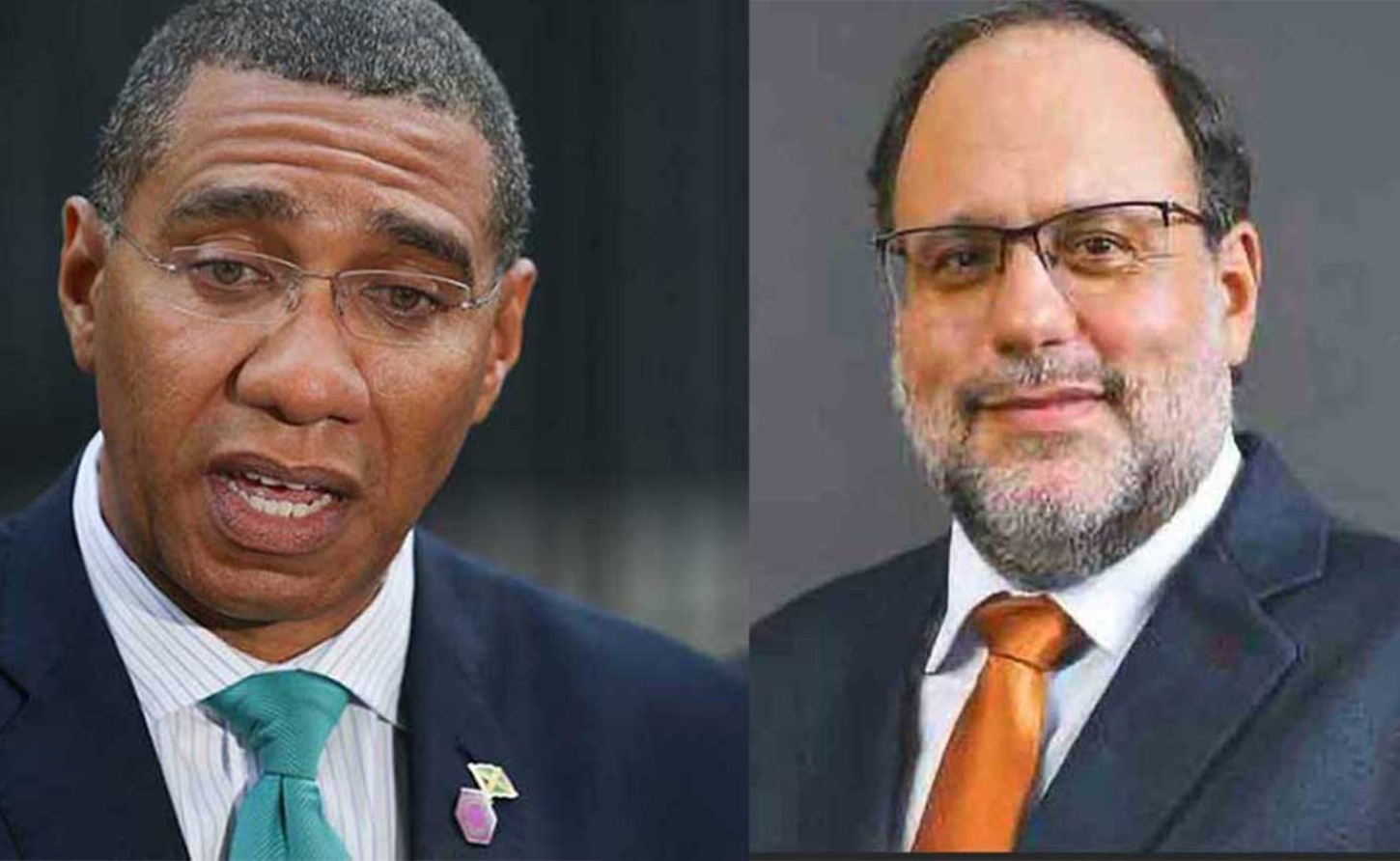

DIASPORA | Are You Jamaican Enough? PM Holness' Citizenship Test Alarms Overseas Community

MONTEGO BAY, Jamaica, August 29, 2025 - The theatrical flourish was unmistakable. In the heat of Jamaica's final leadership debate before Wednesday's general election, Opposition Leader Mark Golding's birth certificate was dramatically presented, certifying his July 19, 1965 birth at the University of the West Indies Hospital in Kingston, to a British father, Sir John Golding.

