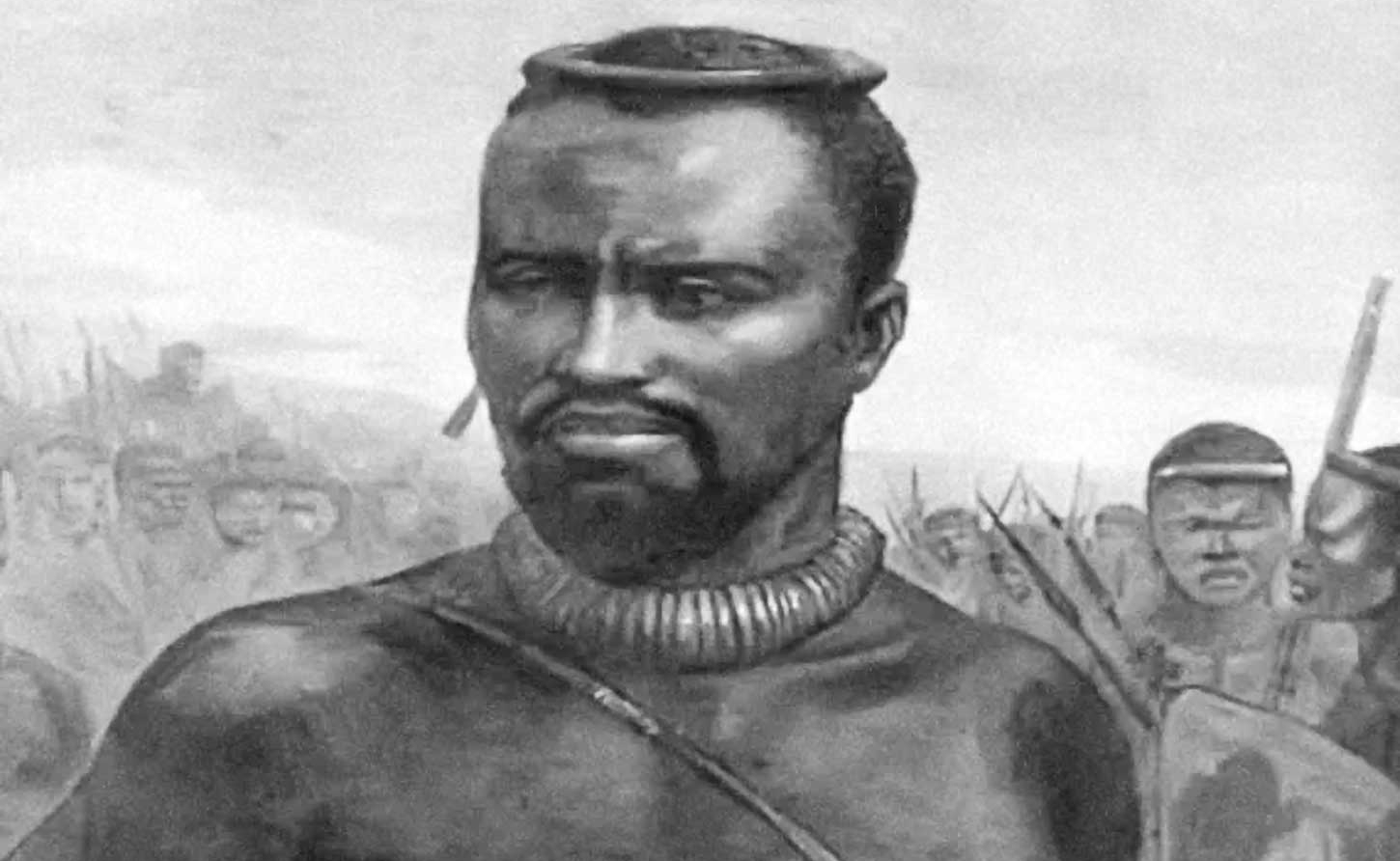

JAMAICA | Chief Takyi, the War he Led & the Anti-Slavery Actions he Inspired.

KINGSTON, Jamaica April 14, 2025 - BY Verene Shepherd & Ahmed Reid. - On April 4, a film on anti-slavery activist, Chief Takyi, enslaved on Frontier sugar plantation in Jamaica’s north-eastern parish of St. Mary, the parish in which the Ian Fleming Airport is located, was screened at the Bob Marley Museum as part of an effort by film-maker and actress, Donisha Prendergast, to publicize local films.

