CARICOM | Fiddling While Port-au-Prince Burns: Haiti's Leadership Crisis Reaches Breaking Point

CARICOM's pointed rebuke exposes a transitional government more interested in power struggles than the people it was created to serve—with regional leaders set to confront the fallout in St. Kitts next month

By CALVIN G. BROWN, WiredJa | January 27, 2026

In eleven days, Haiti's Transitional Presidential Council will cease to exist. Not because it accomplished its mission of stabilizing the nation and paving the way for democratic elections, but because its mandate simply expires on February 7th—a date that now looms like an epitaph over yet another failed chapter in Haiti's tortured political history.

The Caribbean Community's statement released today strips away any diplomatic niceties. CARICOM describes "internal turmoil taking place at the highest levels of the Haitian state" and labels the current situation "unacceptable."

For an organization that typically couches criticism in the softest possible terms, these words land like hammer blows.

The result is not resolution but paralysis: an "impasse" that CARICOM notes "renders more complex an already fraught governance transition process."

Translation: the people tasked with saving Haiti have succeeded only in making things worse.

The Only Winners Are the Gangs

While Haiti's nominal leaders engage in their Machiavellian maneuvers, the gangs that control an estimated 80 percent of Port-au-Prince continue their reign of terror.

CARICOM's statement contains a devastating observation that should shame every member of the TPC: the "current fragmentation works only for the benefit of the gangs."

This is the bitter truth that Haiti's political class refuses to internalize. Every day spent on internal power struggles is a day the gangs consolidate control.

Every failed vote to dismiss a prime minister is a victory for armed groups that have turned kidnapping into an industry and murder into routine.

The Haitian people—those experiencing what CARICOM calls "unimaginable violence and deprivation"—are not abstractions in a political game.

They are mothers who cannot send children to school, workers who cannot reach their jobs, patients who cannot access hospitals.

They are dying while their leaders fiddle.

The Clock Runs Out

What happens when the TPC's mandate expires? Who governs? Under what authority? The 3 April 2024 Political Accord that created this transitional arrangement offered no contingency for its architects failing so spectacularly.

CARICOM's Eminent Persons Group "remains at the disposal of all stakeholders," but disposal requires willing partners.

The multiplicity of proposals the statement references suggests everyone has a plan—and no one has consensus. This is governance by paralysis, democracy by deadlock.

Basseterre Beckons: A Regional Reckoning

The Haiti crisis will land squarely on the agenda when CARICOM Heads of Government convene for their Fiftieth Regular Meeting in Basseterre, St. Kitts and Nevis, on Tuesday, February 24th—just seventeen days after the TPC's mandate expires.

