan was if there were attempts by the authorities to force slaves to go to work again as slaves, then the rebellion should begin.”

There is an argument that when the waring company of Black rebels had the upper hand and they converged at Long Hill, their failure to take over Montego Bay was due to the time they spent arguing among themselves as to who should be crowned king! This was outright rubbish!

The rebellion was about ending slavery it was not to set up a Haiti type Government in MoBay or Jamaica. Secondly If there was ever any thought about crowning a king in Montego Bay, why should the Rebels be arguing about who would be King when their acknowledged leader Sam Sharpe was very much alive and well and leading the charge?

So, what are the facts? Because of the clash at Belvedere and Montpelier estates, Colonel W.S. Grignon, head of the St. James and the combined interior western militia was out maneuvered by the Black Regiment of Sharpe’s men.

The rebels on reaching Long Hill had a clear view of what was happening in the harbor. They receiving intelligence by way of “Bush Telegram,'' and decided that they could not, with a few guns, match the firepower of the three British Man O'Wars in the Montego Bay harbor.

Any attempt to confront the three British warships with cannons and thousands of soldiers consisting of artillerymen with field guns with mortars and with rocket launchers, would be suicidal!

In any case both Captain Charles Williams of the HMS Sparrowhawk and General Sir Willoughby Cotton, commander of the British forces In Jamaica and the HMS Racehorse, concurred in their report that the plan of the Rebels was to burn down Montego Bay and therefore not to crown a King!

At this point in the conflict, the Rebels changed strategy and began to focus on the destruction of the physical infrastructure, the very foundation of plantocratic slavery: wharves, water canals and factories. One Hundred wharves were destroyed around the country according to the Governor in a report to the secretary for the colonies.

Within 10 days, the Sam Sharpe War was over but its impact was monumental. It had the effect of countering the rumour by the West India Lobby, comprised of absentee landowners and powerful London Merchants, who claimed that slaves in Jamaica did not want slavery to be abolished as they would be very unhappy if they were not owned by anyone!

The Rebellion also strengthened the hands of the members of the anti-slavery society to whip up more public opinion against slavery. A sectarian war of sorts emerged between the established Anglican Church and the non-conformist churches, marking a second but different phase of hostilities.

The Anglicans, the church of the planters, accused the leadership of non-conformist churches of influencing the slave to rebel and detained the Reverend Mr. Knibb, Burchell, in addition to six others across Jamaica.

With the exception of the Moravian minister in Mandeville, The Reverend Mr. Pfeiffer, none of those named were charged with any crime and were at liberty to carry on their work.

A national organization called the Colonial Church Union (CCU) equivalent to klu klux klan in the USA, was formed in the Parish of St. Ann with chapters all over Jamaica, except Kingston, where the free Blacks and Coloureds would not allow it to take root.

The leader was the Reverend A.W. Bridges the Rector for the St Ann's Bay Anglican Church. The organization comprised Planters, Priests, Members of the Militia and French Royalist Whites who escaped from the Toussaint/Buckman Haitian Revolution by settling in Jamaica.

The Colonial Church Union Manifesto read in part:”The vermins (referring to the pastors of the non conformist churches), want to reduce property to dust and secure for themselves advantages that will accumulate wealth and power but it was the intention of the Colonial Church Union to wipe the non-conformist preachers off the face of the earth.”

Burning and breaking down of non-conformist churches went apace and slaves were shot on sight by the Pastors and Planters of the CCU. Several Anglican Churches were closed for worship. This included the Mandeville Parish Church, as the church buildings were turned into Military barracks and jails.

The ‘Lima Massacre’ in St James, in which two hundred defenseless enslaved Africans were rounded up and shot in cold blood in the square just outside Adelphi in St. James, is a major blot on our history.

Also referred to as The Infamy at Lima, the enslaved Africans were taken to the Lima Square - men, women and children - They were lined up by the British Militia and shot to death.

During the conflagration, the Adelphi Anglican Church was transformed into a military barracks and a jail to fight the slaves in that area. The reprisal on the slaves at Lima was launched from the church.

This must not be forgotten and deserves the erection of a memorial to the sacrifice of our ancestors and the insensitivity of the white planters to slaves as humans rather and a valuable commodity that can be disposed of on suspicion of involvement in the ‘rebellion.’