The film was the brainchild of Harvard Historian, Professor Vincent Brown, author of the award-winning 2022 book, Tacky’s Revolt: The Story of an Atlantic Slave War. The film sought to shed light on the man, his role in the 1760 war in Jamaica, which broke out in St. Mary, but had tentacles that spread far and wide and the aftermath and implications of the war for the Atlantic World.

The timing was chosen to coincide with the anniversary of the start of the 1760 anti-slavery war led by Chief Takyi and the annual Takyi Day. As a reminder, in 2022, the Government of Jamaica declared April 8 as “Chief Takyi” Day.

In addition there were academics like myself (in my 2005 and 2018 public lectures), Historian Richard Hart; and Professors Carolyn Cooper, Ahmed Reid, Maria Bolletino (in her 2009 Thesis, “Slavery, war, and Britain's Atlantic empire: black soldiers, sailors, and rebels in the Seven Years' War”, which examines “Tacky’s Revolt), and Vincent Brown.

Chief Takyi’s biographical details are sparse. Enoch Tacky from Ghana tells us that he was a Fante, not Akan nor Ga, as Richard Hart and others thought previously. As we understand it, the Fante are people of the southern coast of Ghana between Accra and Sekondi-Takoradi.

They speak a dialect of Akan, a language of the Kwa branch of the Niger-Congo language family. Takyi was captured and sold into chattel slavery in Jamaica and located on Frontier Plantation.

In St. Mary, not only is there a monument to honour Chief Takyi, but a school and a waterfall have been named after him. The monument in his honour stands defiant in a location that was once unwelcome to Black people: right in front of the court house, the symbol of oppression; beside the Anglican church that was the planters’ church; right in the churchyard burial site for the elite. In fact, the monument is located in sight of the tomb of the white planter, Charles Price.

Against all odds, based on the level of colonial oppression in the island, Takyi, assisted by three other headmen, including Chief Jamaica, (about which more needs to be known) fought for freedom from enslavement.

The enslaved warriors raided Fort Haldane for weapons, drumming up support from plantations like Esher, Ballards Valley, Trinity, Heywood Hall and others.

Indeed, they had to fight against the British military out in the open because the war escalated so quickly that Takyi and his supporters barely had enough time to conceal themselves within the tradition of guerilla warfare.

“ By what standard of morality can the violence used by a slave to break his chains be considered the same as the violence of the slavemaster? - Walter Rodney ”

Above all, they had to skillfully negotiate with the Maroons so they would not all fight against the rebel army. Maroon griots, through oral history (which should not be discounted in favour of pro-slavery colonial writers), tell us that some Maroons only pretended to fight and pursue the rebels into the woods; that they even returned with a collection of human ears, which they pretended to have cut off from the rebels they had slain in battle, instead of those who were already dead.

And, according to Hart’s 1985 work, Slaves who Abolished Slavery, (Volume 2), they duly collected their reward too! It took the declaration of Martial Law (10-21 April) and the cordoning off of the parish by various companies of British troops to prevent the war from spreading further and becoming an island-wide revolution.

While the number of casualties on each side will never be known with any certainty, we know the war took a heavy toll on Takyi’s anti-slavery warriors, many of whom were killed in battle.

Oral History claims that Takyi escaped behind the falls, but most written accounts claim he was killed by Davy. Others are said to have chosen suicide rather than surrender, some had to face execution by judicial order and still others were deported, some to the Bay of Honduras.

But Takyi and his troops also took out quite a few of the oppressors. Governor Moore is thought to have under-reported the number of white casualties, admitting to just 16; but a high of 40-60 was reported by contemporary writers.

Above all, Chief Takyi inspired others to carry on the fight way beyond 1760. No sooner had martial law been lifted in St. Mary in mid-1760 than reports began to circulate once more of a protest in the parish as well as in St Thomas in the East; for there were still enslaved people in the areas in which the war had been crushed in whom the fire of protest burned fiercely enough to inspire them to undertake another attack.

After the colonial authorities discovered and quelled the St. Mary and St. Thomas in the East plots, a major protest led by Damon and involving 1000 activists broke out in Westmoreland - on ‘Whitsun Sunday’ to be specific.

Twelve whites were killed. Colonial Office Records consulted indicate that Martial Law had to be proclaimed again on 3rd June 1760 and was still in force in July 1760. Troops had to be speedily dispatched to Westmoreland as well as to St Elizabeth, Hanover and St James. Protest also erupted around this time in the parishes of St Dorothy, St Johns, St. Thomas in the East again, this time led by Kofi, and Clarendon.

