Jamaica | Desecrating Our Heroes: A Betrayal of Jamaica's Soul

MONTEGO BAY, Jamaica - "A people without knowledge of their past is like a tree without roots," Marcus Garvey once warned. Today in Montego Bay, those roots are being severed by our own hands.

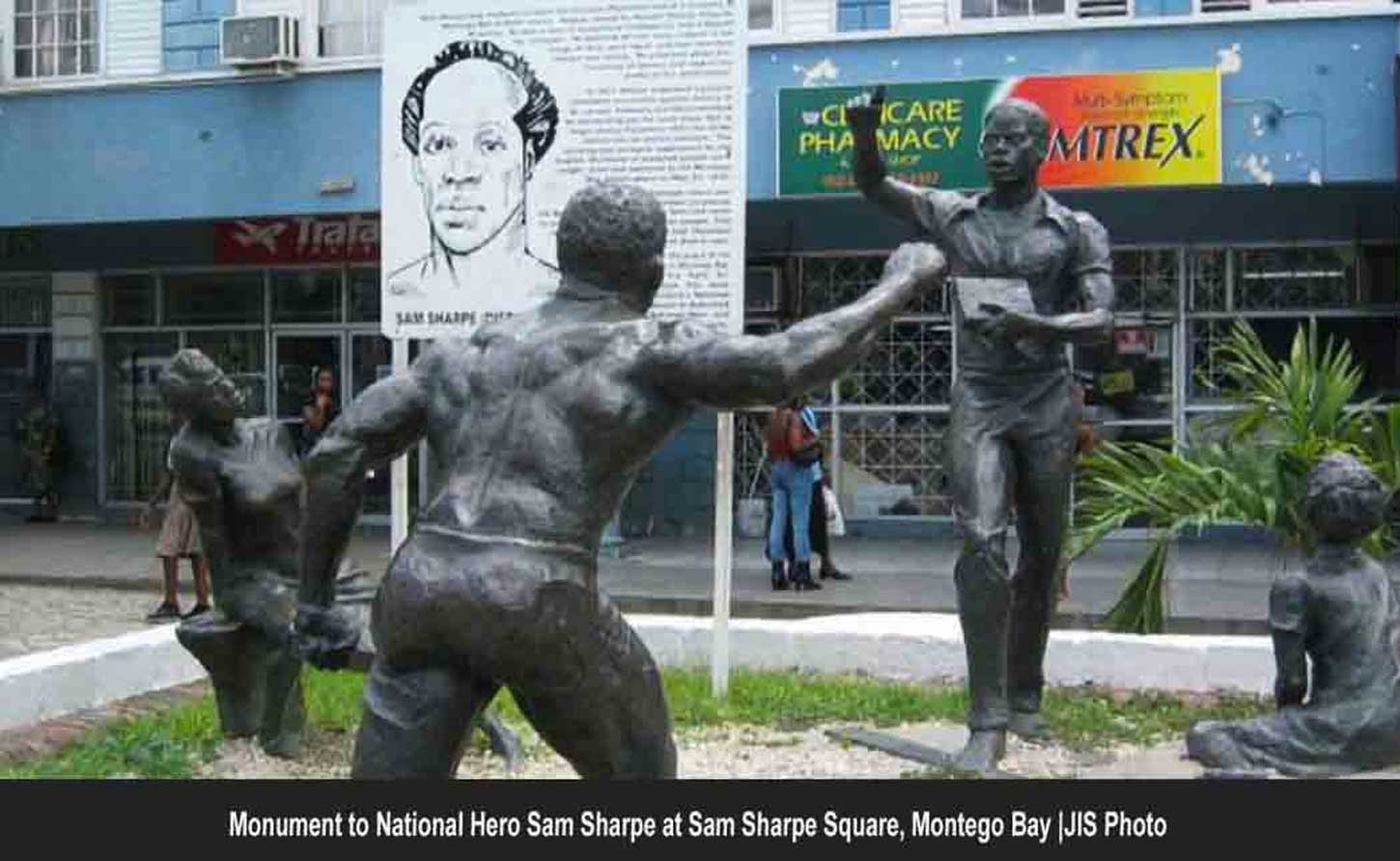

The morning news struck like a thunderbolt—bronze statues commemorating national hero Samuel Sharpe and his fellow freedom fighters had been defaced at Sam Sharpe Square.

For anyone who cherishes Jamaica's hard-won independence, this represents more than mere vandalism; it is a national wound, a self-inflicted erasure of our collective memory.

My 18-year-old niece recently remarked, "These cannot be the same Jamaicans Marcus Garvey fought and was persecuted for." This morning's news forces us to confront her observation with painful clarity.

As a student of history and a patriotic Jamaican, I cycled through rage, disbelief, and profound sorrow.

