ST. LUCIA | Philip J. Pierre's Landslide Victory Shatters St. Lucia's Two-Decade Political Pattern

CASTRIES, St. Lucia, December 2, 2025 - When Philip J. Pierre stepped onto the verandah of his Castries East constituency office just before 10 p.m. Monday night, he wasn't just celebrating another victory. He was presiding over the demolition of St. Lucia's political status quo—a 24-year pattern that had made the island a graveyard for incumbent governments.

The numbers tell a brutal story. The Saint Lucia Labour Party didn't just win reelection; it crushed the opposition United Workers Party into near-oblivion, securing 14 seats to the UWP's solitary victory. Adding the two independents who served in Pierre's outgoing Cabinet—Richard Frederick and Stephenson King—the government commands a supermajority that would be the envy of any regional leader.

This is the first time since 2001 that any party has won consecutive general elections in St. Lucia. More remarkably, it's the first time since independence that an incumbent government has actually improved its performance when seeking a second term. Pierre didn't just break the curse—he shattered it with a sledgehammer.

The Opposition's Existential Crisis

For UWP leader Allen Chastanet, Monday night represented political annihilation. His party, which governed from 2016 to 2021, now holds just one seat—his own. Even Bradley Felix, one of only two UWP MPs going into the election, lost his Choiseul constituency to Labour's Keithson Charles. The result ties the UWP's worst-ever performance, matching its 1997 debacle.

The scale of defeat raises uncomfortable questions about the health of St. Lucia's democracy. While Pierre spoke graciously of ensuring "a place in Parliament for the opposition," the reality is that meaningful opposition requires more than a single voice in a 17-member chamber. Can one MP effectively scrutinize government policy, challenge legislation, or hold ministers accountable? The answer is self-evident—and troubling.

This isn't just about the UWP's organizational failures or Chastanet's leadership struggles. It's about whether St. Lucia now faces the prospect of one-party dominance, where the governing party's internal dynamics matter more than electoral competition. The very cycle Pierre broke—throwing out governments after one term—served as a crude but effective accountability mechanism. What replaces it?