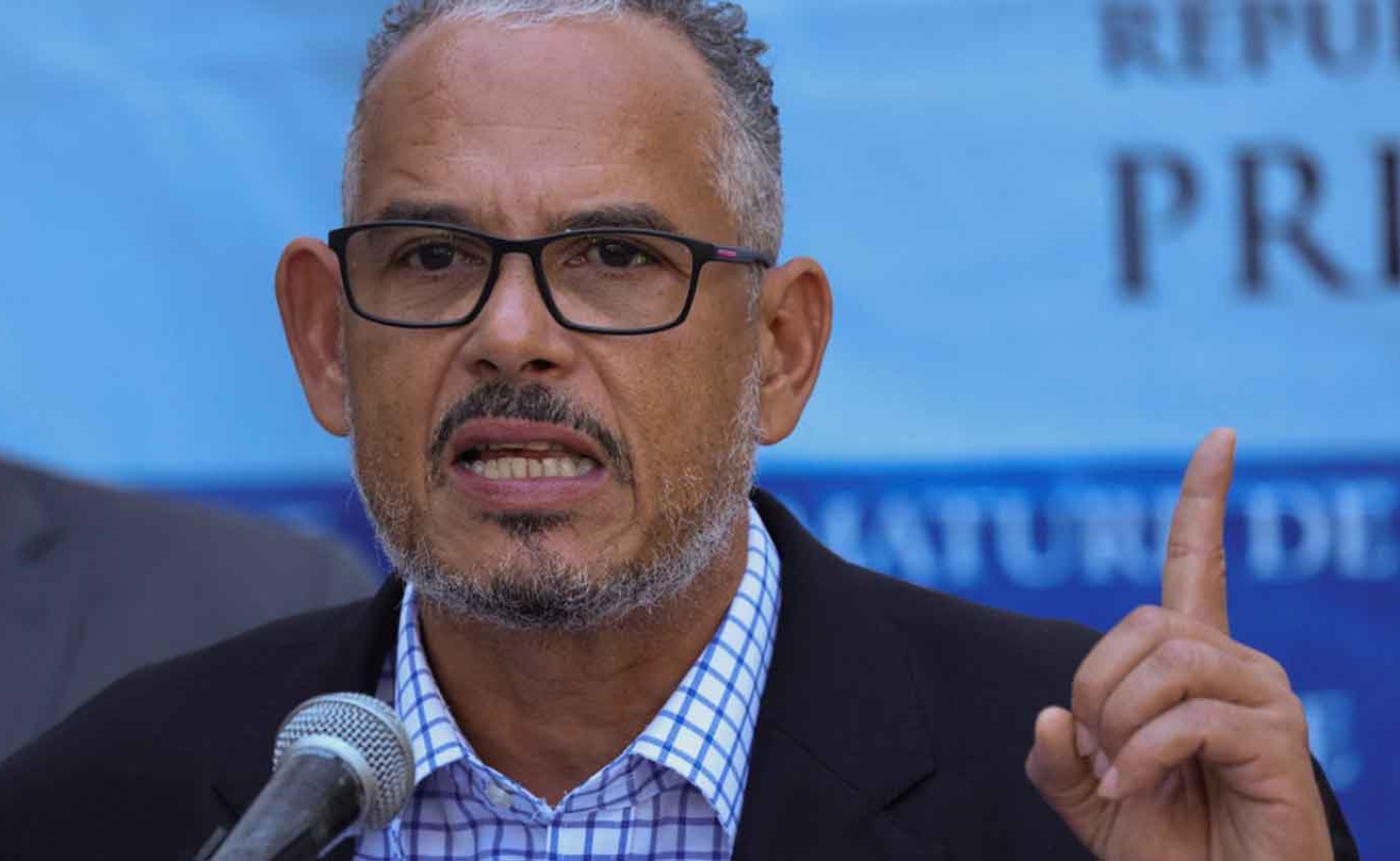

Current Chair Dr. Terrance Drew, Prime Minister of St. Kitts and Nevis, will preside over what promises to be one of the most consequential summits in the organization's history.

From February 25th to 27th, leaders and heads of delegations will gather at the St. Kitts Marriott to confront pressing global and hemispheric challenges.

The formal agenda encompasses the CARICOM Single Market and Economy, climate change financing, food and nutrition security, regional security, transportation, reparations, and foreign and community relations.

But hovering over every deliberation will be the unresolved question of Haiti—a founding CARICOM member state that may, by the time leaders arrive in Basseterre, exist in a governance vacuum.

The meeting's special guests—His Excellency Adel al-Jubeir, Minister of State for Foreign Affairs of Saudi Arabia, and Dr. George Elombi, President and Chairman of the Board of Directors of Afreximbank—underscore CARICOM's expanding global partnerships.

Yet these dignitaries will witness firsthand the limits of regional integration when one member state teeters on the brink of complete institutional collapse.

A Region Watching in Frustration

The Caribbean has invested heavily in Haiti's stability—not from altruism alone, but from recognition that regional security is indivisible.

A failed state in the heart of the Caribbean threatens migration patterns, drug trafficking routes, and the fundamental premise that small island nations can govern themselves effectively.

CARICOM's call for stakeholders to "act responsibly, and with urgency and patriotism" carries an undertone of exhaustion. How many statements must be issued? How many eminent persons must be dispatched? How many times must the region watch Haiti's leaders choose personal ambition over national survival?

The Haitian people deserve better than leaders who cannot agree on who should lead. They deserve better than a transitional government that has transitioned only into dysfunction. They deserve, at minimum, leaders who understand that eleven days from now, the music stops—and there may be no chairs left for anyone.

When Dr. Drew gavels open the Fiftieth Regular Meeting in Basseterre, he will face colleagues united in frustration and divided on solutions. The Caribbean Community's patience is not infinite. Neither is Haiti's capacity to endure leaders who have forgotten whom they were appointed to serve.

The gangs, at least, are paying attention.

-30-