GRENADA | ACTIF2025: Caribbean and Africa Forge $300M Path to Economic Independence

Grenada summit charts course for transformative trade alliance as regions seek alternatives to traditional Western partnerships.

ST. GEORGE'S GRENADA, July 30, 2025 - The scent of nutmeg hung heavy in the St. George's air as more than 2,100 delegates from across the Global South gathered for what may prove to be a watershed moment in South-South cooperation.

Under the banner "Resilience and Transformation," the forum wasn't merely about rekindling ancestral ties between Africa and the Caribbean. It was about money, markets, and the kind of strategic thinking that emerges when small island states and developing nations realize they possess collective bargaining power that individual dependency relationships cannot match.

The Numbers Tell the Story

The $300 million in announced deals spanning infrastructure, manufacturing, logistics, digital services, tourism, and agribusiness represents more than impressive figures—it signals a fundamental shift in how Caribbean nations are approaching economic development.

Rather than relying exclusively on traditional partners in North America and Europe, these agreements demonstrate a calculated pivot toward partnerships that offer genuine reciprocity.

The endorsement of an Africa-Caribbean Free Trade Arrangement stands as perhaps the forum's most significant outcome. Unlike the often-criticized Economic Partnership Agreements that Caribbean nations signed with Europe, this proposed arrangement promises to "eliminate trade barriers, enhance regulatory coherence, and unlock mutual market access" between regions that share similar development challenges and complementary resource bases.

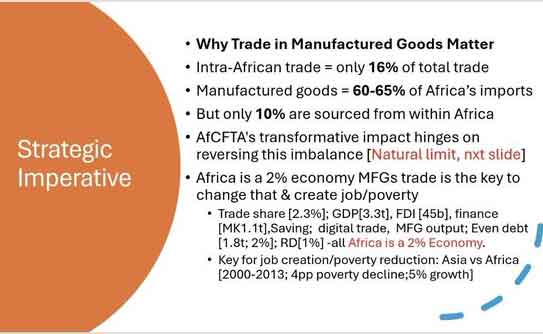

To understand the transformative potential, consider current trade patterns. Caribbean imports from Africa remain negligible—less than 2% of total trade for most CARICOM nations. Similarly, African exports to the Caribbean represent a fraction of the continent's external trade.

This isn't due to lack of complementarity; it's the result of colonial-era trade architecture that continues channeling Caribbean commerce through metropolitan centers in London, Miami, and Montreal.

A Trade and Business Development Cooperation Agreement was formally signed by the Trinidad and Tobago, and Grenada Chambers of Industry and Commerce in an effort to deepen regional cooperation and strengthen economic resilience.Beyond Trade: Strategic Autonomy

A Trade and Business Development Cooperation Agreement was formally signed by the Trinidad and Tobago, and Grenada Chambers of Industry and Commerce in an effort to deepen regional cooperation and strengthen economic resilience.Beyond Trade: Strategic Autonomy

The communiqué's emphasis on establishing "direct air and maritime links" between Africa and the Caribbean reveals sophisticated strategic thinking. Currently, a Jamaican businesswoman seeking to export Blue Mountain coffee to Lagos must route through Miami or London—a colonial-era transportation architecture that artificially inflates costs and maintains dependency on Western logistics networks.

The forum's call for eliminating visa restrictions between the regions similarly recognizes that economic integration requires human mobility. When Grenadian Prime Minister Dickon Mitchell and his OECS counterparts endorsed the Global Africa Commission, they weren't engaging in Pan-African romanticism—they were acknowledging that demographic realities favor South-South partnerships.

Africa's youthful population and the Caribbean's educational infrastructure create natural synergies that transcend nostalgic appeals to shared heritage.

Consider the skills equation: Caribbean nations possess well-developed tertiary education systems but limited domestic markets for graduates. Meanwhile, Africa's rapidly expanding economies face critical skills shortages in precisely the areas where Caribbean institutions excel—financial services, hospitality management, maritime studies, and renewable energy engineering.

The forum's emphasis on addressing "digital skills shortages and capacity gaps in telecommunications" through "skills and knowledge transfer programmes" reflects this complementarity.

The Honourable Dickon Amiss Thomas Mitchell, Prime Minister of GrenadaClimate Justice as Economic Strategy

The Honourable Dickon Amiss Thomas Mitchell, Prime Minister of GrenadaClimate Justice as Economic Strategy

The joint call for climate action represents perhaps the most analytically sophisticated element of the ACTIF agenda. Both regions face existential threats from climate change—rising sea levels for Caribbean islands, desertification and extreme weather for African nations. Their united advocacy for climate justice isn't merely moral positioning; it's economic necessity.

Small island developing states (SIDS) and African nations possess minimal responsibility for global carbon emissions yet bear disproportionate consequences. By speaking "with one voice on global matters," as the communiqué phrases it, these nations are leveraging collective influence to demand the kind of climate financing and technology transfer that individual advocacy cannot secure.