My initial reaction was visceral, but rage eventually gave way to reflection: When did we get here? How did we get here?

We inhabit the Information Age, where knowledge dances at our fingertips. Gone are the days of trekking through libraries and combing through encyclopedias.

With a keystroke, we can summon centuries of wisdom in seconds. Yet somehow, we find ourselves drowning in an ocean of information while dying of thirst for genuine knowledge.

Our educational system bears some responsibility. History classes dutifully taught in our schools often gloss over the "difficult" aspects of our story.

What I now know about Jamaican, Caribbean, and African history was largely acquired outside traditional academic settings—through reading, an apparently endangered practice.

Like many, I received only the cliff notes version of slavery, an oversimplified retelling of the Haitian Revolution, and a sanitized account of the "Christmas Rebellion" that fails to capture their profound impact on the abolition of slavery.

Samuel Sharpe—the man whose memorial now stands defaced—was no footnote in history. He was the brilliant architect behind the 1831 Slave Rebellion that began on Kensington Estate in St. James. A man of such remarkable intelligence and leadership that he earned the title "Daddy Sharpe" among native Baptists in Montego Bay.

In a time when religious gatherings were the only permissible form of organized activities for enslaved people, Sharpe transformed these meetings into incubators of political consciousness. There, he shared news of events in England that affected Jamaica's enslaved population and cultivated a revolutionary vision.

By 1831, he had developed a plan of passive resistance—a strategic refusal to work beginning Boxing Day unless their demands for better treatment and consideration of freedom were acknowledged.

With sacred solemnity, Sharpe shared his plan with chosen supporters after religious meetings, binding them to secrecy and solidarity with a kiss on the Bible. The vision spread through St. James, Trelawny, Westmoreland, and beyond. But as with most planned rebellions, betrayal lurked in the shadows. Some who preferred the certainty of bondage to the uncertainty of freedom whispered the plan to plantation owners.

When December 27, 1831 arrived, the Kensington Estate Great House erupted in flames—a signal that the war had begun. As fires multiplied across the region, it became clear that Sharpe's vision of non-violent resistance had transformed into something more urgent and direct.

When December 27, 1831 arrived, the Kensington Estate Great House erupted in flames—a signal that the war had begun. As fires multiplied across the region, it became clear that Sharpe's vision of non-violent resistance had transformed into something more urgent and direct.

Armed warfare spread primarily through western parishes until British military forces, with their superior firepower, suppressed the ill-equipped enslaved warriors in early January.