The mass murder was sanitized and recorded in the historical archives as the “Infamy of Lima” by the cast of all white historians.

While all this carnage and destruction by the Colonial Church Union was going on, according to one of many versions of this story, the Rev William Knibb and Thomas Burchell and their families who were away in England during the thick of the Rebellion returned at the extreme tail end of hostilities.

Knibb had left for England shortly after the Salters Hill Baptist Church debacle and the Rev. Thomas Burchell was in England close to 8 months before the rebellion.

They were taken off the passenger ship on which they arrived at Falmouth, by soldiers, transported by boat and were safely ensconced at sea as white British Citizens on a British warship The HMS Blanche in the Montego Bay harbour.

There were no tar nor feathers on either Mrs Knibb nor Mrs Burchell when they arrived on the warship and into safety having just returned from England. What came out in the subsequent documents of two enquiries launched by the British Government is that there was harassment and threats against the lives of Missionaries to include the Methodists, Moravians, Presbyterians, Baptists and their families.

In every case, free blacks and some whites moved to their rescue. Another reason there was no Baptist war, no Moravian war, no Presbyterian War and no Methodist War, was that most missionaries were either on the run, underground or locked away for safekeeping.

It was a Slave inspired and directed War, the biggest in terms of groupings, participation and of geographical spread in terms of absolute numbers since the 1673 rebellion in St Ann.

But curiously and peculiarly it was Bleby who regularly visited with Sam Sharpe in jail after he turned himself in. And although Sharpe had very strong suspicions about his motives, Sharpe used Him to deliver his letters including one to the British House of Commons.

The Reverend Mr. Bleby wrote some ten books, all published in london. These included: ”Josiah the Maimed Fugitive,” a true tale; Capture of the Pirates; Stories of the Western Seas;Death Struggle of Slavery;Female Heroism and Tales of the Western World; Missionary Fathers Tale; Scene on the Caribbean sea, etc.

I tracked the Reverend Bleby’s activities and found him in 1858 doing speaking engagements at the Massechucetts Anti- Slavery Society, where he was billed as a Methodist Minister from Barbados. His topic was the Christmas Rebellion of 1831 of which as the speaker, he was an eyewitness.

In June 1866, the year following the Morant Bay Rebellion, the Gleaner reported that the Rev. Henry Bleby was on the lecture circuit delivering a series of lectures in Berbice, Demerara and Essequibo Regions which are now parts of modern day Guyana, and his fees were not cheap.

On His first visit to Sam Sharpe in Jail he urged Him to write the story of his life and this Sam Sharpe did for over three months.

This is an excerpt from the letter Sam Sharpe wrote from jail to the British Parliament and asking his mistress Mrs. Sharpe to publish it or between Reverend Bleby and Mrs. Sharpe, to deliver that letter to the people it is intended for:

”The beast of the earth, the asses, the cows, the pigs, do not receive the harshness of treatment that we do. Even though we are all the property of the landowner the animals in the pens are treated with more respect. Their heads are not cut from their bodies and hang upon poles they are not flogged until they bleed, buckets of salt are not thrown on their open wounds.

They are not bound in chains and placed in stocks. To hold another in chain is against the laws of god. I learn from my Bible that the whites had no more rights to hold black people in slavery than the blacks had to make white people slaves and for my own part I would rather die than live in slavery”!!!.

The choice of place for hanging in the Albert Market of the Rt. Excellent Samuel Sharpe National Hero and the manner of his burial by the Sea has powerful symbolisms. But If we can come to an acceptance that history should not be viewed in a straight line from one date to the next but ought to be seen as a network of interlocking Dynamics coming together and impacting on one another.

And that by paying patient, consistent and forensic attention following the leads by ferreting and cross checking information is the only way to get to the facts and the truth of the matter.

On May 23, 1832, a proud and defiant Sam Sharpe was publicly hanged in the Montego Bay Square, that now bears his name, fulfilling words he uttered: “I would rather die on yonder gallows than live one more day of slavery”. He had accepted death on the scaffold as freedom from the unbearable and repugnant miseries of slavery and as the only means by which freedom was attainable.

-30-