JAMAICA | Come Home to What? Jamaica's Diaspora Nurse Recruitment Masks a Healthcare System in Freefall

A glossy recruitment poster cannot hide a decade of institutional collapse, from Cornwall's $23.5 billion scandal to KPH's mould-infested operating theatres

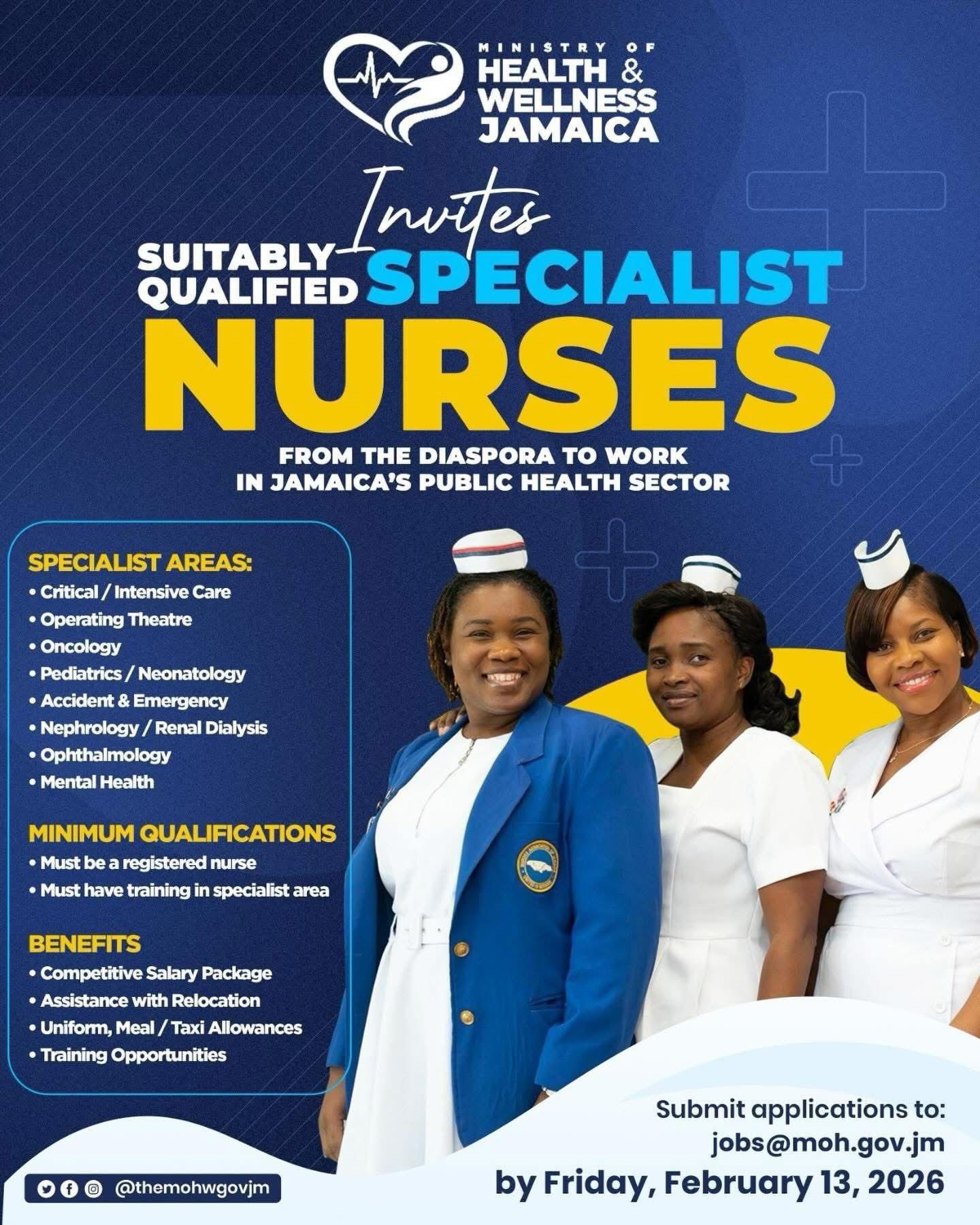

KINGSTON, Jamaica, January 9, 2026 — The Ministry of Health and Wellness wants you to come home. In a recruitment poster featuring three nurses in crisp whites and traditional caps, Jamaica is inviting its diaspora nurses to return. Specialist positions in Critical Care, Oncology, A&E, Mental Health. Competitive salaries. Relocation assistance. Applications due February 13, 2026.

