CULTURE | Reclaiming the March: How Enslaved People Turned Sherman's Campaign Into Their Own Liberation Movement

UNITED STATES, August 10, 2025 - Every night, as Union campfires flickered across Georgia's war-torn landscape, Sally would begin her ritual. The formerly enslaved woman moved methodically through the camps, scanning faces in the dim light, searching for the children stolen from her years before.

Her nightly quest became so familiar that soldiers expected it, though many doubted she would ever find what she sought.

Yet Sally's determined march through Sherman's camps embodied something far more profound than personal hope—it represented the untold story of how enslaved people transformed a military campaign into their own emancipatory movement.

This is the narrative that historian Bennett Parten seeks to resurrect in his groundbreaking book "Somewhere Toward Freedom," a work that fundamentally challenges how Americans understand one of the Civil War's most decisive moments.

Sherman's March to the Sea, that devastating sweep through Georgia from November to December 1864, has long been remembered through the lens of white experience—either as heroic Union strategy or Confederate martyrdom.

But Parten argues we've been looking at the wrong protagonists entirely.

The General Who Changed Warfare

To understand the magnitude of what enslaved people accomplished, one must first grasp the formidable figure they chose to follow.

To understand the magnitude of what enslaved people accomplished, one must first grasp the formidable figure they chose to follow.

Union General William Tecumseh Sherman was one of the Civil War's most controversial and effective commanders—a man whose name still evokes passion across the American South more than 150 years later.

Sherman had risen through Union ranks as a strategic innovator who understood that winning the war required more than defeating Confederate armies; it meant breaking the South's will to fight.

By 1864, Sherman commanded the Military Division of the Mississippi and had proven his tactical brilliance in the capture of Atlanta, a vital Confederate transportation and supply hub.

But his next move would revolutionize modern warfare. Rather than pursuing retreating Confederate forces, Sherman proposed something audacious: cutting his army loose from supply lines and marching 300 miles to the Atlantic Ocean, living off the land while systematically destroying the South's capacity to sustain rebellion.

Sherman's "scorched earth" strategy targeted not just military installations but the entire infrastructure supporting the Confederate war effort—railroads, factories, plantations, and the civilian economy that fed and equipped Southern armies.

This was "total war" in its most ruthless form, designed to demonstrate to Southern civilians that their government could not protect them. Sherman himself famously declared his intention to "make Georgia howl."

When Sherman's 60,000 battle-hardened soldiers began their march from Atlanta on November 15, 1864, they were embarking on one of military history's most daring campaigns. But they would not march alone.

The Mythology We Inherited

For generations, Americans have understood Sherman's march through the distorted prism of "Gone With the Wind," where "the skies rained death" and noble plantation society crumbled beneath Union boots.

This romanticized version perpetuated devastating myths—that Sherman burned Atlanta to the ground (he didn't; Confederate forces destroyed much of it themselves), and that enslaved people were merely passive victims swept along by military tides.

"It's the moment where ideas of American freedom came into collision," Parten observes, recognizing that our national reckoning with this period remains incomplete.

The popular narrative reduces 400,000 enslaved Georgians to background figures, their agency erased, their voices silenced. But what if we've been telling the story backwards?

The Real Protagonists Emerge

Parten's revolutionary approach places formerly enslaved people at the center of the narrative, revealing Sherman's march as something unprecedented: a mass liberation movement orchestrated not by Union generals, but by the enslaved themselves.