It was around this time that Queen Cubah of Kingston was deported to Cuba for her role in the Kingston protests. She found herself back in Jamaica- in Hanover- where she was caught and hanged. Not until August could the English discontinue martial law; and even then, this was later said to have been too optimistic as skirmishes continued down to November.

Undeterred by the brutal punishments of any who were caught protesting and fighting, and with a plan to court Maroon support, the enslaved from 17 plantations in St Mary, including Whitehall, Frontier, Oxford and Tremolesworth, frightened white society again in 1765 in a war led by Blackwall, a ringleader in the war who had cleverly escaped punishment.

As in 1760, the main instigators were the so-called “Coromantee” headmen (A Ghanaian, Enoch Tacky, told us that this designation is incorrect); and the signal fire started on 29th November on Whitehall estate.

The whites from Whitehall were forced to flee, facilitating the enslaved in obtaining arms. Signal fires were lit on other plantations and the anti-slavery activists marched to Ballards Valley. Whites at Ballards Valley had barricaded themselves into the “Great House”, but, in an effort to smoke them out, one of the main leaders attempted to set fire to the roof.

A white man from inside apparently spotted him doing so and fired at him, killing him. It is said that he fell on those below who were thrown into disarray as he was their leader. Whites took advantage of this confusion and ran out fully armed.

This effectively crushed the protest involving leaders like Quamin and Blackwall. When it was all over, 13 enslaved men had been executed and 33 deported.

Still, enslaved people never gave up. Wars of liberation broke out again in Westmoreland in 1766 and 1777 involving 33-45 Africans, in which 19 whites were killed and 33 blacks executed.

Protest continued into the 1790s, spurred on by news of the revolution of enslaved people in Ayiti (Haiti). In fact, between 1792 and 1796, about 93 enslaved people considered dangerous were deported.

The Second Maroon war broke out in 1796, followed by other instances of protest: in 1799 after which 1000 enslaved were deported; 1803 in Kingston during which two enslaved men were executed; 1806 in St George in which one enslaved was executed and five deported; 1808 and 1809 in Kingston; 1815 in St Elizabeth led by enslaved Ibos, during which the leader was hanged at Black River

The stepped-up anti-slavery campaign in Britain in 1823 was also met in the island and region with even more intense freedom struggles. In fact, in that same year, a major war erupted in St Mary.

“ As in previous wars, Haitians were said to have been involved in many of these 1820s wars; and those suspected of being ringleaders were deported ”

At a trial of enslaved people held in December 1823, William, enslaved to Mr. Andrew Roberts of Port Maria, revealed that his father, James Sterling, who worked on Frontier estate, told him that there had been a plot afoot “to rise at the fall of Christmas 1823, and desired him to keep out of the way for fear of [him] being hurt, as it was the intention of the Negroes to begin to burn and destroy the houses, trash houses and estates; and when such fires took place, to murder all the inhabitants.”

He reported that on two occasions, on going to see his father, he had noticed “the Negroes assembled in large bodies near a bridge between Frontier estate and Port Maria, where he heard them speak of an intended rising and at that time they were flourishing their cutlasses, declaring that they would destroy all the white people”.

Unfortunately, inadvertently, this young boy betrayed the plot. On 15th December, in conversation with his master, he told him that he would have a bad Christmas and that if he wished to be safe it would be necessary for him to go on board ship as it would be useless for him to go either to the Fort [Haldane] or to any other house.

Pressed to give the names of the ringleaders, he said he could only recall the following: Charles Brown, Richard Cosley, Morrice Henry, James Sterling, Rodney Wellington, (a cooper and former head driver on Frontier) and William Montgomery.

Two other enslaved men, Ned and Douglass belonging to Mr. James Walker, were interrogated on Williams’ admitting that he saw them at one of the two meetings described above. Out of their trial came a confirmation of the plot to plan a parish-wide revolt on 18th December 1823.

The first part of the plan was to burn Frontier’s trash house and sugar works and to murder whites when they came to quench the fire. After that, they were supposed to begin at the top or east of the bay and set fire to the buildings, when a general massacre was to take place.

Williams’ warning, plus reports of suspicious goings on among the enslaved at Tremolesworth and Nonsuch, set back the plans and led to the calling out of the troops and the militarization of the parish from 16th December. Colonel Cox called out the Grenadiers, the Light Infantry, the Port Maria regiment, the Rio Nova and Bagnalls company, the Leeward Browns, the Oracabessa Company, the 3rd Battalion or Cross, the Jack’s Bay company, the Windward Browns [“Coloured” regiment].