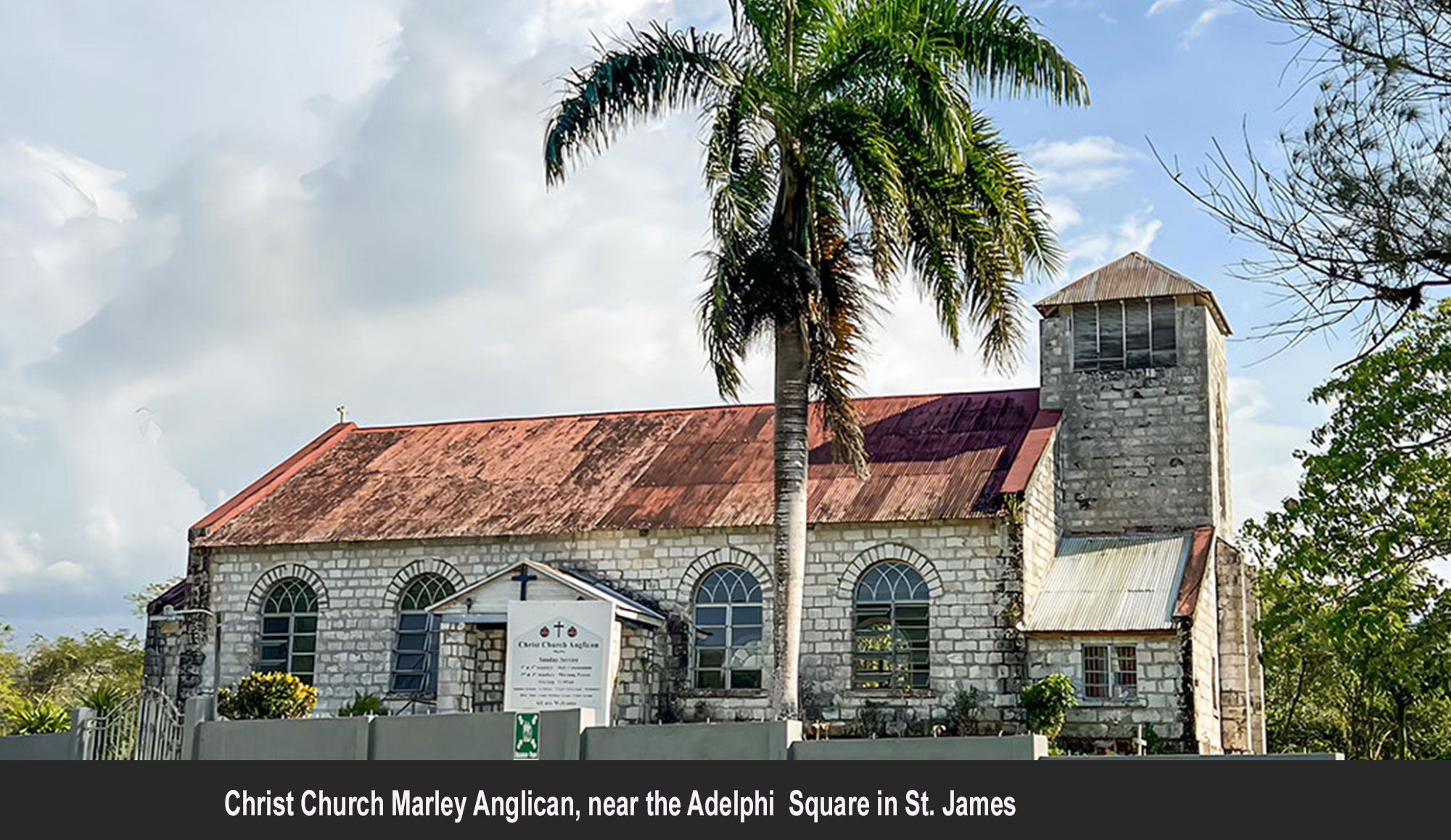

The retribution was swift and merciless. While 14 white colonists died during the rebellion, more than 500 enslaved people lost their lives—most after sham trials designed not for justice, but vengeance. After the Sam Sharpe war of 1831-32, over 200 enslaved black women and men were rounded up and shot in cold blood in the square at Lima, near Adelphi in St James.

No other bloodshed in both the colonial and modern history of Jamaica ever came close to the 'Infamy at Lima.' The ruling planter class attempted to cover up this vigilante mass murder, which went unnoticed for many years until scholars began to unearth our 'hidden heritage.'

Interestingly enough, during that mass murder, religious services were suspended at the Anglican church at Adelphi , as the church building was used as a military barracks and a jail.

Samuel Sharpe himself was hanged on May 23, 1832, his final words echoing through time: "I would rather die upon yonder gallows than live in slavery." Two years later, the British Parliament passed the Abolition Bill of 1834, and by 1838, slavery was abolished throughout the British Empire.

Sharpe's rebellion transformed into a war against the system, had become the proverbial straw that broke the back of centuries-old chattel slavery in the British Empire, directly precipitating abolition across the Caribbean and African colonies.

Now, in March 2025, those same statues stand defaced, and the ancestors weep. What could possibly be gained by such profound disrespect? We proudly wrap ourselves in black, green, and gold, thumping our chests at the slightest hint of disrespect toward anything Jamaican. We display our colors during times of collective celebration, but what happens when "the tour bus park and all lights lock off" and the world's eyes turn elsewhere?

This desecration reflects a deeper erosion of patriotic, civic pride. The question isn't just about vandalized statues—it's about who we are becoming as a people. Do we live our professed pride and respect in our daily actions? How many of us dispose of our garbage properly rather than flinging it anywhere convenient?

While the National Solid Waste Management Authority faces serious challenges, we must focus on what we as individuals can control—the things we can collectively do to make Jamaica truly the place of choice.

We lament the derelict state of societal norms and values, forgetting that WE are the society. WE dictate the values and attitudes. The once-omnipresent village that raised our children has been betrayed by the villagers themselves. "Mi nuh want no-baddy fi reprimand mi pickney," declare some parents, while others storm schools to "deal wid di dutty teacher" in full view of their children. Children live what they learn.

I once dismissed my elders' reminiscences about days when people respected authority and honored the sacred as mere nostalgia. But I came to understand the value of those lessons, practiced them, and passed them on to my nieces and nephews. Unfortunately, not everyone understood the assignment, and preserving societal values is unquestionably group work.

WE are the architects of our own demise, yet we blame the ubiquitous 'THEY' as though our actions and inactions played no role in shaping today's Jamaica. We've created a society where the average person doesn't know what a poppy symbolizes, where children and adults show no respect for authority or each other, where stepping on someone's Clarks warrants a death sentence, where a Sam Sharpe monument is desecrated without a second thought.

Those seemingly insignificant transgressions—forgetting the Golden Rule, discarding civic responsibility—snowball into the erosion of our society's foundation and our identity as Jamaicans. In short, WE are either the change we seek or the agents of our own destruction. The choice is ours. The ancestors are watching.

-30-