CARICOM | Four Countries, One Question: Where Is Haiti in CARICOM's Free Movement Dream?

As the Caribbean Community’s integration takes a historic leap forward, the region's most vulnerable member remains conspicuously excluded

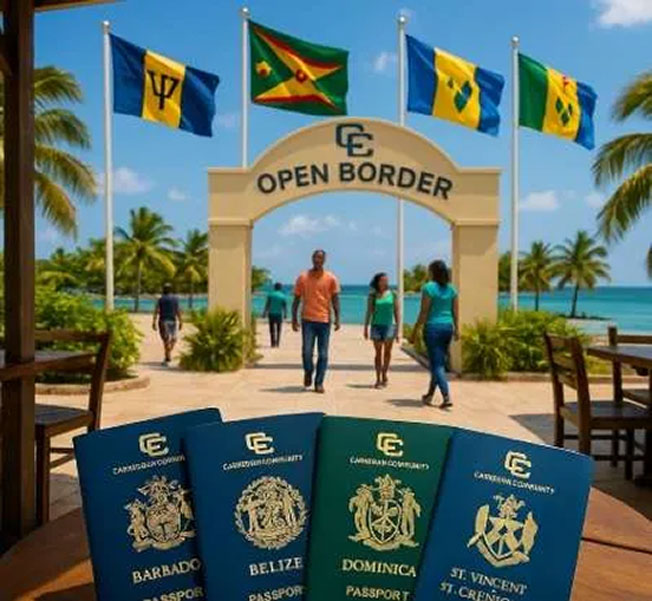

Today, October 1, 2025, the Caribbean or more definitively CARICOM, will witness something remarkable: after more than five decades of speeches, summits, and stalled promises, free movement of people will finally become reality for citizens of Barbados, Belize, Dominica, and St. Vincent and the Grenadines.

A Barbadian will be able to settle indefinitely in Belize. A Vincentian can work without restriction in Dominica. Their children will access public schools. Their families will receive healthcare. No six-month limits. No work permit bureaucracy. Just movement, as free as the waters that connect these islands.

This is genuine progress, and it deserves recognition. The four countries have done what the rest of CARICOM has only talked about, establishing registration systems, security protocols, and complaint mechanisms to make integration tangible rather than rhetorical.

They've invoked the Enhanced Cooperation Protocol, essentially telling their more hesitant neighbors: we're moving forward, with or without you.These include the following: Indefinite Stay at Entry: Nationals of the four participating Member States will receive a stamp or digital record of indefinite stay on arrival.

Indefinite Stay at Entry: Nationals of the four participating Member States will receive a stamp or digital record of indefinite stay on arrival.

Registration: Systems have been established to allow for registration of incoming nationals, enabling access to services such as education and healthcare, and allowing national agencies to plan for any increased demand.

Security and Health Safeguards: Effective oversight measures are in place to ensure that individuals who pose a threat to national security, public health, or would become a cost to the public are either denied entry or subject to removal.

These measures will be supported by the CARICOM Implementation Agency for Crime and Security (IMPACS) which coordinates Member States security cooperation and administers the Advanced Passenger Information System (APIS), which mandates submission of passenger data before travel.

Complaints Mechanism: Nationals who experience difficulties at ports of entry or after entry may use the CARICOM Complaints Procedure, which is already operational under the CSME.

Forms are available at all ports of entry, and complaints will be reviewed within two weeks, with investigations completed within eight weeks, where necessary.

The Member State We Prefer to Forget

But as we applaud this achievement, we must ask an uncomfortable question that threatens to expose the hollow core of Caribbean solidarity: What about Haiti?

Haiti has been a full member of CARICOM since 2002—twenty-three years of ostensible belonging to a community that proclaims unity as its founding virtue.

Yet as Jamaicans, Trinidadians, and Guyanese enjoy varying degrees of visa-free access across the region, Haitians face a starkly different reality.

They encounter visa requirements, bureaucratic hostility, and in some member states, outright discrimination.

They are deported from countries that simultaneously host their prime ministers at CARICOM summits. They are the exception to every rule of Caribbean kinship.

The four countries pioneering free movement tomorrow have prepared elaborate systems to welcome each other's citizens—indefinite stay stamps, registration protocols, access to social services.

One wonders: have they prepared similar systems for their Haitian brothers and sisters? Or does Haiti's full membership come with an unspoken asterisk that reads: terms and conditions apply?