The captains at Fort Haldane were pressed into giving Marshal Hendricks “every assistance in their power in making up the ball cartridges,” a Troopers’ Guard was ordered stationed at Frontier and Gayle’s plantations and the Black Company was ordered to mount guard duty at the court house “and remain until further order”. A detachment of troops from Stony Hill was also requested to be sent to Fort Haldane, especially after rumours came of a new outbreak on Oxford plantation.

This freedom struggle also led to trials and searches of the houses of the enslaved and ultimately to brutal punishment. Henry Cox, Colonel of the St Mary Regiment admitted in a letter to W. Bullock dated 20th December 1823: “I have taken up, and issued orders for the capture of every Negro against whom there is the least suspicion and shall proceed to try all or any of them as soon as I think that I have enough evidence to convict them.”

The main leaders, or those thought to be, were tried and punished brutally, among those hanged being Charles Brown, Richard Cosley, Morrice Henry, William Montgomery, Henry Nibbs, James Sterling, Charles Watson and Rodney Wellington.

All these hangings took place on Christmas Eve 1823. Colonel Cox reported that the hangings had taken place “with all due solemnity and decorum, attended by the custos and several magistrates, four companies of the St Mary regiment and a troop of horse”. That “only one of the wretches confessed to the Rev Mr. Girod that it was their intention to have burnt Frontier Works and Port Maria and killed the whites; but none would mention any other Negroes concerned with them or show any symptoms of religion or repentance.

They all declared they would die like men and met their fate with perfect indifference; and one laughed at the clergyman Mr. Cook when he attempted to exhort him under the gallows”. In all, 400 enslaved people were executed and 600 deported to the Bay of Honduras, a much higher casualty rate than in the 1831/32 Emancipation War.

Even so, plotting and resistance never stopped. St James experienced unrest from October 1823, based on reports coming from Kensington and other plantations. All reports indicated that the enslaved in St James were aware of the anti-slavery movement in England, drank to Wilberforce’s health and fully expected to get the news of their freedom soon. Plans were afoot in St James to rebel in December 1823 if “free paper did not come” before then. The plot was discovered and the ringleaders deported.

Red Background“ Chief Takyi inspired others to carry on the fight way beyond 1760. No sooner had martial law been lifted in St. Mary in mid-1760…. The fight erupted in St Thomas in the East and enslaved people in the areas in which the war had been crushed in whom the fire of protest burned fiercely enough to inspire them to undertake another attack. ”

In a Dispatch from the Duke of Manchester, Governor of Jamaica, to the Earl of Bathurst dated 16th June 1824, apparently, shortly after, news came from St George in January of that year that plans were afoot – on a larger scale than in St Mary in 1760, 1765 and 1823- for a rebellion. In that same year came news of the Argyle war in Hanover in which Richard Hemmings [“free coloured”]; and Richard Hanson were believed to have played a significant part.

As in previous wars, Haitians were said to have been involved in many of these 1820s wars; and those suspected of being ringleaders were deported. Interestingly also – and significant for how we have been taught to view the Maroons, in the 1824 Hanover war, A. Campbell of the Western Interior Regiment informed William Bullock that from reports he obtained, “It appears that the Maroons of Accompong Town are the instigators of this Rebellion and that the slaves of this vicinity are acting only a secondary part”.

Based on all we now know of the magnitude of the war led by Chief Takyi and the heavy price he and his warriors paid in the cause of Jamaica’s freedom from chattel enslavement, it is time for a grateful nation to overturn the negative recommendation of the majority of members of the Committee appointed in October 2007 by former Prime Minister, Bruce Golding, to review the system of National Honours and Awards, that Chief “Tacky” (along with Ms Lou and Bob Marley) should not be elevated to the status of National Hero.

Afterall, he meets all the criteria that the Committee approved: “an individual who has made outstanding contribution to the struggle against conquest, slavery and colonialism, for the creation of a Jamaican nation and/or subsequent development along an anti-neocolonial path”. The Committee did indicate that the issue could be considered again the future.

In the case of Takyi, the recommendation was that ‘a researcher be identified to write a paper justifying Tacky’s elevation to the status of National Hero for future consideration as the Committee did not have such a paper to guide it at this time.’ There was abundant evidence then, there is abundant evidence now.’ Let’s go!!

-30-