JAMAICA | Sidelined by Design: Why Jamaica's Local Authorities Were Helpless When Hurricane Melissa Hit

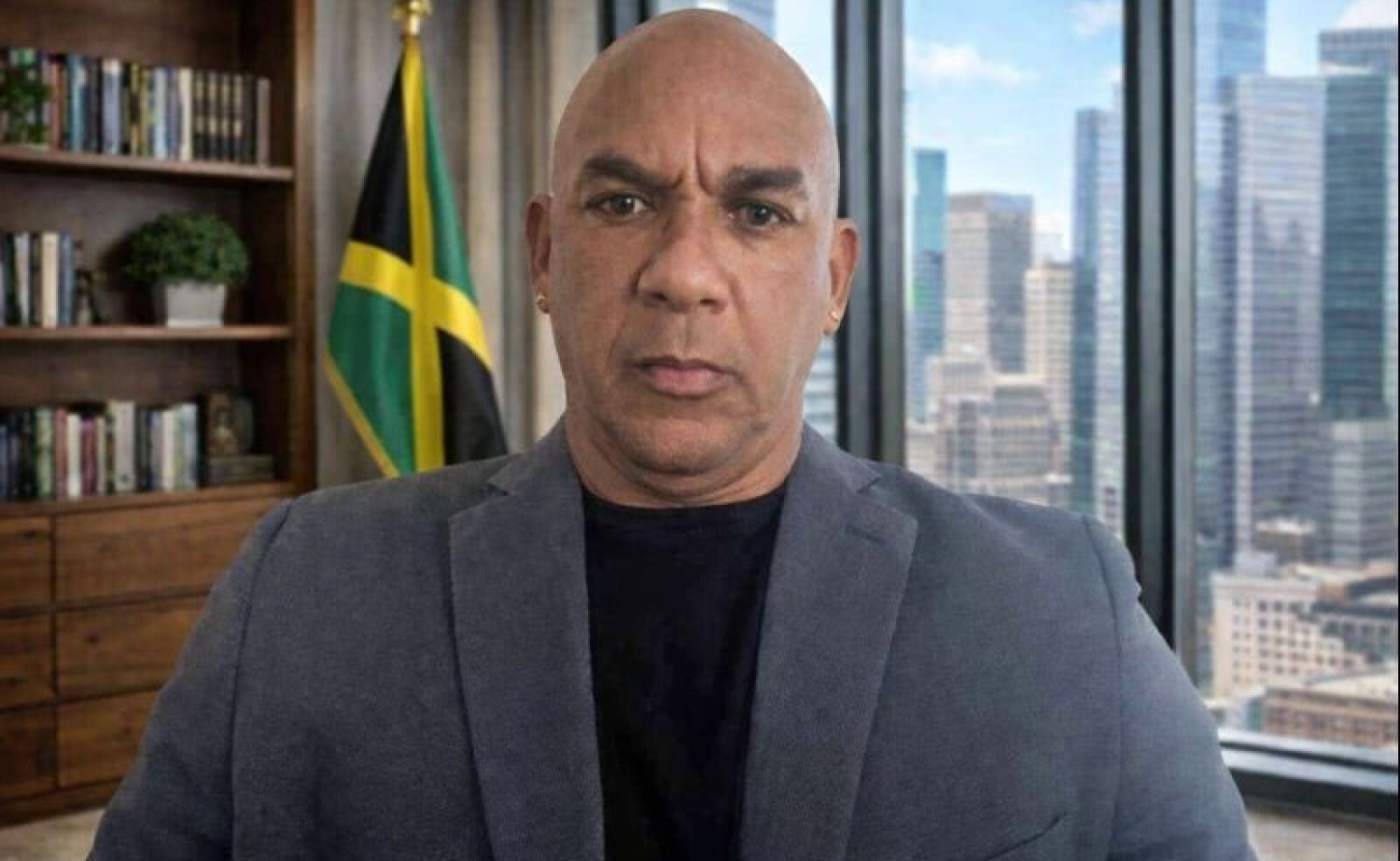

The laws exist. The mandate is clear. So why were our parishes reduced to spectators in their own crisis? Christopher Powell Explains

MONTEGO BAY, Jamaica, January 20, 2026 — The devastation wrought by Hurricane Melissa has exposed something far more troubling than damaged infrastructure and displaced families.