The economic dimensions are stark. The Caribbean requires an estimated $22 billion annually for climate adaptation, while Africa needs over $300 billion. Traditional donor mechanisms provide inadequate financing on terms that often exacerbate debt vulnerabilities.

An Africa-Caribbean alliance could pioneer innovative climate financing mechanisms, potentially including debt-for-climate swaps, blue bonds, and carbon credit arrangements that benefit both regions while addressing global environmental challenges.

The Afreximbank Factor

The African Export-Import Bank's central role in orchestrating ACTIF2025 deserves particular attention. Under President Benedict Oramah's leadership, Afreximbank has evolved beyond traditional development finance, positioning itself as an architect of South-South economic integration.

The African Export-Import Bank's central role in orchestrating ACTIF2025 deserves particular attention. Under President Benedict Oramah's leadership, Afreximbank has evolved beyond traditional development finance, positioning itself as an architect of South-South economic integration.

The bank's Partnership Agreement, now signed by 13 countries with others expected to follow, provides the institutional framework that previous Pan-African initiatives often lacked.

This isn't merely about providing capital—it's about creating alternative financial architecture. When Caribbean nations can access project financing through Afreximbank rather than relying exclusively on World Bank or IMF conditionalities, they gain policy space that traditional development partnerships often constrain.

The bank's $5 billion commitment to Caribbean infrastructure development, announced at previous ACTIF forums, is already materializing in renewable energy projects across the region.

The institution's approach differs markedly from traditional development finance. Rather than imposing standardized structural adjustment programs, Afreximbank tailors its "financing, facilitation and advisory services" to local contexts while maintaining commercial viability.

This model has particular appeal for Caribbean governments seeking to balance fiscal discipline with social development priorities.

Cultural Economy as Soft Power

The forum's recognition of the "creative and digital economy—including music, film, literature, fashion, visual arts, and sports" as growth engines reflects nuanced understanding of contemporary economics.

Caribbean musical genres and African creative industries possess global influence that translates into measurable economic value. The proposed Global Africa Athletics Championships isn't sports diplomacy for its own sake—it's about building brand recognition that enhances trade relationships.

Consider the economic impact of cultural exports: Jamaica's music industry generates over $100 million annually, while Nigeria's Nollywood film industry approaches $1 billion in value. South Africa's fashion industry increasingly influences global trends, and Caribbean carnival traditions drive tourism revenues across the region.

The ACTIF emphasis on creative industries recognizes that cultural products can serve as economic multipliers, creating demand for related goods and services while building positive associations with regional brands.

Institutional Architecture and Challenges

The forum's success in attracting representatives from the African Union Commission, CARICOM Secretariat, African Continental Free Trade Area Secretariat, and Organisation of Eastern Caribbean States demonstrates serious institutional commitment. However, translating political momentum into operational reality requires addressing persistent structural challenges.

Transportation remains the most immediate obstacle. Currently, no direct commercial flights connect major Caribbean hubs with African cities, forcing travelers through expensive European or North American connections.

Maritime shipping faces similar constraints, with most Africa-Caribbean cargo requiring trans-shipment through third-country ports. The forum's call for "sustainable and commercially viable trade corridors" acknowledges that political agreements without logistical infrastructure remain largely symbolic.

Regulatory alignment presents equally complex challenges. While both regions share similar legal traditions—predominantly English common law systems—divergent regulatory frameworks complicate cross-border business operations. The proposed free trade arrangement will require extensive harmonization of standards, customs procedures, and business regulations.

Looking Ahead: September's Test

The September 2025 African-Caribbean Summit in Addis Ababa will determine whether ACTIF2025's ambitious agenda translates into institutional reality. The presence of 11 heads of state and government in Grenada, including former presidents Olusegun Obasanjo and Mahamadou Issoufou, suggests serious political commitment.

Yet challenges remain formidable. Infrastructure deficits, limited manufacturing capacity, and regulatory misalignment continue constraining intraregional trade. The test will be whether the political momentum generated in St. George's can overcome the structural obstacles that have historically limited South-South cooperation.

The stakes extend beyond regional economics. Success could demonstrate that middle-income developing nations can create viable alternatives to traditional North-South dependency relationships. Failure might reinforce skepticism about South-South cooperation's practical limitations.

As delegates departed Grenada's Maurice Bishop International Airport, they carried more than business cards and memoranda of understanding. They carried the possibility that two regions long relegated to the periphery of global economics might finally be charting their own course toward the center.

Whether that possibility becomes reality will depend on converting the political capital generated in St. George's into the practical infrastructure, institutional frameworks, and business relationships that sustainable economic integration requires.

The next twelve months will reveal whether ACTIF2025 marks the beginning of genuine transformation or merely another chapter in the long history of unfulfilled South-South aspirations.

The author acknowledges that this analysis is based on the official ACTIF2025 communiqué and publicly available information.

-30-