T&T | Colonial Ships Return: Trinidad's Coat of Arms Reversal Signals Sovereignty Retreat

Persad-Bissessar administration restores Columbus vessels, exiles steelpan from national symbol until 2031

PORT-OF-SPAIN, Trinidad and Tobago, December 23, 2025 - The ships are back. The Pinta, the Nina, and the Santa Maria—Christopher Columbus's instruments of Caribbean conquest—have been quietly restored to Trinidad and Tobago's coat of arms, replacing the steelpan that briefly symbolized the nation's post-colonial cultural identity.

Prime Minister Kamla Persad-Bissessar's administration has not merely deferred national symbol reform; it has actively reversed it, re-centering Trinidad's official identity on European imperial heritage rather than indigenous Caribbean creativity.

The decision represents more than aesthetic preference. It is a deliberate choice about whose Trinidad and Tobago appears on government letterhead, currency, and official seals for the next six years—minimum.

Minister of Homeland Security Roger Alexander has described the Government’s decision to extend the time allowed for the use of the former coat of arms until 2031 as a cost-saving measure.

He said so while sharply criticising the Opposition for what he said was an attempt to play the race card to gain political relevance.

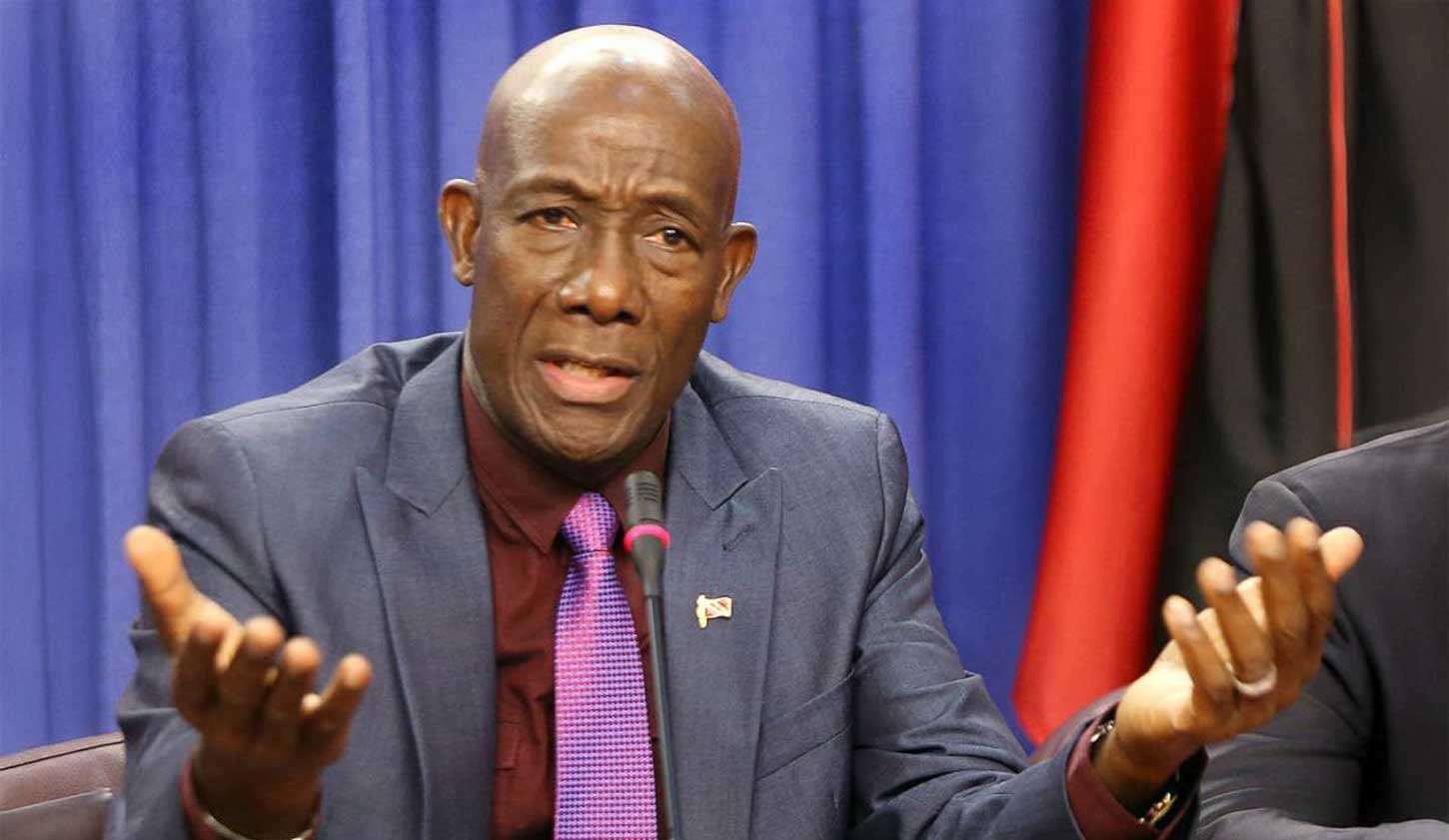

Prime Minister Kamla Persad-BissessarThe Vision That Was

Prime Minister Kamla Persad-BissessarThe Vision That Was

When Keith Rowley announced the coat of arms redesign in September 2024 to a standing ovation at the People's National Movement convention, the symbolism was unmistakable.

The steelpan—Trinidad's gift to world music, born from the ingenuity of marginalized communities transforming discarded oil drums into sophisticated instruments—would replace the vessels that brought enslavement, disease, and colonial domination to Caribbean shores.

"That should signal that we are on our way to removing the colonial vestiges that we have in our constitution," Rowley declared, articulating a vision shared by the broader Caribbean decolonization movement.

Rowley stated there would be no complete overhaul or immediate replacement of the old coat of arms—but, rather a gradual transition, acknowledging public concern about the high costs associated with such a change.

The former People’s National Movement (PNM) administration introduced a new coat of arms featuring the pan shortly before demitting office.

St. Lucia had already abandoned the UK Privy Council for the Caribbean Court of Justice in 2023. Rowley himself advocated ending Trinidad's status as "squatters on the steps of the privy council." The coat of arms change aligned with regional momentum toward self-definition.

The steelpan represented something Trinidad created, something the world recognized as uniquely Trinidadian genius. The Columbus ships represented what was done to Trinidad—the beginning of centuries during which the island existed to serve European commercial interests.

