BARBADOS | The Bajan Mirror: What Antigua Must See Before It’s Too Late

Mottley’s third consecutive 30-0 sweep carries stark warnings for Antigua and Barbuda’s opposition as elections loom

WiredJa Analysis | February 13, 2026

The numbers from Barbados arrived with the blunt finality of a coroner’s report. Thirty seats contested. Thirty seats won by the Barbados Labour Party. Zero for everyone else — for the third consecutive general election. When a democracy produces the same result three times running, the question is no longer whether the governing party is strong, but whether the opposition still has a pulse.

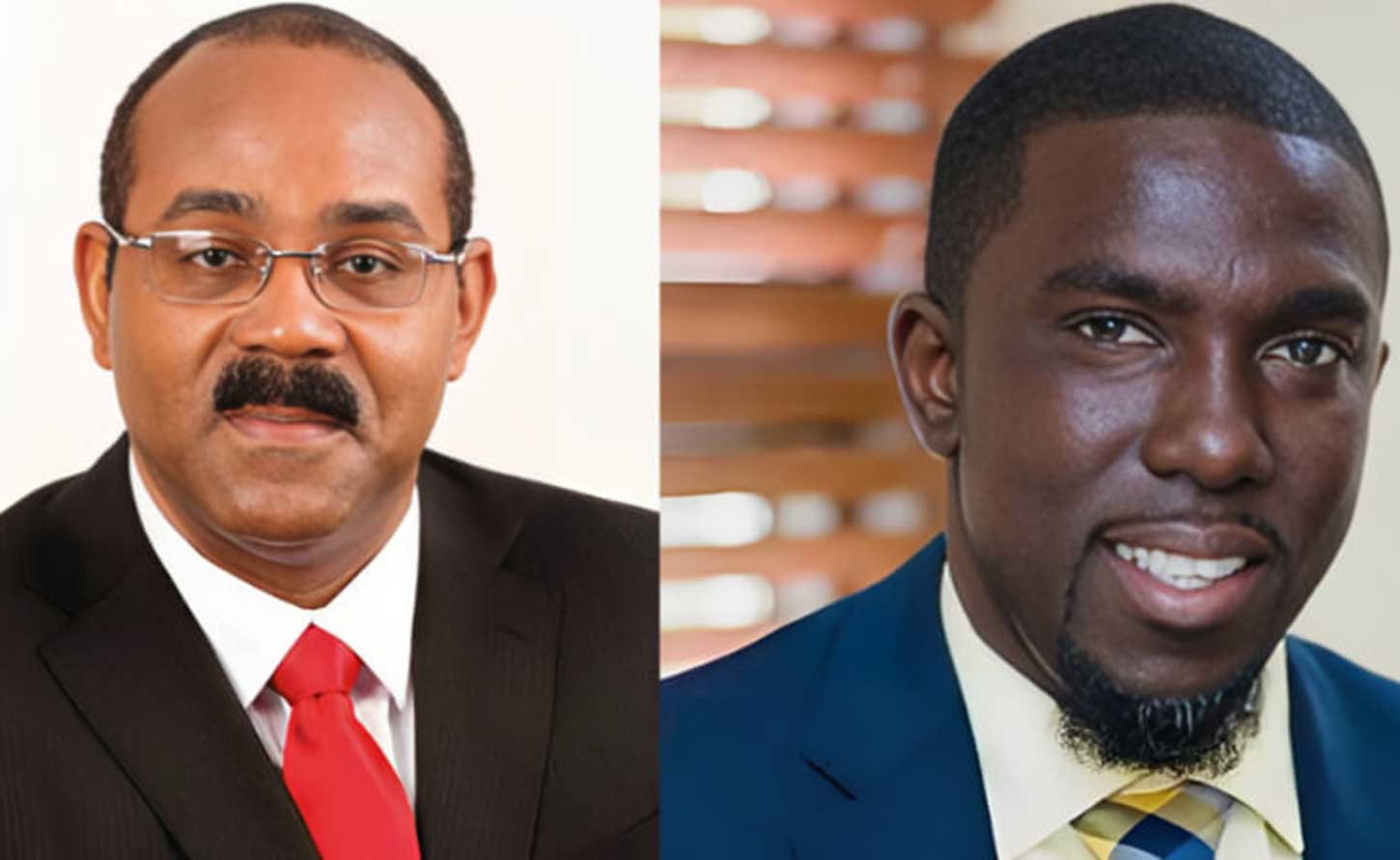

For Antigua and Barbuda, watching from across the Leeward Islands, Barbados on February 11 did not merely hold an election — it held up a mirror. And what that mirror reflects should alarm anyone invested in the health of Caribbean democracy, most urgently the United Progressive Party and the broader opposition apparatus in Antigua, where elections are constitutionally due by 2028 and Prime Minister Gaston Browne is already hinting they may come sooner.