The Silence of Solidarity

Here is what galls most: the silence. CARICOM meetings produce eloquent communiqués about regional integration, about the Caribbean family, about our shared destiny as small island developing states confronting global challenges together.

But when it comes to Haiti—currently engulfed in a humanitarian catastrophe, with gangs controlling Port-au-Prince and thousands displaced—where are the voices demanding that integration include Port-au-Prince as readily as it includes Bridgetown or Belmopan?

Who speaks for Haiti in these rooms where free movement is negotiated? Which prime minister or foreign minister stands up and says: we cannot build a community that excludes our most vulnerable member? The answer appears to be no one, or at least no one loudly enough to matter.

The Dominican Paradox

And then there's the absurdity that should shame the entire region: the Dominican Republic has been actively seeking CARICOM membership, knocking persistently on the door of a community that Haiti already belongs to. Let that sink in.

A country that shares the island of Hispaniola with Haiti, that deports Haitians in droves, that has constructed an entire national identity partly on anti-Haitian sentiment, that denies citizenship to people of Haitian descent born on Dominican soil—this country wants to join the Caribbean family.

The Dominican Republic's treatment of Haitians is well-documented and brutal: mass deportations, denial of basic rights, a wall being constructed along the border, and a systematic campaign to render Haitians stateless.

Yet CARICOM entertains their membership bid while doing precious little to ensure that Haiti, an existing member, receives even basic dignity within the regional framework.

What message does this send? That CARICOM values potential economic benefits from Santo Domingo more than the human rights of Port-au-Prince? That a country can brutalize your existing member and still be welcomed to the table? The contradiction is staggering: Haiti belongs to CARICOM in name, but can the same be said in practice when its island neighbor—an active oppressor—is courted for membership while Haitians remain second-class citizens within their own regional community?

Haitians at the Dominican Republic Border awaiting deportation. In the Dominican Republic, some degree of anti-Haitian xenophobia has been a basic part of national politics.The Comfortable Excuses

Haitians at the Dominican Republic Border awaiting deportation. In the Dominican Republic, some degree of anti-Haitian xenophobia has been a basic part of national politics.The Comfortable Excuses

The justifications are predictable and cowardly. Haiti is "different"—French-speaking in an Anglophone community, though Belize speaks English, Spanish, and Creole without exclusion.

Haiti is "unstable"—as if Jamaica's garrison communities or Trinidad's gang violence represent models of security. Haiti is "too poor"—ignoring that several CARICOM members struggle with similar poverty metrics, yet face no comparable ostracism.

Strip away the diplomatic language, and what remains is more troubling: anti-Blackness within Blackness, class prejudice masquerading as practical concerns, and a regionalism that extends only to those deemed sufficiently "Caribbean" by unstated but rigidly enforced criteria.

Integration for Whom?

The cruel irony is that CARICOM's rhetoric demands solidarity when convenient. When hurricanes strike, we rally. When international forums require a unified Caribbean voice, Haiti's vote counts.

When the region needs to project strength through numbers, Port-au-Prince's membership is touted. But when integration requires actual commitment—when it means Haitian nurses could work in Barbados, Haitian teachers in Dominica, Haitian families settling in St. Vincent—suddenly the community discovers insurmountable obstacles.

This selectivity corrodes the moral foundation of regional integration. If CARICOM means anything beyond economic convenience and diplomatic coordination, it must mean that Caribbean people can build lives throughout the Caribbean. All Caribbean people. Not just those from countries whose passports confer privilege.

The Reckoning We Avoid

Tomorrow's milestone is real. The four countries implementing free movement deserve credit for political courage and administrative competence. They are proving that regional integration need not remain forever aspirational. But they are also highlighting, perhaps inadvertently, the limits of Caribbean solidarity.

As citizens of Barbados, Belize, Dominica, and St. Vincent and the Grenadines celebrate their new freedoms, as they book flights knowing they can stay indefinitely in each other's countries, one question should haunt the achievement: Why are we celebrating integration that excludes 11 million Caribbean people simply because they live in Port-au-Prince rather than Kingstown?

The answer matters because it will define what CARICOM actually is. Is it a community of convenience, extending rights to those who least need them while excluding those most desperate for regional solidarity? Or is it capable of the difficult, uncomfortable work of inclusion?

October 1, 2025, marks progress. But until a Haitian can move as freely through the Caribbean as a Barbadian, that progress remains incomplete, undermined by the very exclusion it perpetuates. Someone needs to speak for Haiti in these negotiations. The question is whether anyone will.

-30-