JAMAICA | “PocoMania”: British Colonials Weaponized Psychiatry Against Alexander Bedward

By Calvin G. Brown

MONTEGO BAY, Jamaica, December 23, 2025 - Social and political commentator O. Dave Allen has done Jamaica a profound service by directing our attention back to Alexander Bedward—not the cartoonish "flying lunatic" of popular memory, but the formidable anti-colonial leader who commanded 30,000 followers across 125 congregations spanning Jamaica, Cuba, and Central America.

Allen's reminder arrives at a crucial moment when we must finally confront an uncomfortable historical truth: Bedward was not mad. His incarceration in the Kingston Lunatic Asylum was a calculated political weapon deployed by British colonial authorities who learned from their previous mistakes that creating martyrs through execution only amplified Black resistance.

The question we must ask is not whether Bedward was insane, but rather: what kind of society declares its most threatening critics mentally ill and locks them away where their words can be dismissed as the rants and ravings of a madman?

The Threat That Couldn't Be Ignored

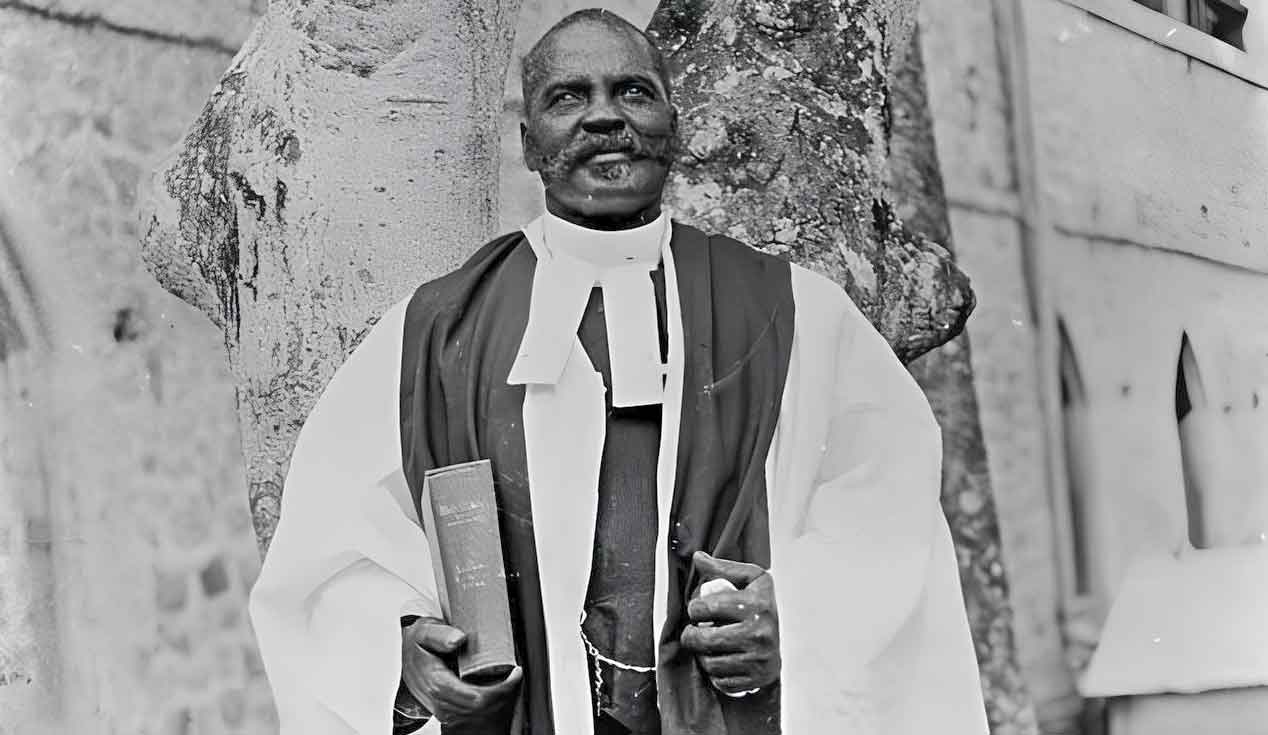

To understand why colonial authorities resorted to psychiatric incarceration, we must first appreciate the magnitude of the threat Bedward posed. This was no fringe religious figure speaking to a handful of followers in a backwater parish.

