AFRICA | Sudan's Inferno: UN Reveals a "War of Atrocities" as the World's Forgotten Crisis Burns

DARFUR SUDAN | September 23, 2025 - In a mosque in El Fasher, 75 worshippers knelt for morning prayers on a Friday in September 2025. They never rose again. The drone strike that obliterated them barely registered in international headlines—just another statistic in what the United Nations now calls "a war of atrocities" that has transformed Sudan into the world's worst humanitarian catastrophe.

As the conflict grinds into its third year, the numbers defy comprehension: over 150,000 dead, 14.3 million displaced, and 30 million people—two-thirds of Sudan's population—in desperate need of humanitarian assistance. The UN Independent International Fact-Finding Mission has documented a systematic campaign of horror where civilians are not collateral damage but deliberate targets.

For those in the Caribbean who understand the trauma of forced displacement—from the Middle Passage to contemporary climate migration—Sudan's agony resonates with particular force. This is not merely an African tragedy; it's a testament to how quickly post-colonial nations can descend into darkness when international systems fail them, a cautionary tale that echoes from Port-au-Prince to Port Sudan.

The UN's September 2025 report reads like a catalog of humanity's darkest impulses. Both the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF) and the Rapid Support Forces (RSF) have committed large-scale human rights and international humanitarian law violations, but it is the deliberate, systematic nature of these crimes that chills investigators.

The UN's September 2025 report reads like a catalog of humanity's darkest impulses. Both the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF) and the Rapid Support Forces (RSF) have committed large-scale human rights and international humanitarian law violations, but it is the deliberate, systematic nature of these crimes that chills investigators.

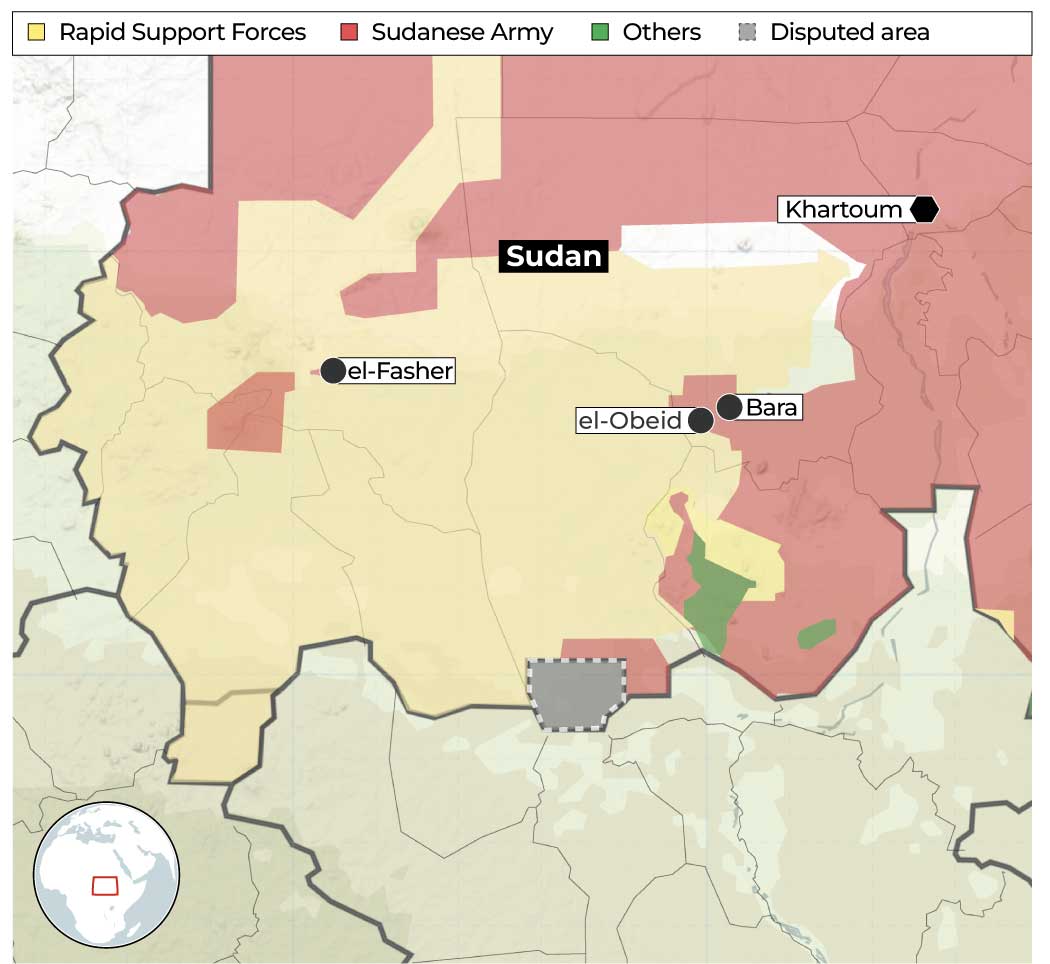

RSF detention centers have been described by survivors as "slaughterhouses" where detainees are beaten to death and summarily executed, while others are subjected to forced labor or held for ransom. The siege of El Fasher has become emblematic of the war's cruelty—260,000 civilians, including 130,000 children, trapped in what satellite imagery reveals as a massive "kill-box" created by RSF sand berms.

