GHANA | While Africa Honors Nkrumah, Ghana Honors Kotoka, His Betrayer

ACCRA, Ghana, May 25, 2025- Calvin G. Brown— Every visitor to Ghana's capital is greeted by a profound historical betrayal. The gleaming sign at Kotoka International Airport bears the name of the very man who orchestrated the downfall of Ghana's founding father, creating a bitter irony that cuts to the heart of the nation's identity crisis.

If Ghanaian President John Dramani Mahama is truly committed to building a legacy of effective governance that no future administration will be able to undo, he should explore the possibility of renaming the airport. Such a move would represent more than political symbolism—it would signal Ghana's readiness to finally confront a historical injustice that has festered for nearly six decades.

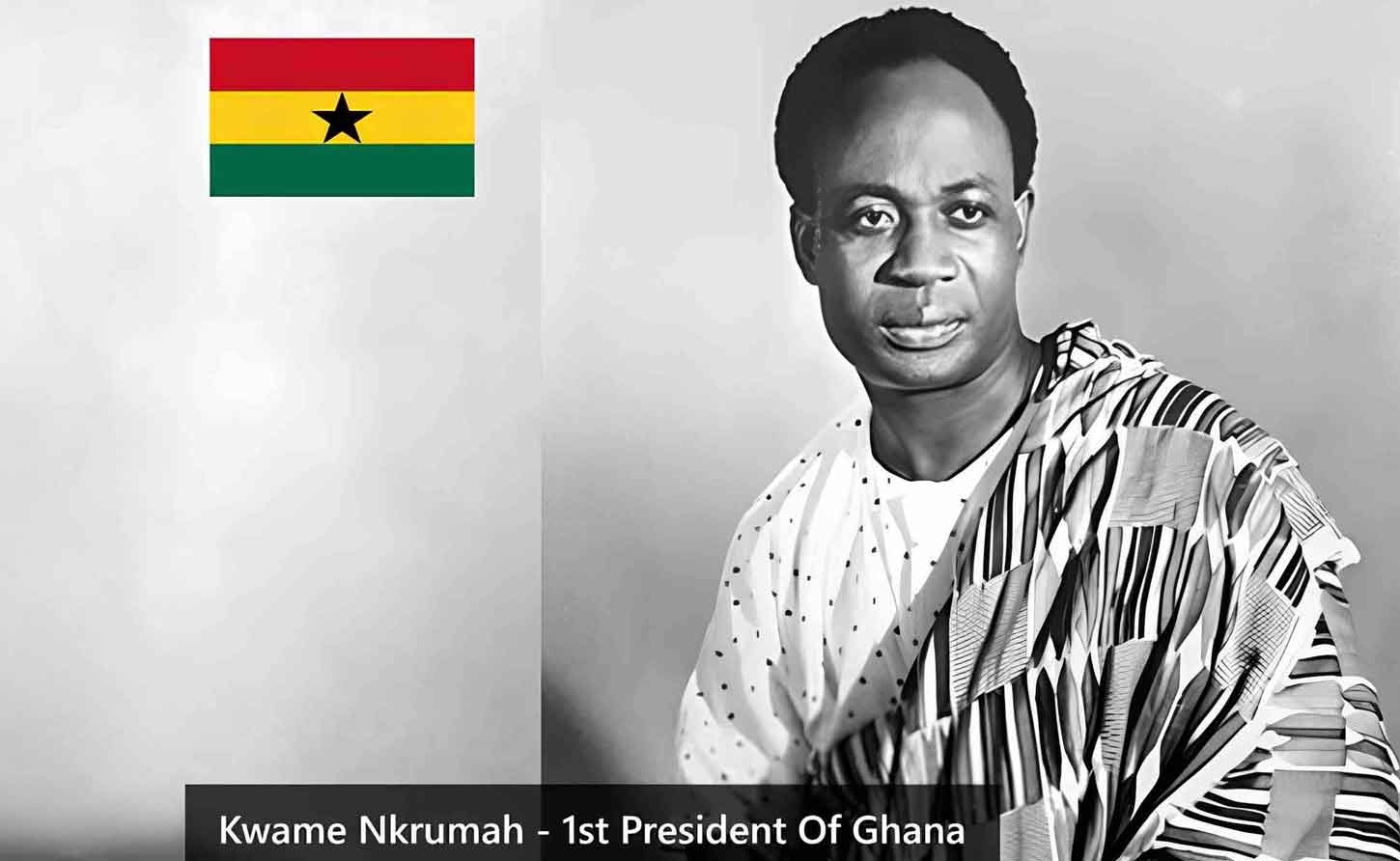

In a twist that would make colonial administrators smile from their graves, Ghana's primary gateway to the world honors Lt. Gen. Emmanuel Kwasi Kotoka—the coup leader who toppled Kwame Nkrumah in the first bloody coup d'état in Ghana on 24 February 1966 which brought an end to the first republic of Ghana—rather than the visionary who led the Gold Coast to independence and became Africa's most influential Pan-Africanist. This isn't merely poor judgment; it's a deliberate erasure of liberation history that continues to wound Ghana's soul.

“ While Nkrumah is revered across the continent as a founding father of modern Africa, Ghana paradoxically honours the man who destroyed his life's work. ”

The contradiction strikes visitors immediately upon arrival. Here stands an airport named after a man whose defining act was to destroy the dreams of African unity and self-reliance, serving as the first impression of a nation that seemingly celebrates its own subjugation. Meanwhile, Nkrumah—the architect of Ghana's freedom and champion of continental liberation—remains conspicuously absent from this symbolic space.

Nkrumah's legacy towers over African history like a colossus. He didn't just lead Ghana to independence; he embodied the continent's deepest aspirations for self-determination, industrial advancement, and Pan-African unity. His vision extended far beyond Ghana's borders, inspiring liberation movements across Africa and the diaspora while challenging the global order that kept Africa economically shackled to its former colonizers.

Kotoka, by contrast, represents everything Nkrumah fought against. His 1966 military coup didn't just remove a president—it shattered the Pan-African dream and redirected Ghana back toward the Western orbit that Nkrumah had worked so hard to escape. The coup marked a devastating setback for African unity and control over the continent's vast resources, echoing the tragic pattern that would plague post-independence Africa for decades.