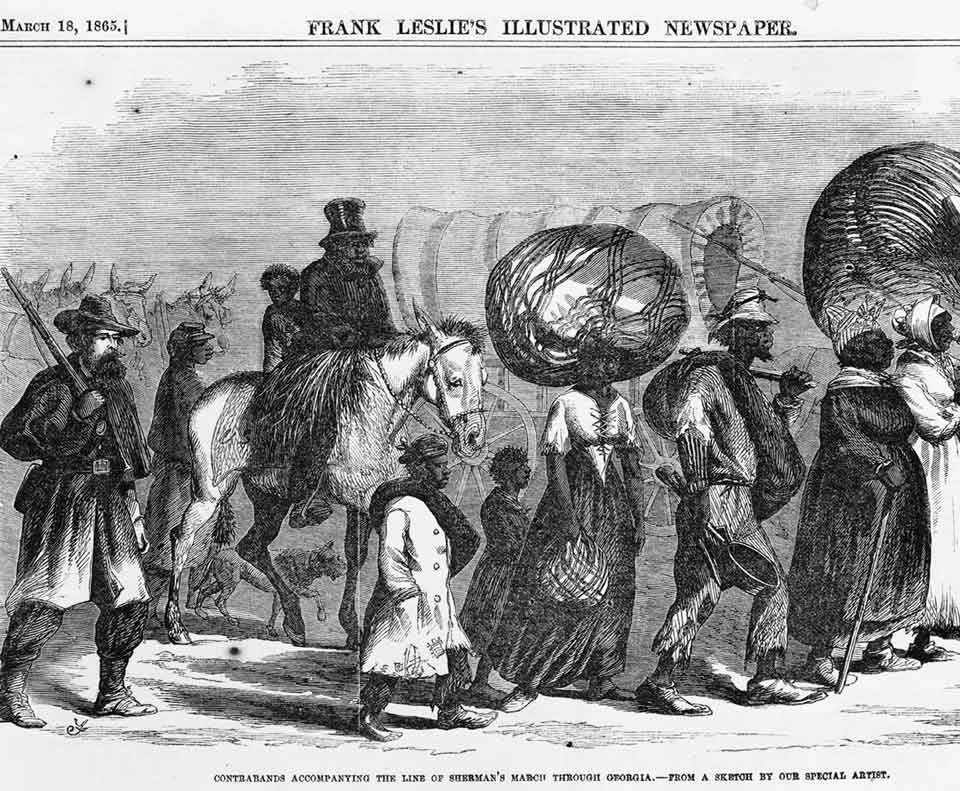

As Sherman's forces carved their path of destruction toward Savannah, they were joined by waves of self-emancipating people who "fled plantations and rushed into the army's path."

The scale was staggering. Soldiers described the movement as "practically providential." The enslaved themselves saw divine intervention, hailing Union troops as "angels of the Lord" and celebrating their arrival "as if God himself had ordained the war and the days of Revelation had arrived."

This was no passive exodus. These were strategic actors who understood the moment's potential and seized it with remarkable coordination.

They served as scouts, intelligence agents, and guides, actively shaping military outcomes while Sherman's forces advanced through hostile territory. "Enslaved people were agents of their own story," Parten emphasizes, and their contributions proved "paramount" to Union victory.

Jubilee: The Spiritual Revolution

Jubilee: The Spiritual Revolution

The religious dimension of this movement reveals its deeper significance. Enslaved people understood their liberation through the biblical concept of jubilee—that sacred time when debts were forgiven, captives freed, and society renewed in justice.

This wasn't merely escape; it was apocalyptic transformation.

"It has all these competing, different elements, but fundamentally what's at the bottom of it is this really radical idea of society renewing itself in a way that is rooted to equity and justice," Parten explains.

When enslaved people claimed jubilee, they weren't just seeking personal freedom—they were demanding the moral regeneration of America itself.

The camps they created while following Sherman's forces became spaces of extraordinary social experimentation.

Families like Sally and her husband Ben used the chaos of war to reconstruct bonds shattered by slavery's violence.

Others learned to read, practiced democracy, and imagined new forms of community. These "refugee camps," as Parten terms them, housed people who had risked everything on an uncertain future.

The Unwelcome Liberation

Yet even within Sherman's army, racism constrained the liberation movement. Many Union commanders viewed the mass of followers as a burden, attempting to prevent them from staying with the forces.

The formerly enslaved endured brutal conditions—sleeping in the open, marching up to 20 miles daily, often without adequate food or shelter.

Some died from exposure and disease. Union soldiers frequently displayed the same racial prejudices as their Confederate enemies.

Sherman himself had complex and often contradictory views on race and slavery. While he prosecuted the war with devastating effectiveness, he was no abolitionist crusader.

His primary concern was military victory, not racial justice. Yet the enslaved people who followed his army transformed his campaign of destruction into something he never intended: a liberation movement that would reshape American society.

Despite this hostility, the self-emancipated persisted. Their collective determination created what Parten calls a "refugee crisis"—20,000 people whose very presence forced the government to acknowledge them and develop new policies.

By the time Sherman reached Savannah on December 21, 1864, the refugee population equaled the city's size.

Finding Voice in the Room of Power

Perhaps the most remarkable moment came when Sherman met with Black religious leaders in Savannah.

Speaking through Garrison Frazier, the refugees found their voice in rooms of power they had never been permitted to enter.

Though not physically present, their collective weight and movement had earned them representation before Sherman and Secretary of War Edwin Stanton—two of the nation's most powerful men.

"They're not [physically] in the room, but they're nonetheless really doing things to change the policy of the army, the US government," Parten notes.

This was democracy in its rawest form—people without votes wielding influence through sheer moral force and strategic action.

Redefining American Freedom

Parten's scholarship arrives at a crucial moment when Americans are reassessing their understanding of freedom, democracy, and historical truth.

His work demonstrates how centering marginalized voices doesn't diminish historical complexity—it enriches it immeasurably.

"We can include others in this dynamic as well—the war becomes so much more multidimensional, it becomes so much more local, so much more personalized," he argues.

Rather than the simplified narrative of North versus South, we discover a nuanced story of multiple actors pursuing different visions of American possibility.

The implications extend beyond academic history. If enslaved people could orchestrate their own liberation amid the chaos of Sherman's total war, what does that suggest about agency, resistance, and the ongoing struggle for justice? Sally's nightly searches through Union camps weren't just personal quests—they represented the broader American journey toward a more perfect union.

The March Continues

"Somewhere Toward Freedom" challenges readers to abandon comfortable myths about American freedom and confront more complex truths. Sherman's march wasn't just military strategy or Southern destruction—it was the moment

when America's most oppressed population seized control of their destiny and reshaped the nation's future.

In our current moment of national reckoning, Parten's work offers both inspiration and instruction.

The formerly enslaved who followed Sherman understood that freedom isn't granted—it's claimed, step by difficult step, through collective action and unwavering faith in human dignity.

Their march toward freedom continues in every generation that refuses to accept inherited limitations on human possibility.

Sally may have searched those camps for her children, but she was really searching for America's soul.

-30-