The sexual violence is weaponized and widespread. Gang rape, forced marriage, and sexual slavery by RSF fighters have become routine instruments of terror. In areas recaptured by the SAF, the cycle of revenge continues: public executions without trial of civilians accused of collaborating with the RSF, mass arrests with detainees' fates unknown.

In January 2025, the United States made a historic determination: members of the RSF and allied militias have committed genocide in Sudan. Yet even this designation feels inadequate to capture the scope of suffering when one considers why this genocide has remained so invisible to the world.

In a piercing examination on 'Mehdi Unfiltered', Mehdi Hassan confronts the question that haunts this crisis: why has the media largely ignored this genocide for two years? Speaking with Guardian columnist Nesrine Malik and Darfur Women Action Group leader Niemat Ahmadi, the discussion exposes uncomfortable truths about global indifference.

The statistics they highlight are staggering: beyond the 30 million needing humanitarian assistance, disease compounds the horror—99,700 suspected cholera cases and over 2,470 cholera-related deaths as of August. Yet these numbers rarely penetrate Western consciousness. As Malik and Ahmadi explain, Sudan's suffering exists in a blind spot created by racism, donor fatigue, and a media ecosystem that values some lives over others.

This media neglect has real consequences. The escalation in 2025 has been catastrophic. In the first six months of the year alone, 3,384 civilians died—equaling 80 percent of the 4,238 civilian deaths throughout all of 2024. Each statistic represents entire worlds destroyed: families torn apart, communities erased, futures stolen.

Sudan now hosts the world's largest displacement crisis. More than 14 million people have been uprooted, with 3.3 million fleeing as refugees to neighboring countries. The ripple effects destabilize an entire region—Chad's refugee camps overflow, South Sudan barely able to support its own population now shelters over a million Sudanese, while Egypt and Ethiopia strain under the influx.

![Houda Ali Mohammed, 32, a displaced Sudanese mother of four, prepares food at a camp in Tawila, North Darfur, Sudan, during the war between the paramilitary Rapid Support Forces and the Sudanese army [File: Mohamed Jamal/Reuters]](/images/sudanese-family.jpg)

The international community's response has been a masterclass in collective failure. The UN refugee agency has received only 27 percent, or $266 million, of the $1 billion it requested for its emergency response. As one UN official noted with bitter understatement, "funding has trickled in."

The UN Fact-Finding Mission has called for immediate action: an arms embargo, International Criminal Court prosecutions, and accountability mechanisms. Sudan has even taken the unprecedented step of filing a complaint to the International Court of Justice, accusing the UAE of complicity in genocide due to its arms support for the RSF. Yet these legal maneuvers feel like rearranging deck chairs while Sudan burns.

Into this void, the Sudanese diaspora has stepped with remarkable resilience. From Baltimore to Melbourne, Sudanese communities organize basketball tournaments, crowdfund medical supplies, and send remittances that have become lifelines. As one organizer noted, Sudanese groups "have been doing the work of global organizations"—a damning indictment of institutional paralysis.

The arms continue to flow, the UN Security Council remains gridlocked, and regional powers pursue their proxy interests while Sudan bleeds. "The international community has the tools to act," the UN mission stated, warning that failure "would betray the very foundations of international law".

The UN's warning that Sudan's "darkest chapters may lie ahead" should haunt every conscience. As the war enters its third year with "no sign of resolution", we witness not just the failure of two armies but the collapse of the entire international protection system established after World War II.

For the Caribbean and the Global South, Sudan's tragedy carries particular resonance. This is what happens when former colonies are abandoned by the international order—when their suffering doesn't trend on social media, when their refugees don't look like those from Ukraine, when their resources matter more than their people. Today it's Khartoum and Darfur; tomorrow it could be anywhere that poverty, climate change, and political instability intersect.

The question Hassan, Malik, and Ahmadi force us to confront isn't just why we ignore Sudan, but what our silence says about who we value. The Sudanese people demand what every human deserves: protection, peace, and justice. Their voices, rising from refugee camps and diaspora communities, from detention "slaughterhouses" and besieged cities, ask a simple question that indicts us all: How many more must die before the world acts? The answer, written in blood across Sudan's killing fields, is already far too many.

-30-