By the movement's height, Bedwardism encompassed a hierarchical organization throughout Jamaica, with a demographic composition that represented precisely those whom the colonial order most feared: the Black, disaffected rural peasantry and working classes who formed the dominant majority of Jamaica's population.

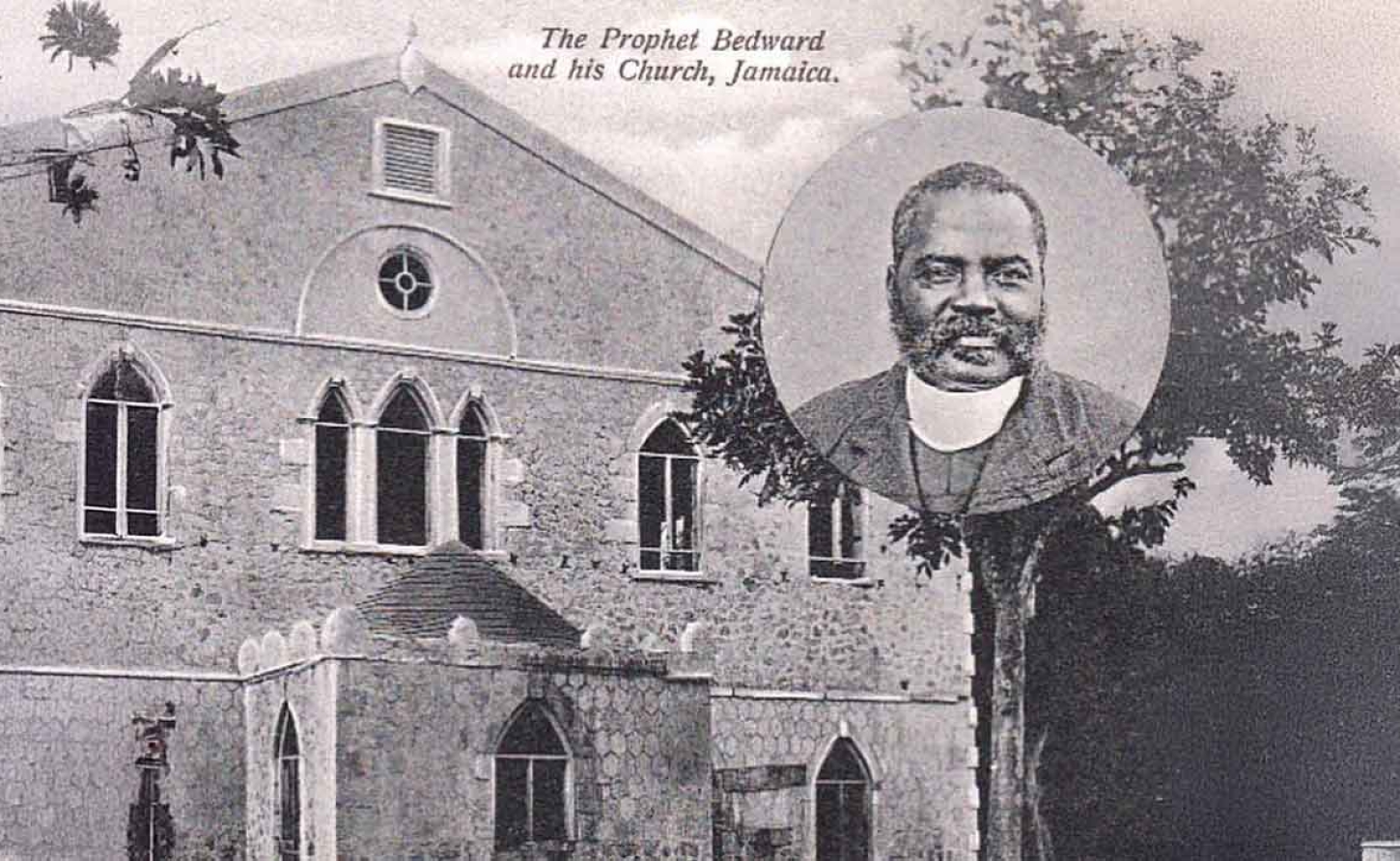

From his base at August Town, where he established the Jamaica Native Baptist Free Church on the banks of the Hope River in 1891, Bedward constructed something far more dangerous than a church.

"There is a white wall and a black wall, and the white wall has been closing around the black wall; but now the black wall has become bigger than the white wall and they must knock the white wall down," he proclaimed in his most famous sermon. "The white wall has oppressed us for years; now we must oppress the white wall."

He called the governor a "scoundrel and a robber," declared the government "thieves and liars," and told his followers to "remember the Morant Bay Rebellion"—invoking Paul Bogle's 1865 uprising that colonial authorities had brutally crushed just three decades earlier. He reimagined sacred geography itself, positioning August Town as corresponding to biblical Jerusalem, asserting that divine favor rested not with European empires but with Jamaica's Black poor.

This was sedition in the clearest sense—not because Bedward was delusional, but because he was dangerously coherent. He offered Jamaica's oppressed majority a counter-narrative to colonial ideology, a theological justification for resistance, and a organizational structure capable of mobilizing thousands.

The cut-stone church his followers built—91 feet long, 61 feet wide, 24 feet high—stood as physical testament to the movement's resources and commitment. The tri-weekly fasts, quarterly baptisms, and regular Sunday services that drew pilgrims from across Jamaica demonstrated organizational sophistication that rivaled any political party.

Colonial authorities faced a dilemma. They could not ignore Bedward. But how could they silence him without repeating their catastrophic mistakes?

Learning From Martyrs: The Psychiatric Solution