It has laid bare a profound and dangerous disconnect at the heart of our national disaster response: the agencies legally mandated to lead local preparedness—our parish authorities—were reduced to passive spectators, watching from the sidelines as a centralised command structure attempted to solve deeply localised problems from Kingston.

This is not merely an operational hiccup. It is a systemic failure that contravenes established law and jeopardises the resilience of communities across this island.

The statutory role of local authorities is unambiguous. The Local Governance Act of 2016, Section 21(1)(f), explicitly charges them to "engage in disaster preparation, mitigation and recovery as well as emergency management and responses, within the area of its jurisdiction."

The Disaster Risk Management Act of 2015 reinforces this mandate, making each local authority responsible for the full disaster management cycle—prevention, mitigation, preparation, response, and recovery—within its parish.

The legal architecture for a robust, decentralised system is firmly in place. On paper, Jamaica has everything it needs.

Yet in practice, this architecture remains an empty shell.

Responsibility Without Resources

The central question is why this legislative intent has been so thoroughly neutered. The answer lies in chronic and deliberate deprivation of capacity. Local authorities have been handed monumental responsibility without the corresponding tools, resources, or institutional support to fulfil it.

Consider the typical parish configuration: a single, isolated Disaster Coordinator with no departmental staff, limited training, and only a small storeroom stocked with basic supplies.

This individual, however dedicated, is set up to fail. When crisis strikes, the inevitable result is reliance on central government agencies that lack the granular community knowledge essential for effective response.

This capacity gap is further illustrated by missed opportunities for advancement. In 2021, the Caribbean Disaster Emergency Management Agency (CDEMA), through its BRICS Programme, offered direct funding to local authorities to develop critical Parish Disaster Plans.

This was precisely the kind of external support that could have built genuine capacity at the parish level.

The result? Only the St. Thomas Municipal Corporation attempted to access this vital resource—and its efforts were stymied by a lack of support from its parent Ministry.

This episode reveals a deeper pathology: not only are local authorities chronically under-resourced, but existing pathways to build capacity are actively blocked by bureaucratic inertia at higher levels.

One must ask whether this neglect is mere incompetence or something more deliberate—a centralised government reluctant to cede operational control to parish authorities, even when the law demands it.

Beyond Melissa: The Stakes of Inaction

The implications extend far beyond hurricane response. Climate change is intensifying threats with each passing year.

Unchecked development continues to place communities in vulnerable locations. Environmental degradation erodes natural buffers that once provided protection.

If successive governments are sincere in their commitments to the UN Sustainable Development Goals and our own Vision 2030, then a fundamental recalibration of governance is urgently required.

Disaster resilience cannot remain an afterthought, managed reactively from the capital. It must be woven into the very fabric of local land-use and development decisions—decisions that only empowered parish authorities can make effectively.

A Path Forward

Transforming local authorities from sidelined spectators into empowered leaders of community resilience requires concrete action, not more paper mandates.

Parish Development Orders and Land Use Maps must become binding documents that guide Planning Committee decisions, directing development away from high-risk zones.

These committees must be legally required to consider risk assessments from Parish Disaster Coordinators before approving any project. Central government must actively facilitate—not obstruct—local authorities in accessing external funding from agencies like CDEMA.

Most critically, each local authority must establish a fully funded and staffed Disaster Management Unit. The current model—one overwhelmed coordinator with a storeroom—is a recipe for failure.

We need dedicated teams with expertise in logistics, communication, and community outreach. We need continuous, mandatory training programmes that create a culture of preparedness rather than reaction.

Financial institutions granted six-month mortgage moratoriums after Melissa. These relief measures will expire long before many affected communities fully recover. Coordination between ministries and lending institutions must align relief timelines with reality on the ground.

Hurricane Melissa is Not an Anomaly

It is a precursor. The current centralised, reactive model of disaster management is inefficient, unsustainable, and—as Melissa demonstrated—incapable of meeting the challenge.

The laws of this nation wisely vest primary responsibility for local disaster resilience in local authorities. It is now a matter of political will—and perhaps national survival—to provide them with the mandate, the means, and the ministerial support to execute that responsibility.

We must move beyond legislation to genuine empowerment. By investing in decentralised capacity, integrating risk-sensitive planning, and unlocking critical resources, we can transform our local authorities from passive observers into the first line of defence.

The time for ad-hoc recovery is over. The era of planned, localised resilience must begin.

Christopher Powell is a former Chief Executive Officer of four Municipal Corporations and an International Development Consultant.

-30-