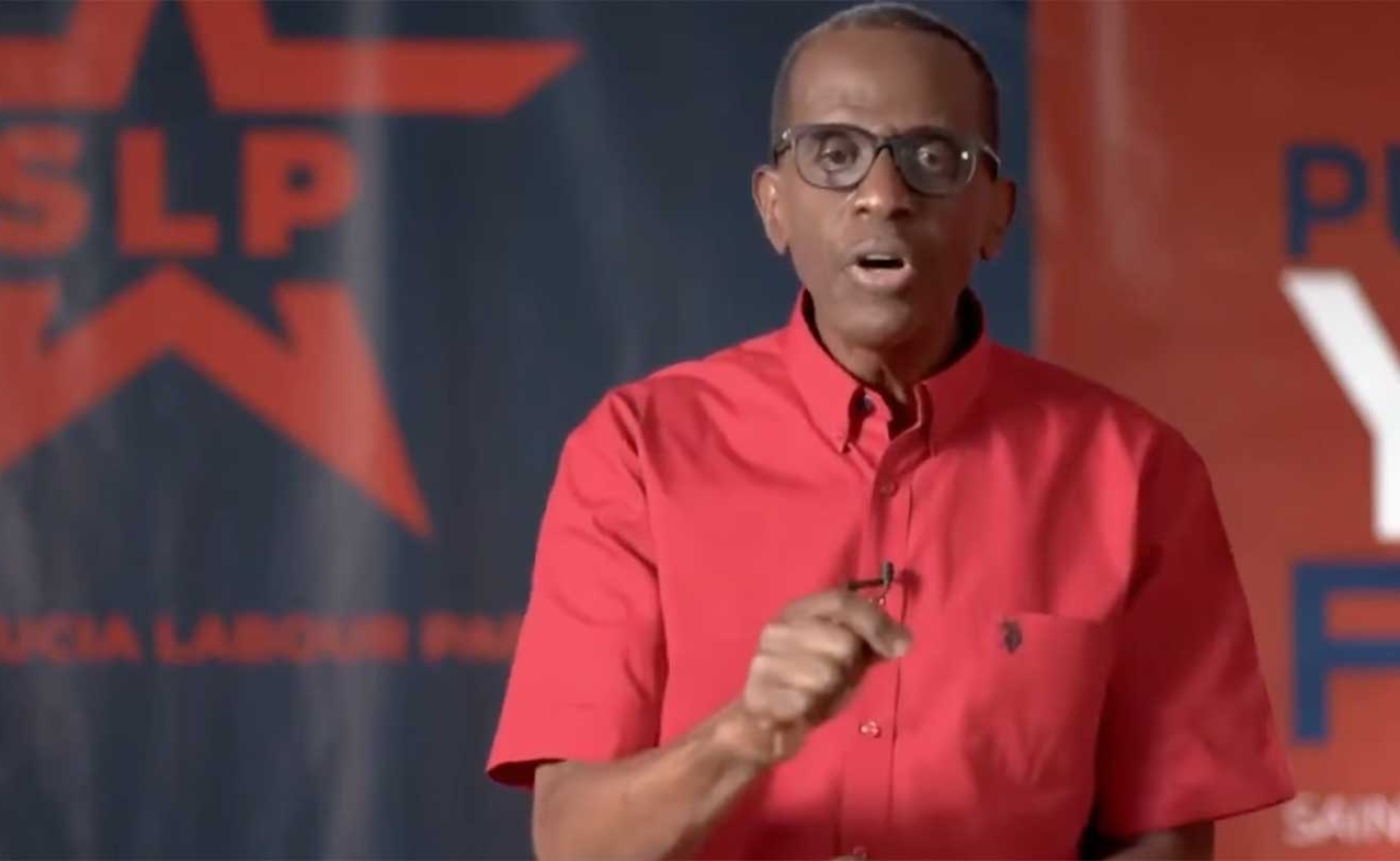

The Victor and the Vanquished: Prime Minister Philip Pierre re-elected for a second term and Opposition leader Allen Chastenet winning only his seat in parliamentThe Personal Toll of Political Combat

The Victor and the Vanquished: Prime Minister Philip Pierre re-elected for a second term and Opposition leader Allen Chastenet winning only his seat in parliamentThe Personal Toll of Political Combat

Pierre's victory speech revealed the scars beneath the triumph. His voice carried particular weight when he lamented the "depth" St. Lucian politics had reached over "the last four and a half years," especially the attacks endured by his daughter. "I hope that no opposition party ever stoops to those limits," he said—a rebuke that suggests the campaign descended into territory that even seasoned politicians found shocking.

Yet Pierre also spoke of ending an era of "lies and misinformation," framing his mandate as not just policy validation but moral vindication. This dual messaging—condemning opposition tactics while celebrating their defeat—reflects the tension inherent in overwhelming victory. How does a leader call for unity and reconciliation when the electorate has rendered such decisive judgment against his opponents?

The Mandate's Implications

For Pierre personally, this represents extraordinary political longevity. His seventh consecutive term representing Castries East, combined with his rise from Cabinet minister under Kenny Anthony to Prime Minister, marks him as one of St. Lucia's most durable political figures. Some supporters have been with him since his first campaign in 1997—a 28-year political partnership that speaks to deep personal loyalty beyond party machinery.

The immediate agenda signals continuity: a VAT-free day, public servant back pay, keeping "this country on the right trajectory." These aren't revolutionary promises but the language of competent administration—exactly what voters endorsed by breaking the single-term pattern.

A Regional Anomaly

Pierre's victory stands out in a Caribbean context where incumbent governments often struggle for reelection. While Jamaica recently bucked this trend with Andrew Holness's JLP winning successive terms, single-term governments remain common across the region. St. Lucia's 24-year cycle was extreme, creating political instability masked as democratic vigor.

Breaking that cycle offers potential benefits: policy continuity, institutional stability, and the ability to implement long-term development strategies without constant political disruption. But it also eliminates the regular housecleaning that prevents complacency and corruption from taking root.

As Pierre prepares for his swearing-in later this week and Cabinet appointments next week, St. Lucia enters uncharted territory. The mandate is clear, the opposition is decimated, and the path forward is Pierre's to define. Whether this becomes a story of consolidated governance or democratic atrophy depends largely on how the Prime Minister wields his overwhelming power—and whether the UWP can rebuild itself into something resembling viable opposition.

The cycle is broken. What comes next will determine whether that's cause for celebration or concern.

-30-