The British colonial administration in Jamaica had, by 1895, learned painful lessons about what happens when you execute charismatic Black leaders. Sam Sharpe, hanged in 1832 after leading the 1831 Sam Sharpe War, also called the 'Christmas Rebellion,' became an enduring symbol of resistance. Paul Bogle, executed in 1865 after Morant Bay, was virtually expelled from the national psyche during colonial rule precisely because authorities recognized his martyrdom as a rallying point for future resistance.

Execute Bedward, and you create a martyr whose death validates his message and inspires further resistance. Acquit him, and you legitimize his seditious preaching. Imprison him, and he becomes a political prisoner whose continued incarceration reminds followers of colonial injustice.

The solution colonial authorities devised was both cynical and brilliant: declare him insane.

In 1895, following his "white wall/black wall" sermon, they charged Bedward with attempting to cause "insurrection, riots, tumults, and breach of the peace." But the sedition trial was a predetermined charade. After just one day of proceedings, the jury deliberated for forty minutes before delivering a verdict that solved the colonial government's problem: not guilty by reason of insanity.

Read that verdict again. Not guilty—meaning they couldn't prove he committed sedition. But insane—meaning everything he said could be dismissed as the delusions of a madman.

But the damage was done. The colonial state had established the precedent that Bedward's political challenge to white supremacy was evidence of mental illness rather than legitimate grievance.

Scholar Dave St. Aubyn Gosse's 2022 analysis makes the strategy explicit: "Jamaica's colonial laws—most notably the lunacy and vagrancy acts—were devised to stifle all expressions of African folk culture and were instituted as a response to Bedwardism." The psychiatric institution became what Professor Frederick W. Hickling of the University of the West Indies describes as "an extension of slavery," staffed by "Britons doing Colonial Service, carrying out the 'civilizing mission' of the British Empire."