The parallels are neither superficial nor coincidental. They are structural — rooted in the same democratic deficiencies, institutional asymmetries, and opposition failures that are becoming dangerously entrenched across the region.

The Anatomy of a Wipeout

But the devastation of the DLP is only half the story. Voter turnout plummeted to approximately 40–45%, down from 60% in 2018 and an already-concerning sub-50% figure in 2022. In a nation of roughly 271,000 registered voters, the majority chose not to participate at all. The BLP did not win a mandate from the people of Barbados — it won a mandate from the fraction of Barbadians who still believe the exercise matters.

This trajectory is not a statistical curiosity. It is the signature of democratic decay — a feedback loop where opposition collapse breeds voter apathy, which in turn reinforces government dominance, which further discourages opposition viability. Antigua is not yet at the terminal stage of this cycle, but it is closer than many appreciate.

Opposition Fragmentation: The Caribbean Disease

The DLP’s failure was not simply a matter of facing a popular incumbent. It was compounded by a fragmented opposition landscape. Ten political parties fielded candidates in Barbados’s 30 constituencies, including an independent coalition of smaller parties — the New National Party, the United Progressive Party (Barbados), and the Conservative Barbados Leadership Party. These micro-parties collectively siphoned votes without winning seats, a pattern DLP General Secretary Pedro Shepherd acknowledged when he pointed to the damage caused by third-party fragmentation.

In Antigua, this dynamic already exists. The Democratic National Alliance, while largely diminished, has historically split the anti-ABLP vote. More damaging still has been the UPP’s internal fragmentation. The defection of MP Anthony Smith in mid-2024 — crossing from the opposition to effectively bolster the ruling party — echoes Thorne’s own floor-crossing journey in reverse: Thorne moved from BLP backbencher to DLP leader, a transition that never fully resolved questions of legitimacy and party loyalty. Smith’s departure from the UPP similarly wounded opposition credibility precisely when unity was most needed.

“We have to probably go back to the drawing board to see why all of our efforts are still not translating into votes.”

— Pedro Shepherd, DLP General Secretary, February 12, 2026

The lesson is unambiguous: in small Caribbean democracies operating under first-past-the-post systems, opposition fragmentation is not a philosophical luxury — it is a death sentence. Every splinter party, every internal rupture, every ego-driven defection transfers power directly to the incumbent.

The Campaign Finance Chasm

This asymmetry is not accidental. Governing parties in the Caribbean enjoy de facto fundraising advantages through their control of state contracts, appointments, and regulatory favour. Without campaign finance laws mandating disclosure, spending limits, or public funding mechanisms, the opposition enters every election cycle fighting with one hand tied. The DLP’s late manifesto launch — dropping their platform just days before the February 11 vote — was widely read not as strategic positioning but as evidence of organizational and financial incapacity.

Antigua suffers from identical deficiencies. The ABLP, having held power since 2014, commands the full machinery of incumbency — patronage networks, media access, and the ability to time elections for maximum advantage. The UPP, meanwhile, has struggled to attract consistent financial backing, a reality compounded by the business community’s pragmatic tendency to align with whoever controls the state apparatus. Without legislative reform on campaign financing, the structural playing field will remain permanently tilted.

Voter Apathy: The Silent Kingmaker

Barbados’s collapsing turnout deserves particularly close examination from Antigua. The conventional assumption is that low voter turnout reflects disillusionment with both parties equally. The electoral data suggests otherwise. Low turnout in the Caribbean context disproportionately harms the opposition, because governing parties maintain floor support through patronage, direct constituency intervention, and the simple psychological advantage of appearing inevitable. Disenchanted voters who stay home are overwhelmingly people who might have voted for change — but concluded that change was impossible.

