JAMAICAN Democracy on Trial: Buchanan Takes Election Fight to Supreme Court

Land economist challenges electoral watchdog's refusal to investigate alleged voting irregularities in Prime Minister's constituency

KINGSTON, Jamaica, October 9, 2025 - Two weeks after Jamaica's electoral watchdog rejected his complaints of voting irregularities, Paul Buchanan walked into the Supreme Court Wednesday morning with a different strategy: if the Constituted Authority won't refer his case to the Election Court, he'll force them to.

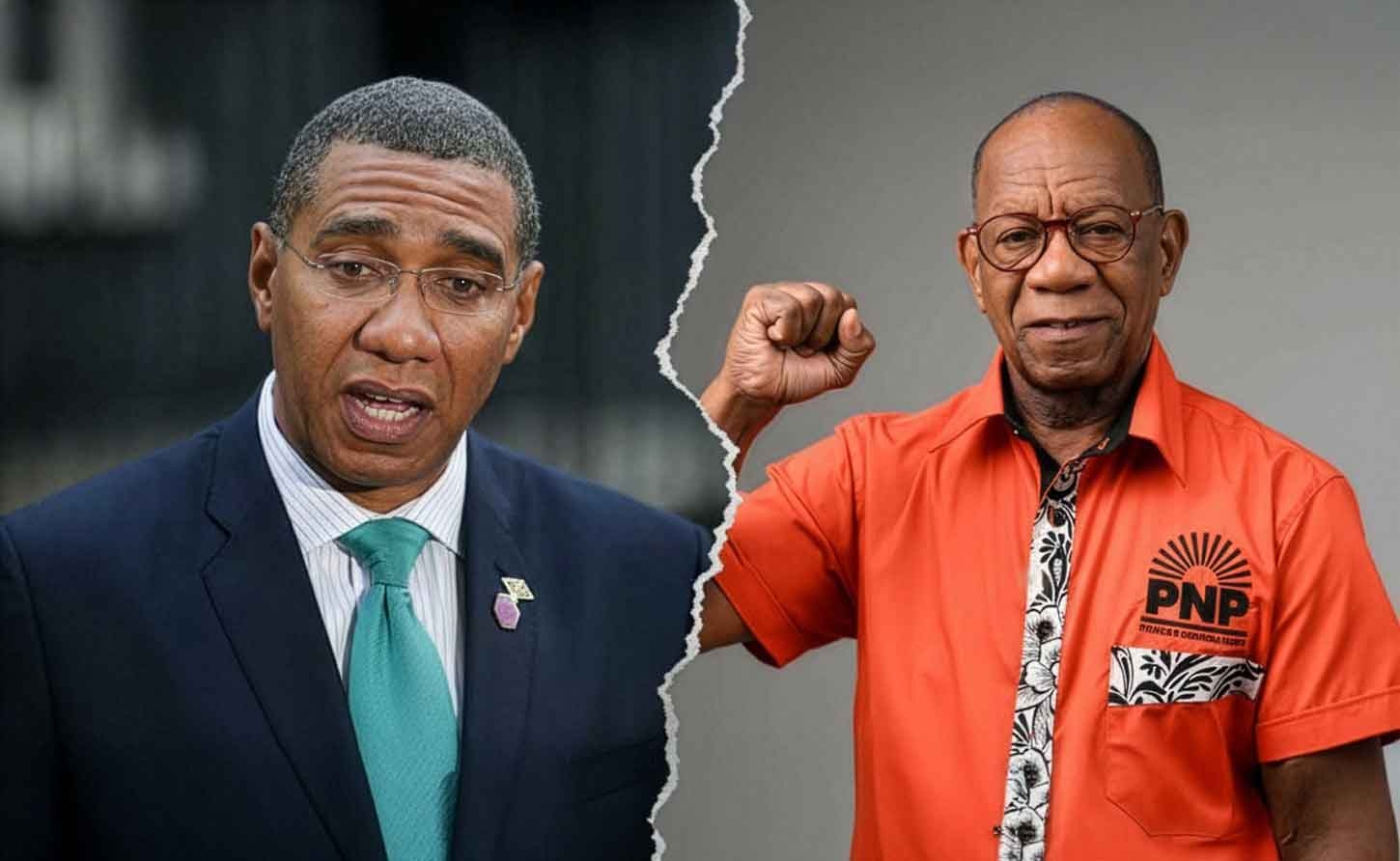

The People's National Party candidate, who lost his bid to unseat Prime Minister Dr. Andrew Holness in the St. Andrew West Central constituency on September 3, has filed for judicial review of the Constituted Authority's decision, arguing that the body designed to screen election complaints has overstepped its mandate by acting as judge and jury rather than gatekeeper.

At the heart of Buchanan's legal challenge lies a fundamental question about Jamaica's electoral oversight: When evidence of alleged voting irregularities is presented, who decides if it's credible enough to investigate—a screening body or the courts established specifically to adjudicate such matters?

The Numbers and the Narrative

The election results weren't particularly close. Holness secured 7,054 votes to Buchanan's 4,953—a margin of more than 2,000 votes in a constituency where Holness as the Prime Minister has held sway for years. But Buchanan, a land economist and experienced electoral campaigner familiar with the intricacies of Jamaica's voting process, insists the numbers tell only part of the story.

What happened on election day in the volatile communities of Olympic Gardens and Molynes Gardens, he argues, wasn't democracy in action but democracy under duress.

Within days of the September 3 vote, Buchanan's team began gathering affidavits—sworn statements from poll watchers, party workers, and election officials detailing a cascade of irregularities that, they claim, fundamentally compromised the electoral process in key divisions where Buchanan held support.