Prime Minister Andrew Holness' response was swift and apparently intending to be philosophical: "It is not your birth that makes you a Jamaican, it is the choices you make."

Yet if we follow Holness's logic to its natural conclusion, his statement raises profound questions that extend far beyond the political theater of campaign season.

What of the estimated 1.5 million Jamaicans living in the diaspora who, by circumstance rather than preference, have made the "choice" to pursue livelihoods abroad? Does their decision to seek opportunities in Toronto, London, New York, or Miami somehow invalidate their Jamaican identity?

The Prime Minister's assertion, while politically expedient, opens a constitutional Pandora's box that threatens to redefine citizenship itself. Under Jamaica's Constitution, citizenship is established through birth, descent, registration, or naturalization—not through a subjective assessment of one's "choices."

To suggest otherwise ventures into dangerous territory where citizenship becomes conditional upon meeting undefined criteria of national loyalty or life decisions.

Golding's story embodies the complexity of modern Caribbean identity. Born to a British father who dedicated his life to Jamaica as an orthopedic surgeon serving the island's most vulnerable populations, Golding inherited British citizenship by descent—a legal reality shared by thousands of Jamaicans with similar family histories.

Rather than leveraging this privilege for permanent exodus, Golding made the conscious decision to return, establishing his home, building his business, and eventually offering himself for public service.

His father's legacy speaks volumes about the choice-versus-birth debate. Sir John Golding could have practiced medicine anywhere in the Commonwealth, yet chose to dedicate decades to Jamaica's public health system.

Now his son follows a similar path, transitioning from private sector success to political leadership—embodying the very "choices" Holness claims define true Jamaican identity.

The irony runs deeper when considering Jamaica's economic dependence on diaspora contributions and the island's deep migratory traditions. Since the Panama Canal construction era of 1881-1889, Jamaicans have been migratory workers, traveling to Cuba, Belize, and the United States as farm workers and casual laborers to make a living.

This pattern continued through the 20th century with the British West Indian program that brought Jamaican workers to American farms during World War II, and has evolved into today's skilled migration where Jamaican nurses, teachers, doctors, and technology professionals are actively recruited by overseas entities seeking their expertise.

Yet these citizens, spanning generations of economic migration from manual labor to professional excellence, would under Holness's logic be classified as having made "un-Jamaican choices," even as their remittances exceed $3 billion annually—roughly 15% of the country's GDP.

Their economic choices abroad directly support Jamaica's survival and development, continuing a tradition of labour migration that predates Jamaica's independence by nearly a century and now encompasses the very professionals the island desperately needs but struggles to retain due to economic constraints.

The timing of Holness's rhetoric is particularly troubling given current immigration realities. At a moment when Jamaicans in the United States are understandably nervous about being unceremoniously detained by immigration enforcement and potentially deported, the suggestion that their "choices" might disqualify them from Jamaican citizenship creates a dangerous vulnerability.

If diaspora Jamaicans cannot count on their home government to recognize their citizenship rights because of decisions made for economic survival, they face the terrifying prospect of statelessness—unwanted by their adopted countries and potentially rejected by their birthplace.

Holness's rhetoric also ignores the reality that dual citizenship has become increasingly common across the Caribbean. Trinidad and Tobago, Barbados, and other regional neighbors have embraced dual nationals in leadership positions without constitutional crisis.

The region's history of migration—forced and voluntary—means that citizenship by descent is often the rule rather than the exception.

The constitutional implications are troubling. If citizenship depends on choices rather than legal status, who determines which choices qualify as sufficiently Jamaican? Is working abroad disqualifying? What about studying overseas? Investing in foreign markets?

The subjective nature of such assessments opens the door to arbitrary disenfranchisement based on political convenience rather than legal principle.

As Jamaicans prepare to vote on Wednesday, they face a choice that extends beyond party politics. They must decide whether citizenship remains a constitutional guarantee or becomes subject to the subjective judgments of political leaders.

Golding's birth certificate may have provided campaign theatre, but the real drama lies in whether Jamaica will embrace its complex, interconnected identity—rooted in more than a century of necessary migration—or retreat into narrow definitions of belonging that could abandon the very people who sustain the island's future when they need protection most.

-30-