Barbados’s experience reveals an additional dimension: the absence of democratic guardrails accelerates apathy. Researchers accompanying the 2026 election expressed shock at Barbados’s lack of a Freedom of Information Act, the absence of integrity legislation, and the non-existence of campaign financing laws. These are not bureaucratic niceties. They are the infrastructure of accountability — and without them, citizens have no institutional mechanism to hold power to account between elections, which in turn makes elections themselves feel performative rather than consequential.

Antigua faces a similar accountability vacuum. The UPP’s most potent campaign argument may not be any single policy proposal, but a governance reform agenda that gives citizens reasons to believe their vote connects to actual accountability mechanisms. Barbados demonstrates what happens when that connection erodes entirely: people simply stop showing up.

The Dominant Leader Paradox

Mia Mottley’s international profile — as a leading voice on climate-vulnerable nation debt reform, a regular at the UN General Assembly podium, and arguably the Caribbean’s most globally recognized leader — created an aura of inevitability that the DLP never pierced. Her framing of the election as a choice between her global-facing approach and the opposition’s narrower domestic focus effectively positioned any vote against her as parochial and backward-looking.

Gaston Browne operates a similar playbook in Antigua, cultivating a profile as a decisive regional figure — the Alpha Nero yacht seizure, infrastructure projects, UWI engagement — that positions him above ordinary political contestation. Browne has already begun signaling that elections could come early, telling ABLP supporters that the call is “coming soon.” This is a direct advantage borrowed from Mottley’s handbook: calling elections at the moment of maximum opposition disarray.

The UPP’s challenge is to develop a counter-narrative that acknowledges Browne’s strengths while relentlessly connecting to bread-and-butter concerns — water supply failures, infrastructure deficits, the cost of living, economic inequality — where incumbents are vulnerable regardless of their international stature. The DLP attempted this, campaigning on domestic issues, but lacked the organizational coherence and messaging discipline to make it stick. Antigua’s opposition must study this failure closely.

The Leadership Question

Thorne’s decision to step down immediately after the Barbados results carries its own instructive weight. His leadership was contested from the beginning — a floor-crosser who assumed the helm of a party he had only recently joined, facing persistent questions about legitimacy from party stalwarts. The internal dissent that plagued his tenure was never fully resolved, and it showed on election day.

In Antigua, UPP leader Jamale Pringle faces a structurally similar challenge. High-profile resignations — Dr. Edmond Mansoor, Sean Bird, former PRO Damani Tabor — and the defection of Anthony Smith have created a narrative of organizational instability. Pringle has responded with defiance, declaring he is “still standing,” but defiance alone did not save Thorne. The UPP must resolve its leadership questions decisively and publicly, demonstrating unity not through rhetoric but through a visible, functioning campaign apparatus with announced candidates in every constituency.

Barbados teaches that opposition parties in the Caribbean cannot afford protracted leadership disputes heading into elections. The window between “resolving internal issues” and “facing voters” is razor-thin in small island democracies where the prime minister controls the election calendar.

The Democratic Stakes

It is worth noting that Mottley herself expressed concern about the DLP’s total absence from Parliament. She has previously made efforts to ensure the opposition had some Senate representation, recognizing that a legislature without dissent is not a legislature at all. Former Grenada Prime Minister Keith Mitchell — the only other Caribbean leader to achieve three consecutive clean sweeps — recently retired from politics, leaving behind a country that had to rebuild opposition capacity essentially from scratch.

This is the endgame that Antigua must avoid. The 2023 election — where the ABLP barely held on with 9 of 17 seats — demonstrated that competitive democracy in Antigua is not dead. But the margin between competitive democracy and Barbados-style one-party dominance is thinner than it appears, particularly when the opposition is hemorrhaging members, struggling with funding, and facing an incumbent who controls the timing of the next contest.

The Barbados mirror does not show Antigua its future as a certainty. It shows Antigua its future as a probability — unless deliberate, structural corrections are made. Those corrections include opposition unity as a non-negotiable discipline, a governance reform platform that gives voters institutional reasons to engage, innovative approaches to campaign funding that reduce dependence on patronage-adjacent capital, and a leadership structure that projects stability rather than siege mentality.

The clock did not start ticking on February 11 when Barbados went to the polls. It has been ticking for some time. But the alarm just got considerably louder.

WiredJa Analysis — Caribbean-Centered Journalism

-30-