For decades, Jamaica trained nurses for wealthier nations. America, Britain, and Canada reaped the harvest. Now, suddenly, the government finds resources to compete for its own talent.

The deadline approaches. The questions multiply. And the hospitals these nurses would return to are falling apart.

A System in Collapse

Cornwall Regional Hospital—western Jamaica's primary facility serving Montego Bay—has been under repair since 2016. Originally estimated at $2 billion with completion by September 2018, the cost now stands at $23.5 billion—an increase exceeding 1,000 percent.

Cornwall Regional Hospital—western Jamaica's primary facility serving Montego Bay—has been under repair since 2016. Originally estimated at $2 billion with completion by September 2018, the cost now stands at $23.5 billion—an increase exceeding 1,000 percent.

After a decade of construction chaos, what reopened in April 2025 was merely the administrative block. Not wards. Not operating theatres. Not A&E. Office space.

Former Opposition Senator Janice Allen was unsparing: "After eight years and a cost jump from $2 billion to $23 billion, what the people of western Jamaica deserve is healthcare, not headlines."

Kingston Public Hospital—the nation's largest, serving 90,000 A&E cases annually—fares little better. In April 2025, its four main operating theatres closed for mould remediation. One month later, A&E shut down due to a chemical leak.

Dr Tufton's own assessment was telling: "We need to avoid a second Cornwall Regional Hospital."

Spanish Town Hospital's A&E flooded during heavy rains. St. Ann's Bay, Annotto Bay, Savanna-la-Mar—the litany of struggling facilities stretches across parishes. This is the healthcare system asking diaspora nurses to come home.

The Cuban Shadow

In March 2025, US Secretary of State Marco Rubio stood in Kingston and delivered a thinly veiled ultimatum. Cuban medical personnel represent "forced labour," he declared. Countries participating in these programs could face visa restrictions.

Jamaica hosts over 400 Cuban medical professionals who help keep the struggling system functioning.

Prime Minister Holness pushed back publicly: "The Cuban doctors in Jamaica have been incredibly helpful to us. Jamaica has a deficit in health personnel, primarily because many of our health personnel have migrated to other countries."

But diplomatic defiance is one thing. Contingency planning is another.

This recruitment drive—launched months after Rubio's visit—reads less like progressive healthcare policy than emergency preparation for an American-imposed exile of Cuban personnel.

The diaspora nurse recruitment may be Kingston's insurance policy against Washington's Cuba obsession.

The Arithmetic of Absurdity

Here is the central question: If Jamaica could afford "competitive salary packages" sufficient to lure nurses from First World healthcare systems, why haven't these salaries existed all along?

The nursing exodus wasn't a mystery. For decades, Jamaica trained nurses who left because local compensation couldn't compete. A US registered nurse earns $70,000-$90,000 annually. Jamaica's public sector salaries are a fraction of that. What changed?

One possibility: the money isn't coming from Jamaica's stretched budget. If American pressure to remove Cuban personnel comes attached to developmental assistance—or threats of consequences for non-compliance—the funding source becomes clearer. Washington has a long history of using aid to reshape Caribbean policy.

Another possibility: this recruitment drive is largely performative, designed to demonstrate Jamaica is taking steps toward self-sufficiency while navigating the US-Cuba diplomatic minefield.

Either way, the mathematics deserve scrutiny. Cornwall Regional consumed $23.5 billion and produced an administrative building. That sum could have funded competitive nursing salaries for years.

Beyond the Money

Opposition Spokesman on Health and Wellness Dr. Alfred Dawes crystallised what the Ministry's glossy advertisement fundamentally misunderstands:

Opposition Spokesman on Health and Wellness Dr. Alfred Dawes crystallised what the Ministry's glossy advertisement fundamentally misunderstands:

"For medical professionals who chose to leave Jamaica it was never just about the money. It's about the opportunities for professional development. It's about working in a well resourced environment where your efforts are respected and appreciated. It's about seeing your patients getting better because the resources are there for you to help them get better. Those conditions have not changed since they left Jamaica and until the powers that be understand this, more will continue to leave, not to return."

The advertisement promises relocation assistance and uniform allowances. It does not promise functioning operating theatres free of mould, or A&E departments that won't leak chemicals. It cannot promise that nurses will have the resources to actually help their patients get better.

The application deadline is February 13, 2026.

The hard questions remain unanswered.

And somewhere in a Kingston or Montego Bay A&E, a patient waits in a chair.

WiredJa is a Caribbean news organisation dedicated to centering regional perspectives on issues affecting the Caribbean and its diaspora.

-30-