On September 16, his attorney Hugh Wildman delivered the package to the Constituted Authority, the body established under Section 44A of the Representation of the People Act to receive and evaluate complaints about electoral conduct. The Authority had 14 days to review the evidence and decide whether to refer the matter to the Election Court.

On September 30, the answer came back: No.

Five Affidavits, One Rejected Complaint

The evidence Buchanan presented painted a disturbing picture of election day in St. Andrew West Central. Five witnesses provided sworn testimony detailing alleged irregularities that touched on nearly every aspect of electoral integrity—from how votes were cast to how they were counted to how ballot boxes were transported.

Marsha Powell's affidavit identified what she described as multiple instances of double voting—voters casting ballots more than once, a fundamental violation of electoral law. The Constituted Authority, Buchanan's legal filing argues, misunderstood Powell's testimony, interpreting her statement as referring to a single incident rather than several discrete acts of electoral fraud.

Everton Sands's testimony raised perhaps the most alarming allegation: ballot box tampering through route manipulation. According to Sands, ballot boxes from Jews Avenue Primary School in the Molynes division—described as a Buchanan stronghold—were diverted around 8 p.m. from their agreed route to the volatile Olympic Way Corridor. The deviation, unknown to Buchanan's campaign at the time, allegedly compromised the integrity of those ballots in breach of Section 37(b) of the Election Petitions Act.

The question wasn't just where the boxes went, but why the agreed-upon route was changed and who authorized the change.

Warren Blake's affidavit detailed a different kind of pressure: voter intimidation through overwhelming presence. He described overcrowding at polling stations by Holness supporters, music blaring within prohibited areas around polling clusters, and activities designed to create an atmosphere of intimidation that would discourage opposition voters from casting ballots.

Iteisha Johnson's testimony added a darker dimension. She described men wearing ski masks inside the polling station—a sight sufficiently threatening that she felt compelled to abandon her post, leaving the station without any representative from Buchanan's campaign to monitor the voting process.

Avia Myles's affidavit corroborated the intimidation narrative, providing additional evidence of what Buchanan's legal team argues were systematic attempts to suppress voter turnout in areas favorable to their candidate.

The Legal Crossroads

The Constituted Authority reviewed these affidavits and concluded they didn't meet the evidentiary standard. In its September 30 ruling, the Authority stated: "Having analyzed the affidavits, the Constituted Authority finds that the alleged irregularities do not satisfy the standard contemplated by the wording of section 37(e) of the Election Petitions Act or as enunciated by the Election Court in Blake v Holness."

The Authority's conclusion: "In the circumstances, the Constituted Authority refuses Mr. Buchanan's request for it to file an application to the Election Court to void the election in the constituency of Saint Andrew, West Central."

But that's precisely where Buchanan and his legal team believe the Authority went wrong.

"We are saying that the Constituted Authority usurped the function of the election court," Wildman told Radio Jamaica News Wednesday afternoon. "It is not their job to do that. Their job is to determine whether or not there is credible evidence to go to the election court. And once there is credible evidence to go to the election court, they have a duty to send it to the election court. They don't have any discretion to prevent it from going."

The distinction matters. Under Jamaica's electoral law framework, the Constituted Authority serves as a screening mechanism—receiving complaints and determining whether they contain sufficient credible evidence to warrant full investigation by the Election Court, which is established under Section 35(1) of the Election Petitions Act specifically to hear such cases and determine whether elections should be voided.

Buchanan's judicial review application argues that the Authority exceeded its mandate by not just screening the evidence but effectively adjudicating its sufficiency—asking themselves whether the evidence met the legal standard for voiding an election rather than whether it was credible enough to warrant investigation.

"The Respondent failed to appreciate that they were not acting as the election Court and that their duty is, that once there is evidence of election malpractice as established by the Applicant, they have a duty to refer the matter to the election Court," Buchanan's affidavit states.

The application further argues that the Authority "asked themselves the wrong question and concluded by making the wrong determination as to the evidence that was before them"—a textbook definition of the kind of procedural error that makes administrative decisions vulnerable to judicial review.

The Remedy Sought

Buchanan isn't asking the Supreme Court to overturn the election results directly. Instead, he's seeking several specific orders that would force the Constituted Authority to do what he believes they should have done in the first place: refer his complaint to the Election Court for proper adjudication.

His application seeks a declaration that the Authority's refusal was "unlawful, null and void and of no effect." He wants an order of certiorari quashing the Authority's decision. Most significantly, he seeks an order of mandamus—a court order compelling a public body to perform a duty it is legally required to perform—forcing the Authority to refer his application to the Election Court.

"We are asking the Supreme Court to intervene and to quash their decision and to compel them by way of a mandamus to send it to the election court, to consider whether the election in West Central [St. Andrew] should be voided," Wildman explained.

Implications Beyond One Constituency

While Buchanan's challenge focuses on one constituency and one election, the case raises broader questions about Jamaica's electoral oversight mechanisms. If the Constituted Authority can effectively determine the merit of election complaints rather than simply screening them for credibility, does that render the Election Court redundant in practice? Does it create a system where politically sensitive cases might be filtered out before receiving full judicial scrutiny?

These questions extend beyond partisan considerations. The integrity of electoral oversight systems depends on clear delineation of roles and responsibilities—who screens, who investigates, who adjudicates. When those lines blur, confidence in the entire system can erode.

For now, the matter rests with the Supreme Court, which must first grant Buchanan leave to proceed with his judicial review before the substance of his complaint can be heard. The legal process could take months, during which Holness will continue serving as both Prime Minister and the duly elected representative for St. Andrew West Central.

But Buchanan's challenge ensures that questions about what happened on election day in Olympic Gardens and Molynes Gardens—and who gets to decide if those questions deserve answers—will linger long after the votes were counted.

-30-