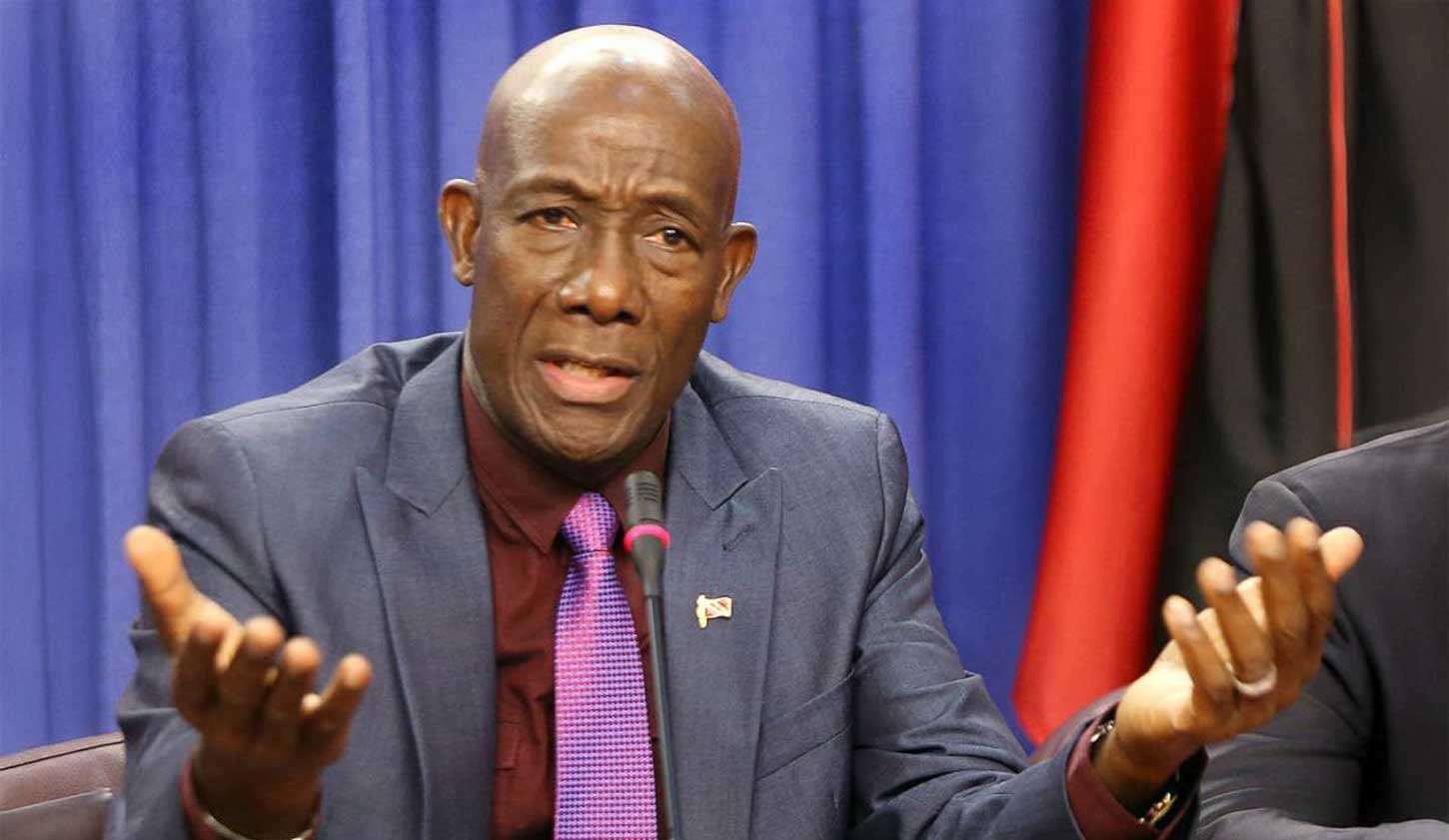

Former Prime Minister Dr. Keith RowleyWhat the Ships Mean

Former Prime Minister Dr. Keith RowleyWhat the Ships Mean

These are not decorative galleons on a maritime fantasy. The Pinta, Nina, and Santa Maria carried the architects of Caribbean genocide. They opened sea routes that would transport millions of enslaved Africans across the Middle Passage.

They symbolize the imperial trade networks that extracted Caribbean wealth to build European capitals. Every time a Trinidadian child looks at their passport or sees the national coat of arms, they now encounter these vessels of conquest as defining national symbols.

The irony cuts deep: Trinidad and Tobago is among 14 Caribbean nations actively seeking reparations from Britain and other colonial powers for the damages of slavery and colonization. Yet the current administration has chosen to enshrine the very ships that initiated that exploitation as central to national identity—at least until 2031, when the redesign freeze supposedly lifts.

The Sovereignty Signal

By restoring imperial imagery and deferring reform for half a decade, the Persad-Bissessar government sends an unambiguous message about its conception of Trinidadian identity. A coat of arms is not incidental symbolism; it declares who a country believes itself to be. This decision places that identity squarely under the shadow of empire.

While regional neighbors advance decolonization—rejecting the Privy Council, redesigning flags, removing colonial statues—Trinidad retreats. The steelpan, which required no European instruction or permission to create, has been exiled from the national symbol in favor of ships that required Caribbean subjugation to matter.

The 2031 Question

Six years is not a short deferral. Children entering primary school in 2026 will complete their entire elementary education under these restored colonial symbols. A generation of Trinidadians will grow up with the Columbus ships defining their national identity, the steelpan relegated to cultural festivals rather than constitutional significance.

The question Persad-Bissessar's administration has not answered: If not the steelpan—an instrument of resilience, creativity, and global cultural influence—then what symbol better represents post-independence Trinidad? Or is the answer implicit in the restoration itself—that colonial inheritance remains the preferred foundation for national identity?

The ships have returned to Trinidad's coat of arms. Under whose masts will the Trinidad Government sail?

-30-