This historical revision reflects a broader tragedy across post-colonial Africa, where genuine freedom fighters were systematically replaced in the popular imagination by those who served foreign interests. From Mobutu Sese Seko in Zaire to Idi Amin in Uganda, the continent became littered with monuments to men who betrayed the very liberation struggles that brought them to power. Ghana's airport naming follows this shameful pattern, celebrating collaboration over courage.

The absurdity becomes even more stark when considering how the rest of Africa views these two figures. While Nkrumah is revered across the continent as a founding father of modern Africa, Ghana paradoxically honors the man who destroyed his life's work. It's as if the United States had named its capital's airport after Benedict Arnold instead of George Washington.

Today, as Ghana grapples with economic challenges that echo the dependency issues Nkrumah warned against, the airport's name serves as a daily reminder of roads not taken. Every flight that departs carries passengers past a symbol of historical amnesia, while the vision of the man who dreamed of African airlines connecting a truly independent continent gathers dust in history books.

The call to rename Kotoka International Airport as Nkrumah International Airport isn't about settling old scores—it's about Ghana finally telling the truth about itself. It's about acknowledging that the struggle for independence wasn't completed in 1957 but was brutally interrupted in 1966, and that the nation still owes its founding father the recognition he deserves.

Such a renaming would represent more than symbolic justice. It would signal Ghana's readiness to reclaim its revolutionary heritage and recommit to the principles of self-reliance, African unity, and genuine independence that Nkrumah championed. In a continent still struggling with neo-colonial dependency, Ghana could lead by example, showing that it's never too late to honor the right heroes.

The airport that greets visitors to Ghana should bear the name of the man who made Ghana possible, not the one who nearly destroyed it. Until that day comes, every arrival in Accra will carry the sting of historical betrayal—a constant reminder that Ghana has yet to fully embrace the liberation legacy that should be its greatest source of pride.

As a footnote, It was Kotoka who announced the coup to the nation early that fateful February morning from the Broadcasting House of the Ghana Broadcasting Corporation, the official radio station in Ghana. The Central Intelligence Agency appears to have been aware about the plotting of the coup at least a year ahead.

On the day of the coup in 1966, Kotoka was promoted to Major General and became a member of the ruling National Liberation Council and also the Commissioner for Ministry of Health as well as General Officer Commanding the Ghana Armed Forces.

On the first anniversary of the coup, February 24, 1967, he was promoted to the rank of Lieutenant General.

The author calls for a national conversation about Ghana's historical memory and the importance of honoring genuine liberation heroes over those who served foreign interests.

-30-