Hickling's language is deliberately stark: European "moral treatment" in colonial asylums was "a disingenuous obfuscation of slavery," he argues, "camouflaging a racist melange of European paternalistic psychotic delusions of ownership and control."

The irony is profound. The truly psychotic delusion was the colonial belief in racial hierarchy and the right to rule over Black populations. Yet it was Bedward, challenging that delusion, who was institutionalized as mad.

The Media Accomplice: Manufacturing the Lunatic

Colonial psychiatry required a accomplice to cement Bedward's transformation from political threat to laughingstock, and Jamaica's establishment newspaper, the Daily Gleaner, enthusiastically volunteered for the role.

Throughout Bedward's ministry, the Gleaner maintained consistently hostile coverage, reinforcing what academic analysis describes as "racialized codes of difference." The newspaper celebrated how "calmness and clemency" were used against the "ignorance and momentary ebullitions of primitive passion" represented by Bedwardism. The framing expressed explicit concern that the movement undermined Jamaica's "civilising" claims—the colonial fiction that British rule was elevating backward natives.

The Gleaner's most damaging contribution came after the 1920 gathering where Bedward predicted his ascension to heaven. The mocking headline—"Bedward Stick to the Earth"—became emblematic of how colonial media transformed a religious leader into a figure of ridicule. Yet as the Jamaica Observer noted in 2021, "there is no record of any attempt by Bedward or his followers to fly. Neither did he or his followers sustain any injuries in any such attempt."

Critically, if Bedward had actually attempted to physically fly, colonial authorities and the Gleaner—which maintained intense surveillance of him—would have certainly used it as ammunition to discredit and ridicule him in official charges and court proceedings. They did not.

The "flying lunatic" narrative appears to be largely posthumous fabrication, embellished or invented to render Bedward ridiculous rather than threatening. But the Gleaner's sustained campaign of mockery achieved its purpose. As UWI Press notes in describing Gosse's recent book, "Laughter is the natural response of most Jamaicans to the name Alexander Bedward, long proclaimed as the lunatic who literally attempted to fly to heaven."

Laughter—the perfect antidote to political mobilization. You cannot organize around a joke. You cannot take seriously the teachings of someone whose name triggers giggles. The colonial media succeeded where courts and asylums alone could not: they transformed Bedward from prophet to punchline.

Bedward was sentenced to be incarcerated at the Bellevue psychiatric Lunatic Asylum in Kingston where he spent nine years until his death in 1930.

Bedward was sentenced to be incarcerated at the Bellevue psychiatric Lunatic Asylum in Kingston where he spent nine years until his death in 1930.

Scholar Anthony Bogues captured the truth with precision: Bedward's only "insanity" was his attempt to "break and reorder the epistemological rationalities of colonial conquest." In plain language: he was crazy enough to believe that Black Jamaicans deserved dignity, justice, and self-determination. He was insane enough to think divine favor might rest with the oppressed rather than the oppressor. He was delusional enough to imagine that August Town could be as sacred as Jerusalem.

These were dangerous ideas—not because they were false, but because they were true.

Bedward's influence extended far beyond his lifetime. Marcus Garvey himself positioned Bedward as "Aaron to Garvey's Moses." Many Bedwardites became Garveyites, bringing with them experience in resisting the system and community organization. Robert Hinds, one of Rastafari's founders and Leonard Howell's second-in-command, was a Bedwardite arrested during Bedward's 1921 march. The progression is documented by scholars: from Bedward through Garvey to Rastafari—each building on the foundation of the previous movement.

The Jamaica National Heritage Trust declared Bedward's church a national monument in 1999, and campaigns continue for his recognition as a National Hero. Contemporary MP André Hylton acknowledged the historical injustice: "He was maligned by the system, the colonial masters, the Church and the media. We must now tell the true story."

—30—